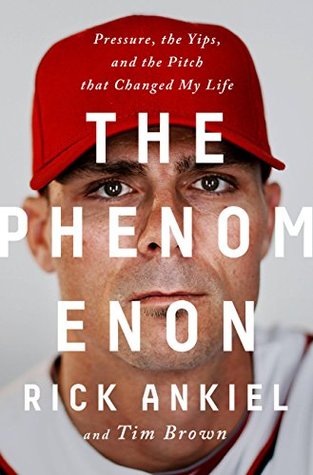

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Rick Ankiel

Read between

August 27 - September 11, 2022

The tally for the third inning: thirty-five pitches, two hits, two runs, four walks, five wild pitches, and, it turned out, one psyche forever hobbled.

There’s a blind spot. There’s something in there, deep in there, that’s not right. And he’s going to have to live with this for a while. Those boxers who get knocked out for the first time, they all bear the emptiness in their eyes. Presumably, 90 percent of it is from getting hit in the face so hard. But that other 10 percent? That’s their invincibility leaking out.

I was too small, and then I was too afraid, and even when I grew up there remained the notion that to challenge one’s father was to call out the whole universe into the middle of the street to decide who was the better man. And how long would that have lasted? A punch or two? And what would that have cost my mother in bruises?

On the ride home, Walt asked me if I thought I was ready for pro ball. I smiled. Scott had told me he’d ask me that. The question was meant as a challenge, like I could step up and play with the big boys or go hide in college with the other seventeen-year-olds.

Sports drew me out of my own head, from my insecurities and fears, my suspicion that I was the person my dad must think I was, because otherwise why would he say that stuff to me? Why would he be so angry?

Why the yips? Why some people and not others? Why the easy stuff? The routine throws? Why, if it can be contracted so easily, can it not be cured as easily? Why, if it can be summoned in a single pitch, can it not be buried in two or three or a thousand?

“The yips,” he said, “can be explained in both psychological and neuromuscular terms, and it’s extremely complicated. It’s very difficult to treat and very difficult to understand.… What it boils down to, a mistake is made, ultimate trust is eroded, pressure interferes with the lack of trust, and that compounds the problem. Now there’s anxiety, and a vicious cycle ensues.” Along come the obsessive thoughts, Dr. Oakley said, the failure, the pursuit of perfection now fouled by anxiety and more failure and more anxiety.

So which comes first, the mistake or the anxiety? Which causes the other?

I built walls against the approaching forces that surely would wreck the fastball I’d have to throw in eight hours. Those were the breathing exercises, the attempts to distract myself and drive whatever was surfacing back inside. Nearly every time, those walls would fall at the first sign of peril. What I’d think later was Bigger walls. I need bigger walls. And a moat.

So, for example, if a pitcher began throwing baseballs to the backstop and suffered, as a result, a panic attack right there on the mound, that pitcher’s psyche would be brought back to that moment—the sights, the sounds, the feel of the ball off his fingertips, and then the physical and emotional reactions to that pitch. That is, Dr. Oakley reconstructs the inaugural exposure to the yips so that the response is similar.

By turning my attention away from the hitter, away from the strike zone, away from the game, and to myself, my own problems, I’d acknowledged there was an issue. And the issue was me.

“Why is it that you can’t get the ball over the plate? It seems so simple.” So simple. That noise you just heard was what’s left of my hollow laugh.

I threw the pitch, which lowered the lever, which released the anxiety, like a cement mixer had emptied itself into my head.

My whole life I’d carried a shield, forged from the belief of who I thought I should be. What a man should be. That is, impenetrable. It’s what I became as a ballplayer too. I followed the best arm plenty of people had ever seen, and if it wasn’t the best, it was close enough, and that made me invincible. What was I without it? The only place that would have me unconditionally—a ballpark—looked me over and said, “Prove it. Try harder. Want it more. Suffer.” Thunk.

Rookie ball, man. In Tennessee. There were eighteen-year-olds on that team. One of them was named Yadier Molina. The future big leaguers were him and maybe one or two other guys. The former big leaguers? Just one that I counted.

My career, if there were to be one, would have to be about control. I’d control my mind, which would settle my heart, and control my effort, which would guide my fastball.

Mostly, I’d missed competing against the other guy rather than competing against myself, getting back to a game that would be settled by the width of the ball and the breadth of the man.

Almost seven years after it had happened the first time, I felt as though I’d left my body again. This time, however, there was no panic. My breaths were short. Not out of fear but in celebration. In joy. I could feel the game in my heart, in my soul. This time, I ran the bases on somebody else’s legs, watching from above. This time, I was cheering like the rest.

I’d been a Royal, a Brave, a National, an Astro, and a Met. I was a Cardinal in my soul, where it mattered. I still felt special in St. Louis and in that ballpark, because both had accepted me in sickness and in health, and those kinds of bonds stay bonds forever, especially in baseball-mad St. Louis.