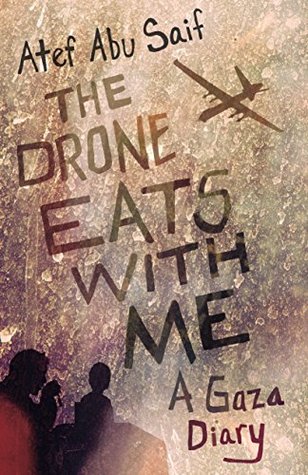

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

His guest for the discussion starts to discuss the despair that hangs over so many young people, especially with regard to their futures; how trapped they feel being unable to travel, study, or make a career outside of the Strip.

Jabalia is the largest refugee camp in all of Palestine, home to over one hundred thousand Gazans in only 1.4 square kilometers.

It is 3:30 a.m. Monday, 7 July 2014. A date to remember.

This was 27 December 2008 and that war lasted until 18 January 2009. The next war broke out on 14 November 2012, dubbed “Pillar of Defense” by the Israelis.

Every single human being in Gaza, whether walking on foot, riding a bicycle, steering a toktok, or driving a car, is a threat to Israel now. We’re all guilty until proven otherwise, and how are we ever going to do that, whether alive or not? Your innocence doesn’t matter—you have to abandon that. Survival is your only care.

The mobile network is down. This is often the case during drone attacks. It interferes with their communications, so the Israelis simply disable them.

They could hardly have been thinking about that gunship out there in the darkness, watching them, or the anger it stored, as they cheered and shouted at the match. They could hardly have imagined its maw, the gaping mouth of its gun turret, salivating with hunger for their souls.*

an explosion rocks the building from the east, the flash lighting up the room a split second before the sound. A moment later, a thick cloud of sand is gliding across the lounge from the window behind us. An orange orchard it seems, a hundred meters away, has been attacked.

Death is so close that it doesn’t see you anymore. It mistakes you for trees, and trees for you. You pray in thanks for this strange fog, this blindness.

One missile strikes Sheikh Radwan Cemetery. A reporter comments on the strange fate of the corpses interred there—many of whom were killed in previous bombings—finding themselves once more under attack.

Our fates are all in the hands of a drone operator in a military base somewhere just over the Israeli border. The operator looks at Gaza the way an unruly boy looks at the screen of a video game. He presses a button and might destroy an entire street. He might decide to terminate the life of someone walking along the pavement, or he might uproot a tree in an orchard that hasn’t yet borne fruit. The operator practices his aim at his own discretion, energized by the trust and power that has been put in his hands by his superiors.

We all sit around five dishes: white cheese, hummus, orange jam, yellow cheese, and olives. Darkness eats with us. Fear and anxiety eat with us. The unknown eats with us. The F16 eats with us. The drone, and its operator somewhere out in Israel, eats with us.

Death is the duck hunter lying in the reeds on the bank of the river. No one sees him; he wears perfect camouflage and picks off each innocent creature unseen.

Whenever you remember all these things, and also remember your desire not to remember any of them, you realize that memory is something forced upon you. People do not choose to remember; they are compelled to.

All those who have survived the onslaught on the beach have already fled inland and taken up residence in one of the UNRWA3 schools scattered along the center of the Strip. Within a few hours these schools have transformed from peaceful havens of learning to overcrowded shelters, packed with fear and noise and discomfort. It’s an all too instantaneous flashback to the painful scenes of two years ago—the 2012 war—and, before that, the 2008–2009 war.

Who knows what this tree has witnessed over the decades—its thick branches, its steadfast trunk. This majestic plant has stood here, resolute, from a time when a small forest stretched all the way from the tents of Jabalia Camp to the sea; a forest I played in as a kid. Now this tree is all that remains of that wood, in a jungle of concrete and overcrowding.

the real question is not “How do you relate to the world around you?” but “How does the world relate to you?” Because, at most, you’re only ever a tiny detail in this complicated universe. You are only one person, barely a cog in an infinitely complex machine.

At times of war, there is always a lot of honeyed rhetoric bandied about, concerning the word “heroism.” But it’s just rhetoric. The only real heroism is survival, to win the prize that is your own life.

