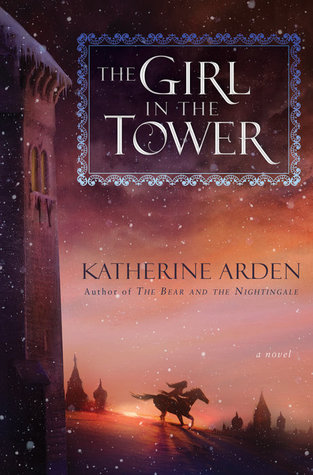

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

‘You cannot love and be immortal.’

‘You were born of winter and you will live forever. But if you touch the fire you will die.’

“But some say she died,” she said sadly. “For that is the price of loving.”

“Do you mean to stay with me now? Is that it? Be a snow-maiden in this forest that never changes?” The question was half gibe, half invitation, and full of a tender mockery.

Startled silence. Then Morozko leaned forward, elbows on knees, and said, incredulity in his voice, “You have come here, where no one has ever come without my consent, to beg a little gold for your wanderings?”

No, she might have said. It is not that. Not entirely. I was afraid when I left home, and I wanted you. You know more than I, and you have been kind to me. But she could not bring herself to say

“Many people say ‘Better to die’ until the time comes to do it,”

the stallion had lost patience, hearing the fierce anguish in her voice. He thrust his head over her shoulder and his teeth snapped a finger’s breadth from Morozko’s face. “Solovey!” Vasya cried. “What are you—?” She tried shoving him out of the way, but he would not go. I’ll bite him, the stallion said. His tail lashed his sides; one hoof scraped the wooden floor. “He’d

“There, among your own kind, that is the world for you. I left you safely bestowed with your brother, the Bear asleep, the priest fled into the forest. Could you not have been satisfied with that?” His question was almost plaintive. “No,” said Vasya. “I am going on. I will see the world beyond this forest, and I will not count the cost.” A silence. Then he laughed, softly and unwillingly. “Well done, Vasilisa Petrovna. I have never been gainsaid in my own house before.” It is high time, then, she thought, though she did not say it aloud.

What was it? Were his eyes bluer now? Some new clarity in the bones of his face? Vasya felt suddenly shy. A fresh silence fell. In the pause, all her weariness seemed to strike, as though it had waited for her to let down her guard. She leaned hard against the table to steady herself.

She went to the stove. Morozko looked round then, and a little of the remoteness left his face. She flushed suddenly. Her hair was a witchy mass, her feet bare. Perhaps he saw it, for his glance withdrew abruptly. “Nightmares?” he asked.

She thought he might be watching her, though whenever she looked, his glance was fixed on the fire.

Vasya said, “Thank you,” and the comb melted to water in her hand. She was still staring at the place where it had lain when he said, “It is little enough. Eat, Vasya.”

Solovey had already eaten his hay, with a good measure of barley, and was now edging back to the table, one eye fixed on her porridge. She began eating rapidly, to forestall him.

“You saved my life in the forest,” she said. “You offered me a dowry; you came when I asked you to rid us of the priest. Now this. What do you want of me in return, Morozko?” He seemed to hesitate, just an instant. “Think of me sometimes,” he returned. “When the snowdrops have bloomed and the snow has melted.”

This jewel had been a gift from her father, given to her by her nurse before she died. Of all Vasya’s possessions, the sapphire was her most prized.

The brush of his hand seemed to linger, raw on her skin. Vasya ignored it angrily. He was not real, after all. He was alone, unknowable, a creature of black wood and pale sky. What had he said?

“Contrary to what you believe, I do not want to come for you, dead in some hollow,” he returned coldly. A breeze, soft and bone-chilling, filtered through the room. “Will you deny me this?”

Solovey waited, neatly saddled, with an expression caught between eagerness and irritation, disliking the saddlebags on his back.

Unexpectedly, he put both hands on her fur-clad shoulders. Their eyes met. “Stay in the forest. That is safest. Avoid the dwellings of men, and keep your fires small. If you speak to anyone, say you are a boy. The world is not kind to girls alone.”

