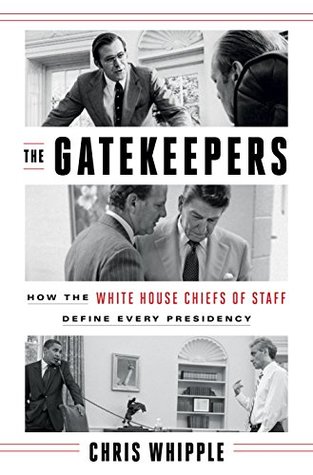

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 28 - May 12, 2019

“Every president reveals himself,” says historian Richard Norton Smith, “by the presidential portraits he hangs in the Roosevelt Room, and by the person he picks as his chief of staff.”

“The executive branch of the United States is the largest corporation in the world,” the adviser, H. R. Haldeman, would reflect years later. “It has the most awesome responsibilities of any corporation in the world, the largest budget of any corporation in the world, and the largest number of employees. Yet the entire senior management structure and team have to be formed in a period of seventy-five days.”

Because presidents have too many things to do. They need someone to organize issues for them, to organize decisions, to bring the politics and the policy together, to have outreach to interest groups, to make sure that relations with Congress are going as smoothly as possible, to make sure the scheduling is done in the most logical way, to set priorities. That can’t be done by the president himself—however smart or wise he is.”

Every president is destined to fail in some way, because the job involves a wider range of talents than any person has. And so, yes, every president should have a chief of staff who makes a complete whole. And few of them do.”

“The people who don’t succeed as White House chief of staff are people who like the chief part of the job and not the staff part of the job,” says Baker. “You’ve got to remember that you’re staff even though you’re powerful.”