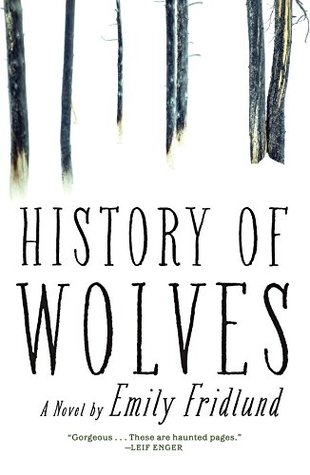

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It’s marvelous, and sad too, how good it can feel to have your body taken for granted.

I could do that. Give people what they wanted without them knowing it came from me. Without saying a word, Lily could make people feel encouraged, blessed. She had dimples on her cheeks, nipples that flashed like signs from God through her sweater. I was flat chested, plain as a banister. I made people feel judged. Winter collapsed on us that year. It knelt down, exhausted, and stayed.

My mother believed in God, but grudgingly, like a grounded daughter.

It seemed unfair to me that people couldn’t be something else just by working at it hard, by saying it over and over.

Later, I could get that drizzle feeling just about any time I saw a kid on a swing. The hopelessness of it—the forward excitement, the midflight return. The futile belief that the next time around, the next flight forward, you wouldn’t get dragged back again. You wouldn’t have to start over, and over.

By their nature, it came to me, children were freaks. They believed impossible things to suit themselves, thought their fantasies were the center of the world. They were the best kinds of quacks, if that’s what you wanted—pretenders who didn’t know they were pretending at all.

As if they weren’t interchangeable to me, like geese, like birds with their reliably duplicate markings. I marveled that I could seem so particular and durable to them. So distinct.

You know how summer goes. You yearn for it and yearn for it, but there’s always something wrong. Everywhere you look, there are insects thickening the air, and birds rifling trees, and enormous, heavy leaves dragging down branches. You want to trammel it, wreck it, smash things down. The afternoons are so fat and long. You want to see if anything you do matters.

Maybe if I’d been someone else I’d see it differently. But isn’t that the crux of the problem? Wouldn’t we all act differently if we were someone else?

So many people, even now, admire privation. They think it sharpens you, the way beauty does, into something that might hurt them. They calculate their own strengths against it, unconsciously, preparing to pity you or fight.

As Mary Baker Eddy says, “Become conscious for a single moment that Life and intelligence are purely spiritual,—neither in nor of matter,—and the body will then utter no complaints.”

I’ve found that some people who’ve done something bad will just go ahead and condemn everyone else around them to avoid feeling shitty themselves. As if that even works. Other types of people, and I’m not saying you’re this, necessarily, but I’m just putting it out there, will defend people like me on principle because when their turns come around, they want that so badly for themselves.

I saw then that I was just a part of the evil that took him, the one who arrived just in time for, and presided over, his disappearance. That’s all I was to her now.

The pickup was on loan from a church acquaintance of my mother’s, someone who’d heard about the trial and wanted to show the difference between true Christians and false ones.

What’s the difference between what you want to believe and what you do? That’s what I should have asked Patra, that’s the question I wanted answered,

And what’s the difference between what you think and what you end up doing? That’s what I should have asked Mr. Grierson in my letter—Mr.

It’s not what you do but what you think that matters. Mary Baker Eddy tells us heaven and hell are ways of thinking. We need to know the truth of that, pray to understand that death is just the false belief that anything could ever end. There’s no going anywhere for any of us, not in reality. There’s only changing how you see things.”