Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 5 - March 10, 2023

To cement the relationship, he arranged meetings with Milliken and himself at Richberg’s home, so the project’s principals could meet. This personal handling did the trick.

The problem, Regnery argued, was that the book market was not a free market. Rather, it had become a New York–centered, liberal-controlled industry in which books of a conservative bent could

make little headway no matter how promising their sales.

It was an insidious sort of bias, Regnery reasoned. Liberals could never be expected to publish or promote conservative books, so how could such books ever gain public notice?

The biggest threat for a new book was not bad reviews but no reviews at all, and most major papers overlooked Labor Union Monopoly. The

The New York Times, on the other hand, dismissed the book’s “hysteria”

calling the author and work “bitter,” “biased,” and “unfair.”

Regnery saw in these

results evidence of “a most effective form of censorship of ideas...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

His belief that the usual channels of promotion and sales were blocked for conservatives led Regnery to develop alternative networks for book distribution. He made efforts early on to build relationships with more amenabl...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

For Regnery, calling on Manion paid off: the radio host plumped the book during his broadcast “Dictatorship by Labor” and a few weeks later brought Richberg onto the show to discuss his work.

This was a fundamental theory of the conservative movement: that alternative outlets for disseminating their ideas were necessary because they wouldn’t receive fair hearing in the established media.

Were the barriers real?

prompting Time to declare Sheboygan “the most hate-ridden community in the U.S.”

beatings sent a few nonstrikers to the hospital for extended stays.

The Kohler factory was stocked with weapons in anticipati...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Even those not invested in these conspiratorial interpretations grew interested in the controversy.

journalistic lynching party.”

The circular excoriated Manion as “America’s closest thing to a fascist in the intellectual world; Kohler his counterpart in the industrial field.”

But independence had its benefits. Individual contracts greatly reduced the risk of another widespread blackout. If one station decided not to air a program, that decision would affect only one listening area. Further, station owners would only be concerned with the reactions of local listeners, rather than having to ascertain whether the broadcasts would be palatable on a national level.

at NBC or CBS, where it referred to a group of stations contracted with one company that would provide the bulk of its programming.

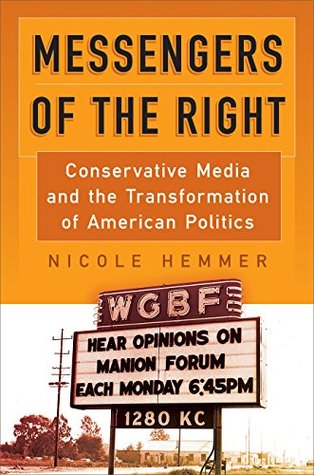

The Manion Forum provided only one program. But in the sense that he created a network of stations from coast to coast airing the Manion Forum on a weekly basis,

Even before the break with Mutual, Manion regularly referred to the “Manion Forum network,” an independent conservative ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The Manion Forum now had compelling evidence to back its charges of exclusion, which reinforced its populist message. See? it suggested. There really are powerful forces seeking to silence us.

now-familiar interpretation of the media landscape.

Conservatives stood outside the institutions of power, liberals inside. From this privileged position, liberals slanted news and opinion in their favor and silenced conservative critics whenever they could.

Facing these barriers to access and control, conservatives had to create new institutions, new conduits, new ne...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

but cajoled by their audiences and readers they began holding rallies and establishing organizations that channeled the passions they stirred into meaningful action.

Each “What You Can Do” segment focused on a different piece of legislation, detailing not only its substance and impact but the “arguments to use in writing your Congressman,” “WHEN to do your letter-writing,” and “whom to write to.”

Conservatives picked up on the example of the Scandinavians, who had faced their own Khrushchev visit in August. News of the visit roiled the press in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, generating plans of mass protests in Sweden.

The organization ran an open letter to Eisenhower in major American newspapers, outlining ten reasons not to exchange visits with Khrushchev and urging the president to rescind his invitation. Ads included a petition for readers to circulate among their neighbors and then send to the White House, a way of encouraging active engagement with the issue while also showing the breadth of popular support for CASE.6

It was a pivotal moment in the shift from conservative anti-interventionism to conservative hawkishness.

Postwar conservative organizing centered on young people, particularly those in colleges and universities.

(One measure: the three most popular speakers on college campuses in 1962, in order, were Barry Goldwater, Bill Buckley, and Martin Luther King Jr.)

The real threat, Kirk maintained, came from “dogmatic Rationalism,” which he argued sought to deny free will and spirituality.

How could students replicate his conversion experience without access to the tracts he relied on?

had been poring over back issues of American Opinion, the society’s magazine, and marveled how Welch had gotten it right, time and again. In fact,

“It’s amazing how it seems to work out as Bob

Easily lampooned as a loony secret society that saw communists lurking in every shadow,

Not until 1961 did journalists discover the “radical right” and “ultraconservatives.” Once they did, though, the right became a media obsession. Soon just about every major newspaper and magazine was devoting column space to the problem of the “radical right.”

There was something titillating about the idea of a secret society promoting accusations

of presidential conspiracy, and journalists pounced.

The authors, he pointed out, all admitted that dissatisfaction with liberal governance stirred conservative agitation. Where he believed they went wrong was in assuming such dissatisfaction was irrational.

Manion countered conservatism was instead “the logical reaction to the failure of liberal policies.

while others—National Review publisher William Rusher chief among them—preferred to keep a cautious distance and allow events to set the course. Still others, like Manion, argued conservatives should quietly develop alternatives to the society while publicly continuing their assault on established media for its efforts to discredit conservatism.11

The newsletters previewed upcoming guests,

but they also announced news and activities, promoted conservative books, kept readers informed of Manion’s in-person events, and carried reports of Conservative Club activism.

His experience in politics led Manion to believe smaller groups would have all the benefits of teamwork without the divisiveness larger groups tended to invite.

Through the newsletter, Manion directed these clubs toward study, discussion, and political action. Some of these activities focused on turning club members into “well versed spokesmen for conservatism,” conversant in both conservative philosophy and current events. Thus reading and discussion topped the priority list.