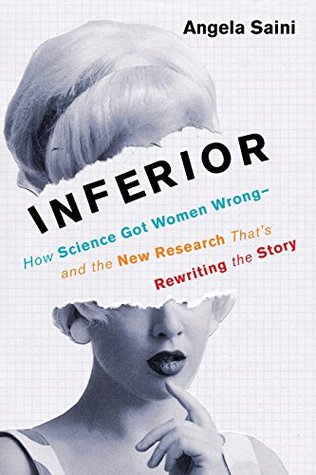

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Angela Saini

Read between

January 10 - January 12, 2021

Statistics collected by the Women’s Engineering Society in 2016 show that only 9 percent of the engineering workforce in the United Kingdom is female and just over 15 percent of engineering undergraduates are women.

According to the Women’s Engineering Society, there’s little gender difference in enrollment and achievement in the core science and math subjects at secondary level in UK schools. In fact, girls are now more likely than boys to get the highest grades in these subjects. In the United States, women have earned around half of all undergraduate science and engineering degrees since as far back as the late 1990s.

A couple of years after I graduated from university, in January 2005, the president of Harvard University, economist Lawrence Summers, gave voice to one controversial explanation for this gap. At a private conference he suggested that “the unfortunate truth” behind why there are so few top women scientists at elite universities might in some part have to do with “issues of intrinsic aptitude,” that a biological difference exists between women and men.

Our relationships are guided by the notion, fed by many decades of scientific research, that men are more promiscuous and women are monogamous. Even our visions of the past are loaded with these myths.

If biological differences exist, we can’t help but want to know. More than that, if we want to build a fairer society, we need to be able to understand these gaps and accommodate them. The problem is that answers in science aren’t everything they seem.

Women are so grossly underrepresented in modern science because, for most of history, they were treated as intellectual inferiors and deliberately excluded from it. It should come as no surprise, then, that this same scientific establishment has also painted a distorted picture of the female sex.

UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, which keeps global figures on women in science, estimates that in 2013 just a little more than a quarter of all researchers in the world were women. In North America and Western Europe, female researchers were 32 percent of the population. In Ethiopia, the proportion of female researchers was only 13 percent.

When researchers Mary Ann Mason, Nicholas Wolfinger, and Marc Goulden published a book on this subject in 2013, titled Do Babies Matter: Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower, they found that married mothers of young children in the United States were a third less likely to receive tenure-track jobs than married fathers of young children.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics runs an annual Time Use Survey to pick apart how people spend their hours. Women now make up almost half the labor force, yet in 2014 the bureau found that women spent about half an hour more every day than men doing household work.

In households with children under the age of six, men spent less than half as much time as women taking physical care of these children. At work, on the other hand, men spent fifty-two minutes a day longer on the job than women did.

A man who’s able to commit more time to the office or laboratory is naturally more likely to do better in his career than a woman who can’t. When decisions are made over who should take maternity or paternity leave, it’s also almost always mothers who take time out.

Small individual choices, multiplied over millions of households, can have an enormous impact on how society looks.

Housework and motherhood aren’t the only things affecting gender balance. There’s outright sexism, too. In a study published in 2012, psychologist Corinne Moss-Racusin and a team of researchers at Yale University explored the possibility of gender bias in recruitment by sending out fake job applications for a vacancy of laboratory manager. Every application was identical except that half were given a female name and half a male name. When they were asked to comment on these potential employees, scientists rated women significantly lower in competence and hireability.

Another study, published in 2016 in the world’s largest scientific journal, PLOS ONE, looked at how male biology students rated their female counterparts. Cultural anthropologist Dan Grunspan, biologist Sarah Eddy, and their colleagues asked hundreds of undergraduates at the University of Washington what they thought about how well others in their class were performing. “Results reveal that males are more likely than females to be named by peers as being knowledgeable about the course content,” they wrote.

Male grades were overestimated—by men—by 0.57 points on a four-point grade scale.

