More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He would just be telling people about his hard day’s work, but they would listen as though it were the best fable Hadi the liar had ever told.

He immersed himself in the story and went with the flow, maybe in order to give pleasure to others or maybe to convince himself that it was just a story from his fertile imagination and that it had never really happened.

Elishva opened up to Daniel about her conflict with her husband, Tadros, who buried an empty coffin for Danny against her wishes.

Elishva hadn’t agreed to go with them because her heart told her that her son was not dead. She didn’t look at the grave until Tadros himself died and was buried next to the grave of his son. It broke her heart to read the name of her son on the limestone marker, and even then she wouldn’t acknowledge that he was dead, despite the passing of the years.

Abu Zaidoun took Danny away by the collar. From the training camp, Daniel went straight to the front and never came back. From then on, Abu Zaidoun was Elishva’s sworn enemy.

Pronouncing the words with difficulty, he told her that he had to go out. She wanted to say, “Why are you going? You’ve just come back. Why would you leave me? Whenever anyone goes out that door, they never come back. It’s like a door that opens into a hole.”

Although he had clout in the neighborhood, he was still frightened by the Americans. He knew they operated with considerable independence and no one could hold them to account for what they did. As suddenly as the wind could shift, they could throw you down a dark hole.

“There are reports about criminals who don’t die when they’re shot,” he said. “Several reports from various parts of Baghdad. The bullet goes into the criminal’s head or body, but he just keeps walking and doesn’t bleed.

But there were two fronts now, Mahmoud said to himself—the Americans and the government on one side, the terrorists and the various antigovernment militias on the other. In fact “terrorist” was the term used for everyone who was against the government and the Americans.

“Mr. Sawadi,” he said, “I’d be careful going out—the police are all over the place. A man was killed this morning.”

The man was none other than Abu Zaidoun, the old barber, who was all skin and bones.

The medical report said he had died of a heart attack. Maybe the criminal had killed a man who was already dead. The old man’s sons were satisfied with this explanation, not having the energy to pursue a vendetta.

Others recalled the man’s long career and how he had been responsible for sending so many young men off to war.

He may have taken part in raids on some houses, and he wasn’t short of enemies, but no one knew who had killed him. It clearly wasn’t random.

That’s how everyone wanted to remember him; death gives the dead an aura of dignity, so they say, and makes the living feel guilty in a way that compels them to forgive those who are gone.

Umm Salim herself had once vowed to slaughter a sheep at her front door if God took revenge on Abu Zaidoun, but now she had forgotten all that.

If she asked God or Saint George the Martyr or the ghost of her son, they would tell her she didn’t need to ask forgiveness for Abu Zaidoun. She was fully entitled to seek revenge because it would strengthen her faith and give her ailing spirit the energy it needed to keep on living.

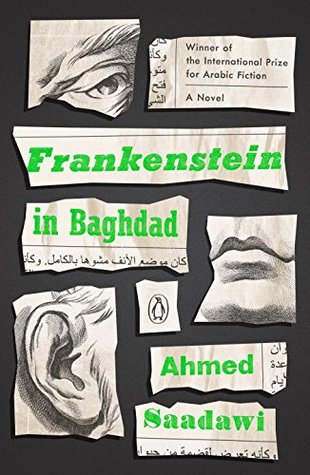

“Tell us the story of the corpse,” they said in unison. “The story of the Whatsitsname, you mean.” Hadi insisted on correcting them, using the name he had given his creation.

“You should forget that bullshit story of yours.” “Why? What’s happened?” “What’s happened! They’re looking for the guy who killed the four beggars and Abu Zaidoun and the officer they found strangled in the whores’ room in Umm Raghad’s house.”

“Those stories of yours are going to get you into trouble. When the Americans grab you, you’ve no idea where they’ll take you. God alone knows what charge they’ll pin on you.”

Without informing Aziz, he made a private decision not to mention the story of the corpse ever again.

Its body was sticky, as if it was smeared with blood or tomato juice.

He walked past her, and she glimpsed part of his face—it was the most horrible thing she had ever seen. It’s hard to believe God would create such a face; just looking at it was enough to make your hair stand on end.

