More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He wasn’t large, only uncontainable.

Had he accidentally given sleep away, along with everything else?

He had given up much, but he had not yet lost his curiosity.

One could say that the sense of self is still porous in young children. That the oceanic feeling persists for some time until the scaffolding is at last removed from the walls we labor to build around ourselves under the command of an innate instinct, however touched by the sadness that comes of knowing we’ll spend the rest of our lives searching for an escape. And yet even today, I have absolutely no doubt about what I saw then.

We, too, wish to enact ourselves on the inanimate, which we want to believe we’re sovereign over. But really, it’s the unstoppable force and momentum of life that we want to control, and with which we’re locked in a struggle of wills that we can never win.

What if, I thought,

might not space also depend on us? We think we’ve conquered it with our houses and roads and cities, but what if we’re the ones who have unwittingly been made subordinate to space, to its elegant design to propagate itself infinitely through the dreams of finite beings? What if it isn’t we who move through space, but space that moves through us, spun on the loom of our minds?

Some of us are touched too much, and some too little: it is the balance that seems impossible to get right, and the lack of which unravels most relationships in the end.

If Freud were right about the uncanny stemming from something repressed that comes to light, what could be more unheimlich than returning to a place that one realizes one may never have left?

We like to think of ourselves as the inventors of monotheism, which spread like wildfire and influenced thousands of years of history. But we didn’t invent the idea of a single God; we only wrote a story of our struggle to remain true to Him and in doing so we invented ourselves. We gave ourselves a past and inscribed ourselves into the future.”

“Writers work alone,” Friedman said. “They pursue their own instincts,

The first two chapters of Genesis, taken together, are about exactly that—a meditation on creation as a set of choices, and a reflection on the consequences that result.

How many worlds did God consider before He chose to create this world?

One often hears people say that it’s easy to misunderstand. But I disagree. People don’t like to admit it, but it’s what passes as understanding that seems to come too easily to our kind.

so that the more clear and transparent things became, the more my refusal showed through. I didn’t want to see things as they were. I had grown tired of that.

until bit by bit she had calmed down and loosened her grip on Epstein—loosened it out of trust, so that on another level her hold became tighter. Later, she didn’t push her father away as her brother and sister had.

One is always in the hold of the world, but one doesn’t physically feel its hold, doesn’t account for its effect. Cannot draw comfort from the hold of the world, which registers only as a neutral emptiness. But the sea one feels. And so surrounded, so steadily held, so gently rocked—so differently organized—one’s thoughts come in another form.

Tzimtzum, Klausner had repeated, and explained the term that was central in Kabbalah. How does the infinite—the Ein Sof, the being without end, as God is called—create something finite within what is already infinite? And furthermore, how can we explain the paradox of God’s simultaneous presence and absence in the world?

“Not a descendant,” Klausner said, but with a gleam in his eye, as if he were all too aware of the image he was playing to—the Jew who aspires to cliché, who, in his pious fight against extinction is willing to become a copy of a copy of a copy.

A health, I might have added, that I’d begun to suspect I might also possess, insofar as health is that part of one that recognizes what is making one unwell.

“Prepared for unhappiness. For happiness one doesn’t need to prepare.”

But nothing was found or discovered, and either he forgot what he was looking for or lost interest. Jewish literature would have to wait, as all Jewish things wait for a perfection that in our hearts we don’t really want to come.

love to dance, but by the time I came to understand that I ought to have tried to become a dancer instead of a writer, it was too late. More and more it seems to me that dancing is where my true happiness lies, and that when I write, what I am really trying to do is dance, and because it is impossible, because dancing is free of language, I am never satisfied with writing.

Narrative may be unable to sustain formlessness, but life also has little chance—is that what I wrote? What I should have written is “human life.” Because nature creates form but it also destroys it, and it’s the balance between the two that suffuses nature with such peace. But if the strength of the human mind is its ability to create form out of the formless, and map meaning onto the world through the structures of language, its weakness lies in its reluctance or refusal to demolish it.

And from the end of time, he leaped to time’s beginning, to the withdrawal of God to make space for the finite world, for time can only exist in the absence of the eternal.

and a small wardrobe, empty but for the smell of other centuries.