The year before, PLOS ONE had been forced to apologize after one of its own peer reviewers suggested that two female evolutionary geneticists who had authored a paper should add one or two male coauthors. The pa...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Another problem in parts of the sciences, the extent of which is only now being laid bare, is sexual harassment. In 2015 virus researcher Michael Katze was banned from entering the laboratory he headed at the University of Washington following a string of serious complaints, which included the sexual harassment of at least two employees. BuzzFeed News (which Katze tried to sue to block the release of documents) ran a lengthy account of the subsequent investigation, revealing that he had hired one employee “on the implicit condition that she submit to his sexual demands.”

So here, in all the statistics on housework, pregnancy, child care, gender bias, and harassment, we have some explanations for why so few women are at the top in science and engineering. Rather than falling into Lawrence Summers’s tantalizing trap of assuming the world looks this way because it’s the natural order of things, take a step back. Imbalance in the sciences is at least partly because women face a web of pressures throughout their lives, which men often don’t face.

In certain subjects, women tend to outnumber men both at the university level and in the workplace. There are usually more women than men studying the life sciences and psychology. And in some regions, women are much better represented in science overall, showing that culture is also at play. In Bolivia, women account for 63 percent of all scientific researchers. In central Asia they are almost half. In India, where my family originate from (my dad studied engineering there), women make up a third of all students in engineering courses.

The Royal Society of London, officially founded in 1663 and one of the oldest scientific institutions still around today, failed to elect any women to full membership until 1945.

By the end of the nineteenth century, science had transformed into something more serious, with its own set of rules and official bodies. By then, women found themselves almost completely pushed out, says Miami University historian Kimberly Hamlin.

Doctors argued that the mental strains of higher education might divert energy away from a woman’s reproductive system, harming her fertility.

Cambridge would wait until 1921 to award degrees to women. Similarly, Harvard Medical School refused to admit women until 1945. The first woman applied for a place almost a century earlier.

The most famous example is Marie Curie, the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, but nevertheless denied from becoming a member of France’s Academy of Sciences in 1911 because she was a woman.

At the start of the twentieth century, American biologist Nettie Maria Stevens played a crucial part in identifying the chromosomes that determine sex, but her scientific contributions have been largely ignored by history. When mathematician Emmy Noether was put forward for a faculty position at the University of Göttingen during the First World War, one professor complained, “What will our soldiers think when they return to the university and find that they are required to learn at the feet of a woman?” Noether lectured unofficially for the next four years under a male colleague’s name and

...more

In 1944 the Austrian-born physicist Lise Meitner failed to win a Nobel Prize despite her vital contribution to the discovery of nuclear fission. Her life story is a lesson in persistence. When she was growing up, girls weren’t educated beyond the age of fourteen. Meitner was privately tutored so she could pursue her passion for physics. When she finally secured a research position at the University of Berlin, she was given a small basement room and no salary. She wasn’t allowed to climb the stairs to the levels where the male scientists worked.

Rosalind Franklin’s enormous part in decoding the structure of DNA was all but ignored when James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel after her death in 1962. And as recently as 1974 the Nobel Prize for the discovery of pulsars wasn’t given to astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who actually made the breakthrough, but to her male supervisor.

An article in the New York Times in 2013 stated that scientific journals had published thirty thousand articles on sex differences since the turn of the millennium. Be it language, relationships, ways of reasoning, parenting, physical and mental abilities, no stone has gone unturned in the forensic search for gaps.

Some scientists claim that women are on average worse than men at mathematics, spatial reasoning, and anything that requires understanding how systems, such as cars and computers, work. Others say this is because women’s brains are structurally different from men’s brains. There are also those who insist that men played the dominant part in human evolutionary history because they hunted animals, while women had the apparently less challenging role of staying at home and caring for children.

Words that sound deeply objectionable at a dinner party sound remarkably plausible when they’re falling from the mouth of someone in a lab coat. But we need to be skeptical. The study you read about in the newspaper telling you that men are better at reading maps than women, for example, may be entirely contradicted by another study on a different population of people, in which women happen to be better map readers.

Today, hidden among the barrage of questionable research on sex differences, we have a radically new way of thinking about women’s minds, bodies, and their role in evolutionary history. Fresh theories on sex difference, for example, suggest that the small gaps that have been found between the brains of women and men are statistical anomalies caused by the fact that we are all unique.