Suddenly he seemed less a man than a man-shaped confluence of shadows. There was something in his face she did not understand. She opened her mouth to speak again. “Go!” he said, and slapped Solovey’s quarters. The horse snorted and spun and they were away over the snow. 7.

“You were right,” she said bitterly. “I am dying. Have you come for me?” Morozko made a derisive noise and picked her up. His hands burned hot—not cold—even through her furs. “No,” Vasya said, pushing. “No. Go away. I am not going to die.” “Not for lack of trying,” he retorted, but she thought his face had lightened.

Vasya shrank from him. His arms tightened. “Gently, Vasya.” His voice halted her. She had never heard that note in it before, of uncalculated tenderness. “Gently,” he said again. “I will not hurt you.” He said it like a promise. She looked up at him, wide-eyed, shivering, and then she forgot fear, for with the sapphire’s glow came warmth—agonizing warmth, living warmth—and in that moment she realized just how cold she had been.

“No one can find you here,” he returned. “Do you doubt me?” She sighed. “No.” She was on the edge of sleep, warm and—safe. “Did you send the snowstorm?” A ghost of a smile flitted across his face, though she did not see. “Perhaps. Go to sleep.”

He had taken it all from her. Or had he? Was he the cause or merely the messenger? She hated him. She dreamed about him. None of it mattered. Might as well hate the sky—or desire it—and she hated that worst of all.

What could he say? Hers was a grief he would not understand, being a thing immortal. But—“I’m sorry,” he said, surprising her. She nodded, swallowed, and said, “I’m just so tired—” He nodded. “I know. But you are brave, Vasya.” He hesitated, then bent forward and gently kissed her on the mouth.

She thought of his mouth. Her skin colored and suddenly she was furious, that he would kiss her, give her gifts, and leave her without a word.

His breath slipped cool past her cheek. Goaded, she dared to do dreaming what she would not awake. She twisted her hand in his cloak and pulled him nearer. She had surprised him again. The breath hitched in his throat. His hand caught hers, but he did not untangle her fingers.

“I—you—you cannot come to me thus and go away again,” she said. “Save my life? Leave me stumbling alone with three children in the dark? Save my life again? What do you want? Do not—kiss me and leave—I don’t—” She could not find the words for what she meant, but her fingers spoke for her, digging into the sparkling fur of his robe. “You are immortal, and perhaps I seem small to you,” she said at last fiercely. “But my life is not your game.”

Sasha laughed at the image. “She is a girl,” he said. “It is different.” Sergei lifted a brow. “We are all children of God,” he said, mildly.

Where do I belong? I don’t know. I don’t know who I am. And I have eaten in your house, and nearly died in your arms, and you rode with me tonight and—I hoped you might know.”

Every time you take one path, you must live with the memory of the other: of a life left unchosen. Decide as seems best, one course or the other; each way will have its bitter

When he drew away at last, she was wide-eyed, flushed, burning. His eyes were a brilliant, perfect, flame-heart blue, and he could have been human. He let her go abruptly. “No,” he said. “I do not understand.” Her hand was at her mouth, her body trembling, wary as the girl he had once thrown across his saddlebow. “No,” he said.

He dragged a hand through his dark curls. “I did not mean—” Dawning hurt. She crossed her arms. “Did you not? Why did you come, really?”

“Is that why you brought me to your house in the forest?” Vasya whispered. “Why you fought my nightmares and gave me presents? Why you—kissed me in the dark? Because I was to be your worshipper? Your—your slave? It was all a scheme to make yourself strong?”

On swift impulse, she reached up and kissed him. “Live,” she said. “You said you loved me. Live.” She had surprised him. He stared into her eyes, old as winter, young as new-fallen snow, and then suddenly he bent his head and kissed her back. Color came into his face and color washed his eyes until they were the blue of the noonday sky. “I cannot live,” he murmured into her ear. “One cannot be alive and be immortal. But when the wind blows, and storm hangs heavy upon the world, when men die, I will be there. It is enough.”