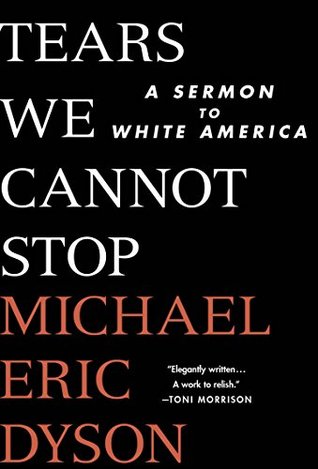

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 7 - February 19, 2018

What it comes to is that if we, who can scarcely be considered a white nation, persist in thinking of ourselves as one, we condemn ourselves, with the truly white nations, to sterility and decay, whereas if we could accept ourselves as we are, we might bring new life to the Western achievements, and transform them . . . The price of this transformation is the unconditional freedom of the Negro . . . He is the key figure in his country, and the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his.

The spoils we reaped from forcing people to work without wages and treating them with grievous inhumanity continue to haunt us in a racial gulf that seems impossible to overcome.

We have, in the span of a few years, elected the nation’s first black president and placed in the Oval Office the scariest racial demagogue in a generation. The two may not be unrelated. The remarkable progress we seemed to make with the former has brought out the peril of the latter.

What, then, can we do? We must return to the moral and spiritual foundations of our country and grapple with the consequences of our original sin. To do that we need not share the same religion, worship the same God, or, truly, even be believers at all. For better and worse, our national moral landscape has been shaped by the dynamics of a Christianity that has from the start been deeply intertwined with religious mythology and cultural symbolism.

But all of us, from agreeable agnostics to fire-and-brimstone Protestants, from devout Catholics to observant Jews, from devoted Muslims to those who claim no god at all, share a language of moral repair. That language is our common meeting ground, our tool of analysis, and yes, our inspiration for repentance, our hope for redemption.

But so much of what ails us—black people, that is—is tied up with what ails you—white folk, that is. We are tied together in what Martin Luther King, Jr., called a single garment of destiny. Yet sewed into that garment are pockets of misery and suffering that seem to be filled with a disproportionate number of black people. (Of course, America is far from simply black and white by whatever definition you use, but the black-white divide has been the major artery through which the meaning of race has flowed throughout the body politic.)

What I need to say can only be said as a sermon. I have no shame in that confession, because confession, and repentance, and redemption play a huge role in how we can make it through the long night of despair to the bright day of hope. Sermons are tough, not only to deliver, but, just as often, to hear. Yet, in my experience, if we stick with the sermon—through its pitiless recall of our sin, its relentless indictment of our flaws—we can make it to the uplifting expressions and redeeming practices that make our faith flow from the pulpit to the public, from darkness to light.

To repair the breach by announcing it first, and then saying what must be done to move forward.

It will make you squirm in your seat with discomfort before, hopefully, pointing a way to relief.

To paraphrase the Bible, to whom much is given, much is required. And you, my friends, have been given so much. And the Lord knows, what wasn’t given, you simply took, and took, and took.