Decades of rigorous testing of girls and boys confirm that there are few psychological differences between the sexes, and that the differences seen are heavily shaped by culture, not biology.

Starting in the nineteenth century and running all the way to today, I’ve tried to find out why so much of what we think of as true is actually unreliable. I investigate the studies that have hit the headlines, claiming to show us that harmful stereotypes about women are backed by science.

She also had an interest in science. In her note to Darwin, she had one simple request. It was based on a shocking encounter she’d had at a meeting of women in Boston. Someone had taken the position of arguing that “the inferiority of women; past, present and future” was “based upon scientific principles,” Kennard writes. The authority that allowed this person to make such an outrageous statement apparently came from no less than one of Darwin’s own books.

If polite Mrs. Kennard was expecting the great scientist to reassure her that women aren’t really inferior to men, she was about to be disappointed.

In The Descent of Man he argues that males gained the advantage over females across thousands of years of evolution because of the pressure they were under to improve in order to win mates.

In evolutionary terms, he implies, females can happily reproduce no matter how dull they are because they’re the ones that give birth. They have the luxury of sitting back and choosing a mate, while males have to work hard to impress them and compete with other males for their attention.

We can guess how Caroline Kennard must have felt about Darwin’s comments from the fiery, long response she sent back. Her second letter is not nearly as neat as her first. She argues that, far from being housebound, women contribute just as much to society as men do. It was, after all, only in wealthier middle-class circles that women tended not to work.

What we do know is that she was right—his scientific ideas mirrored how society felt at the time, and this was coloring his judgment of what women were capable of doing. Darwin’s attitude belonged to a train of scientific thinking that stretched back at least as far as the Enlightenment, when the spread of reason and rationalism through Europe changed the way people thought about the human mind and body.

Another example is Darwin’s cousin, the English scientist Francis Galton, remembered by history as the father of eugenics and for his devotion to measuring the differences between people. Among his quirkier projects was a “beauty map” of Britain, produced near the end of the nineteenth century by secretly watching local women and grading them from the ugliest to the most attractive.

Being able to gauge and standardize coated what would otherwise have been seen as ridiculous enterprises with the sweet perfume of scientific respectability.

By 1887 only two-thirds of US states allowed a married woman to keep her own earnings. And it wasn’t until 1882 that married women in the United Kingdom were allowed to own and control property in their own right.

English writer Mary Wollstonecraft, who lived a century earlier, urged women to educate themselves. “Till women are more rationally educated, the progress of human virtue and improvement in knowledge must receive continual checks,” she wrote in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792.

The new and controversial science of evolutionary biology became a particular target. Antoinette Brown Blackwell, believed to be the first woman ordained by an established Protestant denomination in the United States, complained that Darwin had neglected sex and gender issues.

The area’s biggest attraction is a preserved post–Civil War house covered in pale clapboard siding. In 1894, not long after this house was built, a middle-aged schoolteacher from right here in Concord published some of the most radical ideas of her age. Her name was Eliza Burt Gamble.

We don’t know much about Gamble’s personal life, except that she was a woman who had no choice but to be independent. She had lost her father when she was two, her mother when she was around sixteen. Left without support, she made a living by teaching at local public schools. According to some reports, she went on to achieve impressive heights in her career. She also married and had three children, two of whom died before the century was out.

Gamble believed there was more to the cause than securing legal equality. One of the biggest sticking points in the fight for women’s rights, she recognized, was that society had come to believe women were built to be lesser than men. Convinced this was wrong, in 1885 she set out to find hard proof for herself. She spent a year studying the collections at the Library of Congress, scouring the books for evidence. She was driven, she wrote, “with no special object in view other than a desire for information.”

Evolutionary theory, despite what Charles Darwin had written about women, actually offered great promise to the women’s movement. It opened a door to a revolutionary new way to understand humans. “It meant a way to be modern,” says historian Kimberly Hamlin, whose 2014 book From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women’s Rights in Gilded Age America charts women’s responses to Darwin.