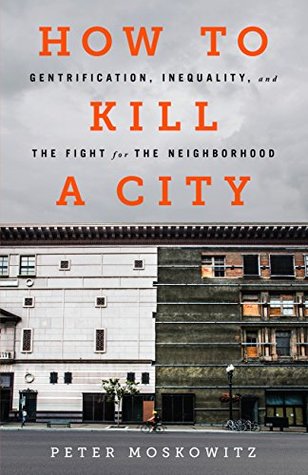

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

If land markets in the United States remain largely unregulated, or regulated in favor of higher and higher exchange values, then we can expect this process of displacement via heightened exchange value to continue ceaselessly.

The suburbs were the prototype for gentrification, not aesthetically but economically. Suburbanization was the original American experiment in using real estate to reinvigorate capitalism. Gentrification can be understood as a continuation of that experiment—suburbanization part two.

The suburbs were not built for poor people. Really, they were not built for anyone.

The 1940s were precarious times for ideological conservatives in the United States. While World War II had solved the economic problems of the Great Depression, culture and politics were in upheaval. Women were working more than ever and becoming increasingly independent of men both politically and economically. There was a brewing gay movement in many major cities, particularly San Francisco and New York. Union membership was high. The United States seemed to be heading toward liberalism. The suburbs became a way to reestablish conservative values.

The suburbs were a very particular and peculiar idea from the outset, but they were a necessary project if the United States was to maintain itself as a hypercapitalist, individualistic, patriarchal, and racist society.

The suburbs may have been inconvenient, expensive, and boring, but they were also Americans’ patriotic duty.

These subsidies to the suburbs have given us the twin illusions that the American city was in some sort of natural tailspin for decades and that the suburbs are inherently more desirable, when in reality the suburbs are just better funded.

Entire neighborhoods are becoming stash pads for the global elite who see real estate as a safer investment than the stock market.

for the first time since the era of white flight, the city’s white population is now rising faster in Manhattan than it is in the suburbs, and the black and Hispanic population is rising faster in the suburbs than it is in Manhattan.

Individuals are not responsible for gentrification, but they—we—can be complicit in it.

In the United States, housing is not considered a human right, and the ability of people to live in a given place is subject to the whims of the market. Challenging this may sound like a radical proposition, but it is radical only in the United States, in the same way universal health care is a controversial concept only here. Most other industrialized countries have realized the market will not provide for low- and middle-income people, and so their systems have made adjustments. The United States lags behind.

what we build and what we fund can have a disparate impact on different groups.

There’s also a deeper reason that will make it hard to challenge gentrification in the United States. This country was founded on displacement—on the idea that white men have a greater right to space, and even to people’s bodies, than anyone else. That’s taken the form of slavery, segregation, the genocide of Native Americans, and now, to a certain extent, gentrification. As one Bushwick activist group called Mayday says in its chants and the signs it puts up around the neighborhood, gentrification is the new colonialism.

In other words, saying hi to your neighbor really can be a radical act because it’s unprofitable, uncommodifiable.