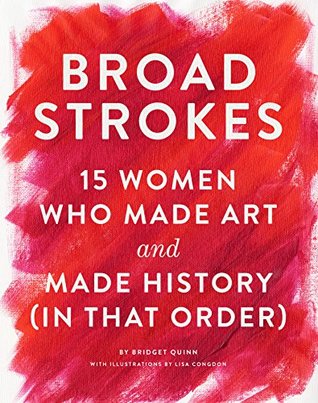

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 24 - March 29, 2018

Great lives are inspiring. Great art is life changing.

HERE IS THE FIRST THING I think you should know: Art can be dangerous, even when decorous.

chiaroscuro (bold contrasts of light and dark)

tenebrism (extremes of dominating darkness pierced by bright, insistent spotlights)

Artemisia refused the gag. And from four hundred years away she speaks to us still, saying: Dare to be great.

As Virginia Woolf famously laments in A Room of One’s Own, “For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.”

For women artists the leap from intimacy with a man to being an untalented slut has, in the public eye, never been a big one.

Bonheur: painter, horsewoman, avid hunter, lover of women, wearer of pants.

By 1850, Bonheur had received a Permission de Travestissement—cross-dressing permit—from the police. Cross-dressing (a.k.a. wearing pants) was illegal, so to evade arrest, Bonheur needed the official document. It allowed her to wear men’s clothing in public, with certain restrictions against male attire at “spectacles, balls or other public meeting places.” The permit was renewable every six months and required the signature of her doctor.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose wife Sophia was herself a painter, wrote a popular novel called The Marble Faun that treated women artists as mere copyists, doomed to tragedy. (Hawthorne had even less respect for women writers, telling his publisher, “All women as authors are feeble and tiresome. I wish they were forbidden to write on pain of having their faces deeply scarified with an oyster shell.” To which, if I might interject, the only possible response is, Screw you, Nate.)

Italy appealed to sculptors because of its abundance of marble and the great tradition of its stonecutters. Sculptors generally created a smaller-scale model that they turned over to a stonecutter who used pointing machines to accurately copy and enlarge the model into a full-size version in stone. The nearly finished work was then returned to the sculptor, who added glossy final touches.

It’s equally true that Modersohn-Becker is mother to an alternative strand of Modernism: psychologically probing, personally brave, flagrantly and unrepentantly female. Think Frida Kahlo and Alice Neel, Ana Mendieta, Kiki Smith, Nancy Spero, Cindy Sherman, Catherine Opie, and countless more. The list is eminent and long.

Modersohn-Becker painted the first female nude self-portrait in Western history. It is true that Artemisia Gentileschi likely used her own body as the model for her Old Testament heroine in Susanna and the Elders, but that’s not the same thing. In Self-Portrait, Age 30, Modersohn-Becker is her own heroine. She is artist, subject, object, metaphor, nature, and actor.

Charles Tansley used to say that, she remembered, women can’t paint, can’t write. —VIRGINIA WOOLF, TO THE LIGHTHOUSE Indeed, I am amazed, a little alarmed (for as you have the children, the fame by rights belongs to me) by your combination of pure artistic vision and brilliance of imagination. —VIRGINIA WOOLF IN A LETTER TO HER SISTER IN SOME EARLYISH MONTH OF 1912, two sisters—Vanessa Bell (née Stephen) and Virginia Stephen (soon to be Woolf)—worked together quietly indoors.

At the time of her portrait, here, Woolf was at work on her first novel, then called Melymbrosia, later published as The Voyage Out. Bell served as model for one of the novel’s main characters, Helen Ambrose. Bell would later loom large in Woolf’s masterpiece, To the Lighthouse (#2 in a BBC top 25 greatest British novels ever poll), where a painter, Lily Briscoe, is the soul of the story. Later still, Bell was Susan in Woolf’s most experimental work, The Waves (#16 in the BBC top 25).

How she ended up in a suicide ward and how she got out and how she found success at last all had the same source: “I was neurotic. Art saved me.”

I sacrificed nothing. —LEE KRASNER

“The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.”

Abstract art is sometimes described as a departure from reality, but a better way to say it might be that it seeks to express a different reality. The reality behind our visible world. Whether we’re woo-woo wingnuts or utter rationalists, I think we can all agree such reality exists. Music, for example.

What is autobiography if not selecting chunks of the past and artfully reorienting them in the present?

In my art I am the murderer. —LOUISE BOURGEOIS Art is a guaranty of sanity. —LOUISE BOURGEOIS

(Google Louise Bourgeois-peels tangerine for a gutting spectacle of how childhood pain can linger even into glorious old age).

Where is Ana Mendieta? All around us.

Some of the Instagram and Twitter posts were, predictably, lame. Too many selfies posed not in front, but behind, pointing at or goofing on the Sugar Baby’s epic-sized labia. On this point, Walker is philosophical: “I put a giant ten-foot vagina in the world and people respond to giant ten-foot vaginas in the way that they do. It’s not unexpected.” In this piece and many others, Walker is the opposite of the Internet scold. She’s saying—in effect—this life, our history, our lust and livelihoods and loves, are deeply complicated. Also, they are fucked up.

“The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that’s also what the stereotype does,” Walker said, of discovering her signature style. “So I saw the silhouette and the stereotype as linked.”

I want to go back to my eighth grade dream of being an artist. Because if I don’t do it now, then when will I??? Why delay the truth in your heart? —SUSAN O’MALLEY, AGE 24

How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. —ANNIE DILLARD, THE WRITING LIFE

“I realize that it didn’t leave a lot of room for big mistakes or wanting to admit big mistakes. But big mistakes are part of the learning process and how we grow up.”

“There is something magical about breaking the silent space between a stranger and myself. I have a theory that people are waiting to be asked and to be heard.”