More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

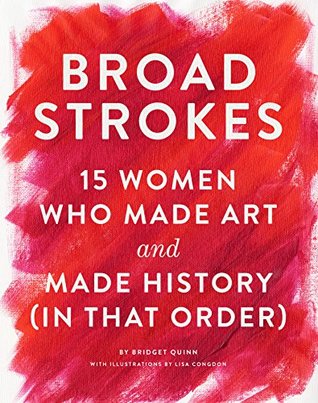

The careers of the fifteen artists that follow run the gamut from conquering fame to utter obscurity, but each of these women has a story, and work, that can scramble and even redefine how we understand art and success.

It strikes me that we might need a little caveat here before getting started. Can we agree at the outset to lay down our qualms about Ye Olde Arte Hystore at the door of this book? Put them down. Walk away. Let us agree that together we shall fear no corsets, nor nursing saviors, nor men in top hats and cravats, nor vast expanses of peachy dimpled thighs.

For the rest of Artemisia’s life, her heroines tend to this type of full-bodied but not overtly erotic women. Rather, they are heroic-size. Powerful, but in the sense of real power—physical, artistic—not sexually manipulative.

La Pittura is the Allegory of Painting, female embodiment of the art itself. Crucially, La Pittura is not a muse. She is no female goad to the (almost universally) male artist. No, La Pittura is the art of Painting itself, with all the procreative power and mystery that evokes.

It’s a radically simple canvas: the artist at work. And at the same time, Artemisia here is manifold and audacious. She is subject and object, creator and created. A deceptively uncomplicated and persuasive portrait of Painting herself, in the person of a painter and woman. By declaring that I AM SHE, Artemisia claims a position that no male artist ever can.

What I discovered as a grad student in New York was the necessary and exhausting emotion of confronting art itself. The messy, sexy, physically unnerving shock of the real. That paintings can seduce you, sicken you, haunt you.

Charlotte du Val d’Ognes is an object lesson. Like so many women, she gave up the dream of success as a professional artist when she became a wife. Her giving up is not surprising. Not just because social pressure bore down on women to put their husbands and children before all else. But it was also a terrible time to be a woman artist in France. “Although politically advanced,” notes feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, “the revolution was in many ways socially conservative.”

It’s equally true that Modersohn-Becker is mother to an alternative strand of Modernism: psychologically probing, personally brave, flagrantly and unrepentantly female. Think Frida Kahlo and Alice Neel, Ana Mendieta, Kiki Smith, Nancy Spero, Cindy Sherman, Catherine Opie, and countless more. The list is eminent and long.

Modersohn-Becker painted the first female nude self-portrait in Western history. It is true that Artemisia Gentileschi likely used her own body as the model for her Old Testament heroine in Susanna and the Elders, but that’s not the same thing. In Self-Portrait, Age 30, Modersohn-Becker is her own heroine. She is artist, subject, object, metaphor, nature, and actor.

Becker often used flowers in her portraits of women, archetypes of nature, of beauty, of femininity, but also mysterious in the way they are often held up for the viewer, a secret sign we sort of understand, the way we comprehend things in dreams.

Ever notice how no one ever talks about how Picasso wasn’t good-looking? He wasn’t. And he was short (5 ft 4 in/162 cm). Why does this never enter into accounts of his life and work? Because it doesn’t matter.

If that sounds like nonsense, maybe Hofmann’s words are clearer: “The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.” After three years of taking classes with Hofmann, uncovering the simple and the necessary, Krasner broke through—she called it a “physical break in my work”—to abstraction.

Abstract art is sometimes described as a departure from reality, but a better way to say it might be that it seeks to express a different reality.