More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 23, 2017 - April 3, 2018

He smelled like cigarettes. He built me bookshelves. He’d make both fists into devil horns, yell “metal!” and stick his tongue down past his chin. He pointed at me with a paintbrush: “Poor baby. You just want to feel all right.”

What if we did get together and I hurt him? I didn’t want to hurt him. I loved him. So much so that I’d bug him about the cigarettes and he’d tell me to back off and I’d quote statistics about lung-related death and he’d say we could all go at any time, wiped out by a bus, a train, an explosion like lightning, a heart attack on a mountain, a tumor in the brain, the skin, the breast, by your own hand when it’s all too much, or an AR-15 in a school or park or street so who gives a shit about a cigarette, what’s healthy or right or fair? There are so many reasons not to try. They all start with

...more

You could hear the music through my windows, a weird sort of soundtrack to the most scared I’ve ever been.

I’m trying to see her: reaching down the line of my life. She smelled like honey. She loaned me dresses.

tried to move like she moved—hands go here, feet here, ass like this—the same way I learned dialogue from Hurston, pacing from Selby, sentences from Woolf.

I want to say weeks, but I’m known to exaggerate, to add the extra ten feet the hero has to jump.

So loud a silence. I heard that book in my own apartment. My life collided with its pages.

“I wanted to get it out of me,” he said, and even though it would be years before I understood what he meant, before I put my own heart in the open and looked, really looked, I still nodded like I understood. “You can’t fix it if you can’t see it.”

On MSNBC, Cokie Roberts takes the question to Trump himself, bringing up incidents of white children telling their darker-skinned classmates they’ll be deported if he wins. “Are you proud?” she asks. “Is that something you’ve done in American political and social discourse that you’re proud of?” He tells her it’s a nasty question.

When I tell that story, people laugh. Probably because of how I tell it—humor as weapon, humor as shield.

Every woman should have such an advocate and the fact that our patient/doctor relationship is a privilege as opposed to a right makes me want to set the walls on fire. Look up—see the wall in front of you? Imagine it in flames.

“Oh, kid,” he said. “Write whatever you want.” A tidal wave of gratitude. “So long as it’s the truth.”

Louise Erdrich: “How come we’ve got these bodies? They are frail supports for what we feel”;

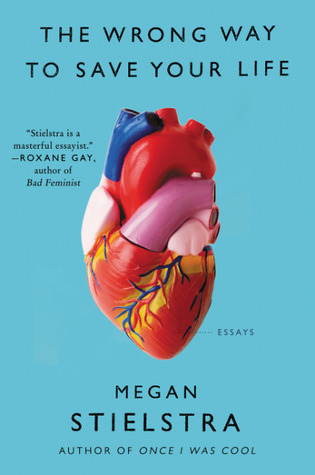

I’ve always engaged with the heart as a metaphor: a desire, a thing to survive, to heal from or shoot for. Now I know there’s nothing more real. We walk through the world at its leisure. We’re here at its mercy and with its blessing. At some point, we have to ask ourselves how we want to live.

Three months is not a long time, but that summer—a fucking glacier, a watched fucking pot.

to be an active participant in my life instead of responding to what was happening to me, to do something, to do something.

I’d been careless, I told them, even though hurting myself had taken all the care in the world.

He said, “You are the ones who can change it.” He said, “Where do you want to be standing?” I walked across the room to the opposite wall.

We should all be in awe of teenagers, of youth, youth artists in particular. Holy hell, the emotion! The love and the anger and the energy, all so huge, enough force to power a city. I think back to myself then, and I look at the young writers I work with now, and am blown away by their courage. It scares people, I think. We try to contain it. We teach them to hold back. To be “appropriate.” To be “respectable.” I wonder: What might happen if we got out of their way? What might happen if we actually listened?

A personal essayist spends a fair amount of time with this question, much of it in our own heads: What really happened? Why can’t I remember that part? Who was the guy in the blue shirt? That was a great shirt. I bet I could find that shirt online. And so on, ad nauseam.

Sometimes, I talk about emotional truth, how Gregor Samsa didn’t want to go to work so he turned himself into a bug.

