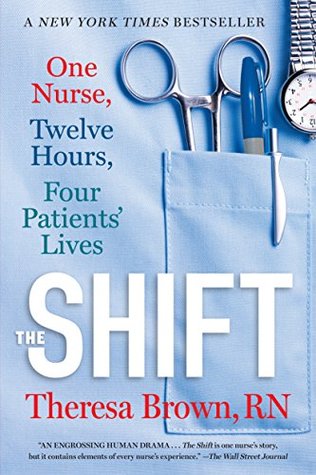

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 11 - January 26, 2019

You don’t always know because what goes on inside human bodies can be hidden and subtle. This job would be easier if there weren’t such a narrow divide between being the canary in the coal mine and Chicken Little.

Amid the many uncertainties of the shift there is one thing I know for sure. Am I ready and up to the job? Yes. Today, and every day, for the sake of my patients I have no other option; the answer has to be, and always is, Yes.

In my work with cancer patients I have found that the specter of death powerfully connects us to life.

Odysseus visited Hades seeking knowledge of the future from the prophet Tiresias. Ray came to us as a bearer of the rarest and most precious knowledge to be had on an oncology floor: that people make it. The miracle of oncology is that patients confront their own possible death, and move on.

This is nurses’ work and it’s a privilege to do it. It’s not every day you get to give someone her life back by hanging an IV,

do this all day long: run through a mental checklist that changes unpredictably. Of course I have things written down, but nurses spend the shift recalibrating the tasks we have and their urgency.

Ill health, and especially cancer, takes all comers.

John Keats, the nineteenth-century poet, recognized the challenges posed by lack of hard knowledge and the strength it takes to endure in such situations by coining the term “Negative Capability,” which he defined as: “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

When possible, touch in the hospital should come with a dose of kindness.

It feels good to think that the love of family or friends can bring on a turnaround that science can’t explain.

It’s very hard when patients see “their” doctor on rounds in the hallways and that MD fails to stop at their room or even say hello. I also don’t have what I consider a good enough explanation for why we do things this way. The system’s teaching efficiency doesn’t matter to the people who are sick; all they want is for the person they know and trust to be taking care of them.

“I was so worried about him, and he did great.” “Well,” he says, “If we could know the future our jobs would be a lot easier.” He briefly makes full eye contact and I see again what I first liked about him this morning: underneath the tiredness, the working so hard just to stay afloat, there’s a humaneness that impresses me.

To be in the eternal present of illness and unease, never knowing the future. It’s where my patients live so I, ever hopeful, live there with them.

The basics of life seem ordinary only if you’ve never faced losing them.

He doesn’t remember saying something that changed my life, but I do,