Except for what was said about the blood or tomato juice, the other details were familiar: the big mouth like a gash right across the jaw, the horrible face, the stitches across the forehead and down the cheeks, the big nose.

The door swung wide open and beyond the doorway loomed the dark figure of a tall man. His blood froze in his veins as he saw the figure approach.

The yellow light of the lantern struck the strange man’s face—a face with lines of stitches, a large nose, and a mouth like a gaping wound.

Unlike the people from the charity, Faraj understood what Elishva meant when she talked about her son, but he hadn’t yet seen him for himself.

The old women were sad at first, because poor, crazy Elishva with that strange red scarf on her head had finally lost her mind. But late at night some people did see a young man coming out through her front door, wrapped in the darkness.

the young man had climbed the low wall of Hadi’s house and jumped up to the open area where the two rooms had collapsed on the upper floor of Elishva’s house. He had intended to go downstairs and strangle her in her bed. No one would bother to ask why such an old woman had died. They would say that God had snatched her soul as she slept, and then forget all about it.

The young criminal came down the stairs and saw her sitting with her oil lamp in the big room next to the street, praying and talking to Saint George. What she said struck a chord in his heart, even though he didn’t understand the language.

That spiteful woman had won people over with her story. It didn’t matter that it was made up; it was moving,

“Hilda’s upset, to tell the truth. She says she’ll never speak to you again. She’s not here with me now. She’s not listening to what I’m telling you, and she’d be upset if she found out I’d spoken to you.”

“He’s with me now,” Elishva continued. “He refuses to go out when people can see him. He goes out at night. From the roof. He disappears for days, but then he comes back.”

She wouldn’t answer calls from her daughters, and she wouldn’t ask to call them. Father Josiah laughed and tried to pat her on her skinny shoulder, but she replied that if he didn’t comply with her request, then next week she would go to the Saint Qardagh Church and would never go back to his.

He had spent the last few days in a state of permanent drunkenness, ever since that dark night when the frightening guest had visited him and he had tricked himself for a moment into believing it was a figment of his imagination and not his own creation.

He recalled the night when he was thrown through the air by the force of the explosion. He wished he had died right then.

No day passed without at least one car bomb. Why did he see other people dying on the news and yet he was still alive? He had to get on the news one day, he said to himself. He was well aware that this was his destiny.

Until that night Hadi had kept the promise he had made to himself during his conversation with Aziz in the coffee shop—he would forget about his story and never mention it to anyone again. But then he’d discovered the story was true, and he no longer found it amusing to tell in front of other people.

No one knew, not even Aziz, that the Whatsitsname, as Hadi called it, had come back to Hadi alive and standing on its own two feet.

There were serious things happening, and Hadi was merely a conduit, like a simple father or mother who produces a son who is a prophet, a savior, or an evil leader. They didn’t exactly create the storm that followed. They were just the channel for...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The team of astrologers and analysts that he headed had managed to collate all the information available about strange murders in Baghdad, and all signs pointed to one perpetrator. In every crime there was one victim, and the victim had usually been strangled. Accounts by witnesses were

“What does that mean, the One Who Has No Name? So, what’s his name?” “The One Who Has No Name,”

I don’t know whether that was just a lie.” “And the story you told me just now, isn’t that a lie too?” “No. I’d be upset if you thought that.”

What would happen if Mahmoud called that number now? He could tell her that he had taken her previous call and found out what kind of relationship she and Saidi had, and that he was now offering her some advice: “Forget Saidi, because he has no memory. He’s just a man of pleasure. You can try your luck with other men if you like. Try your luck with me, you devil woman.”

Mahmoud ordered a tea and, out of a desire to forget everything, surrendered himself to Hadi’s crazy story.

He believed that emotions changed memories, that when you lost the emotion associated with a particular event, you lost an important part of the event.

What if Hadi produces real evidence that a mythical creature of this kind existed? Would he really believe it?

“Honestly, I think everyone was responsible in one way or another. I’d go further and say that all the security incidents and the tragedies we’re seeing stem from one thing—fear.

The people on the bridge died because they were frightened of dying. Every day we’re dying from the same fear of dying.