To be trapped and confined in a bewildering environment hostile to one’s inner conditions, in which one is fated to be obtusely misunderstood and mistreated because one can’t see the way out—from this, I don’t need to remind you, Friedman reminded me, Kafka made the greatest literature.

he himself rejoiced in the idea of dying. Not because he wanted to end his life, Friedman said, dropping his voice as he leaned toward me across the table, but because he felt he had never really lived.

And yet, Friedman said, holding up a thick finger—to truly understand why Kafka had to die in order to come here, why he was willing to sacrifice everything to do so, you have to understand a critical point. And it is this: it was never the potential reality of Israel that inspired his fantasies. It was its unreality.

Which is to say, Friedman said, that for the Jews, The Metamorphosis has always been a story not about the change from one form to another, but about the continuity of the soul through different material realities.

A sense of what Friedman might be asking of me began slowly to sink in: not to write the end of a real play by Kafka, but to write the real end of his life.

The sensation of seeing something long forgotten but intensely familiar washed over him, and in that instant it dawned on him that he hadn’t grown up after all.

Epstein could not help but feel that her attachment to them had something to do with the irritant at their core that had gone and produced such luster. She had brought him to a state of vibrancy by means of provocation.

he might have said something about the way, out of chaos, a few singular images are sometimes thrown up that come to seem, in their unfading vividness, the summation of one’s life, and all that one will take from it when one goes.

And then, to let him rest from what he had been, the authors of David ascribed to him the most plaintive poetry ever written. Had him, at the end of his days, stumble into the discovery of what was most radical in himself. Into grace.

When he looked down, he saw with wonder how the light falling from the streetlamp through the clear wrapping still glinted on the Virgin’s halo.

That he, a man born in Punjab Province to a farmer, should be sitting in New York City holding a masterpiece painted in fifteenth-century Italy—he felt a sudden urge to break the little painting in two and shivered.

To his brothers, such a thing would hold no value at all, and he felt a wave of sadness at a dista...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

As for my husband, I really had no idea how he would have responded to the news that I’d disappeared: it was very possible that he might have felt ambivalent, and perhaps even relieved at the prospect of being able to go through the rest of his life without me looking skeptically over at him.

But there had been so much restraint and silence between my husband and me that when we parted and broke into our separate light and volume at last, the person that came into view was impossible to hold close. Perhaps he didn’t wish to be held close, or couldn’t, for which I don’t blame him. And now, far enough on the other side of grief, I find I feel only surprise when I think of him. Surprise that for a time we ever believed we were walking in the same direction at all.

The book was filled with many fascinating things, and I remember that it went quite deeply into the ancient Greek words for time, for which there were two: chronos, which referred to chronological time, and kairos, used to signify an indeterminate period in which something of great significance happens, a time that is not quantitative but rather has a permanent nature, and contains what might be called “the supreme moment.”

Either as a result of this, or of the patience that naturally develops from being alone and confined to bed, I slowly became aware of a sharpening of my vision, and after experimenting with this clarity, studying the fibers on the blanket that stood up like the hairs on an insect’s leg, I discovered that I could also apply it when looking inward.

that for most of my life I had been emulating the thoughts and actions of other people. That so much that I had done or said had been a mirror of what was done and said around me. And that if I continued in this manner, whatever glimmers of brilliant life still burned in me would soon go out. When I was very young it had been otherwise, but I could hardly recall that time, it was buried so far below. I was only certain that a period had existed in which I looked at the things of the world without needing to make them subordinate to order. I simply saw, with whatever originality I was born

...more

His sense came from the belief that most people misunderstood the expulsion from the Garden of Eden to be punishment for eating from the Tree of Knowledge. But as Kafka saw it, exile from Paradise came as a result of not eating from the Tree of Life. Had we eaten from that other tree that also stood in the center of the garden, we would have woken to the presence of the eternal within us, to what Kafka called “the indestructible.”

But because we lack the capacity to act in accordance with our moral knowledge, all our efforts come to ruin, and in the end we can only destroy ourselves trying.

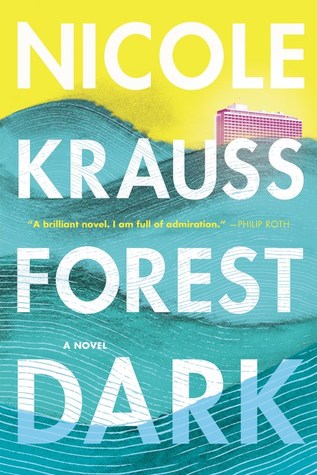

Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark, For the straightforward pathway had been lost.