There I met two French boys, a cute one who spoke a little English and a really cute one who spoke none at all. “He buy beer!” said the cute one, pointing at the really cute one, and the really cute one pointed at me and said, “Run, Forrest!”

No way would I tolerate other women being treated like this. Why do I allow it in my own goddamn head?

Think of how much time you spend trying to find your next love. Think of how much time you spend trying to find your next lay. What could you do with that time? What could you make?

No room for bullshit if you’re already full.

It was obvious and horrible and, in retrospect, one of the greatest things I’ve ever done. Where would any of us be if we hadn’t started somewhere?

“I don’t think I can,” I said. And I will never forget this. He said, “Megan. This is the fun part.”

“You had to win,” he tells me. “You can’t lose a fight about your own happiness. You can’t lose a fight about your own life.”

What gets covered depends on where you are, and who’s writing. And who’s editing.

My mic was my fist.

sans. I wanted to climb out of my skin. Instead, I got online and asked Twitter if I could start a dance party.

Eventually, Microsoft tweeted back at me. There were lots of exciting ways to use PowerPoint! They were here to help! Would I like suggestions?

There is a difference between common practices and best practices.

“Put on your what the fucking fuck hat,” he said, slamming around his office.

So much of who we are is tangled in place; a country, a city, a corner.

I didn’t want to be there anymore. That doesn’t mean it was easy to leave.

You see that, right? When you look down the course of your life? What you’ve made, how you’ve helped, how you’ve loved?

She reads aloud from “The End of Empathy” by Stephanie Wittels Wachs: “We’re never going to get anywhere if we continue to treat each other like garbage.” She reads poetry, like this from Mary Jo Bang: “We pretend we forgot that we said we’d be kind.” Whatever she does, for sure it won’t be a gun. Enough with the guns.

Some people will come after us no matter what we say. We might as well say things that matter.

In 2015, the music critic Jessica Hopper asked women and people from other marginalized communities to share their “first brush with the idea that they didn’t count.” There were thousands of replies, throwing a bright light on sexism in music including people who’d left the industry altogether for their own physical or emotional safety. “What songs or albums could we hear if people weren’t being told they aren’t supposed to be here?” Hopper told the Guardian.

It’s easy to see the truth when we do the work of looking.

Privilege isn’t blame or shame or fear. It’s responsibility.

You don’t have to maintain an impeccable credit score. Anyone who expects you to do [that] has no sense of history or economics or science or the arts. You have to pay your own electric bill. You have to be kind. You have to give it all you got. You have to find people who love you truly and love them back with the same truth. But that’s all.

It’s made me look very closely at how we use our platforms, whatever the size. The seemingly smallest gestures can mean the world to someone else.

That’s when we can ask hard questions, face difficult truths, make discoveries and go deeper and push and fight and learn through the work, and I think part of that includes a differentiation between the act of writing and the choice of when and if and how to share that writing. Maybe, for now, you’re just writing for yourself.

Maybe you’re writing for a teacher. Maybe, if your teachers do their jobs right and build spaces where art and ideas and individuals are all equally respected, you’ll choose to share it with the class. Maybe you’ll choose to perform it. To submit it. To hand it to ___________ and start a dialogue, or fuck _______________ and give it to the world.

Daddy’s voice is serious. Daddy uses this voice to talk about bullying and typography, say please and thank you, and don’t kick the dog. “We need to talk about the psychological impacts of deceptive marketing.”

Do you want to play, too? You can do this on your own: grab a sheet of paper and draw a horizontal line between two X’s. Do it. I’ll wait. The X on the left? That’s when you were born. The one on the right? That’s however old you are right now. Take thirty seconds and mark some X’s on that line for the moments that scare you; the big and the small, the wonderful and the awful, when you were six and twelve and twenty and forty. Don’t think too hard about it; just get it out of you.

See what you have to say. I wager you’ll find some beginnings there, some meat and emotion and story. Write them. Paint them, dance them, scream—make something.

“It’s okay if a story makes you sad,” I told him. “It’s okay if it makes you angry or afraid. These feelings are real. Let’s live them.”