The army used tear gas all the time when I was a kid. Our mother taught us to always keep an onion in our pockets during army maneuvers; whenever we smelt tear gas we would tear into the onions, rub the oil into our hands, then hold them over our noses.

In total, over 300 people have been killed in this war so far, and over 2,200 injured. More than 330 houses have been destroyed, and some 1,200 damaged.

Every day, new statistics flood in. New ways of adding up the war, turning it into math.

They all set off towards Jabalia Camp.1 It was the same scene in 1948, and again in 1967; men, women, and children walked along the same road, accompanied by the same Red Cross vehicles.

In Jabalia Camp alone there are an estimated forty thousand displaced persons.

Who will convince this generation of Israelis that what they’ve done this summer is a crime? Who will convince the pilot that this is not a mission for his people, but a mission against it? Who will teach him that life cannot be built on the ruins of other lives?

Who will convince the international community that it has a responsibility to be objective when things like this happen? No one, I suspect. Gaza has no one to help it. The people have only hope and their own resilience to fall back on. If that fails us, the sea may as well rise up and flood the land.

The number of people injured has reached over 3,300. Some 670 houses were destroyed and more than 2,000 were damaged.

nobody will ever ask to hear the stories behind these numbers either. Nobody will uncover the beauty of the lives they led—the beauty that vanishes with every attack, disappears behind this thick, ugly curtain of counting.

In time, you start to distinguish between the different types of attack. By far, the easiest distinction you learn to make is between an air attack, a tank attack, and an attack from the sea.

In the 2008–2009 war, a famous massacre was committed in Ezbet Abed Rabbo that has since been acknowledged in the UN’s Goldstone Report.1 Everything was destroyed. Not a single house survived the destruction. Corpses remained under the rubble for a week.

Four days into the war, when I first realized I was dateless, the only fact I could be certain of was how long the war had lasted for. Your life is bound by the terms of this war; everything is tied to its rhythm, its discourse, its sounds and silences. You know exactly which day of the war you’re on: today is Day 19.

Rubble is the only permanent image I have when I close my eyes.

Last night my friend Hisham, who works at Beit Hanoun Hospital, phoned to say that the Israelis had bombed the hospital there. Shells struck the X-ray room and the operating theater. Patients, nurses, and doctors—all were terrified. Hisham’s three-minute description of the chaos concluded with the insistence that some kind of intervention from the Red Cross or the UN must come.

People’s homes now merge and weave together all over Gaza, like threads in a woolen scarf, knitted together by an old woman. Different colors, different materials, different styles.

I SAW THEM WITH MY OWN EYES. Death’s footsteps. In the aftermath of feasting on a dozen other lives. His disgusting smell still fills the air. The echo of his roar still rings in my ears. The remnants of his supper still lie scattered around me.

Death still lingers in it, like a djinn hiding quietly somewhere in its heavy metal, like a sleeping volcano ready to erupt at any minute.

Everyone expects death every night. But he’s a visitor who observes no rules, respects no codes of behavior. Hence there’s no point in expecting him at any particular time; he’ll always be late or early. And the moment you stop thinking about him, he shakes the ground underneath you and destroys the sky above your head.

If death were a person you could talk to, I would beg him to be gentle and come as softly as he could.

It’s the same logic my friend Faraj is using when he distributes his family every night among different rooms of the house. This family of seven people sleeps in three different rooms. If a shell lands on one room, other members of the family will survive.

Death wouldn’t let them go, knew where to look for them, followed their every footstep.

Everything becomes normal. The barbarity of it, the terror, the danger. It all becomes positively ordinary.

I write my weekly article for tomorrow’s edition of Al-Ayyam. The article starts with the words “We are OK in Gaza.” But it’s a lie; we are never OK. Nonetheless, hope is what you have even at the worst of times. It is the only thing that can’t be stripped from you. The only part of you the drones or the F16s or the tanks or the warships can’t reach. So you hug it to yourself. You do not let it go. The moment you give it up you lose the most precious possession endowed by nature and humanity. Hope is your only weapon. It always works. It never betrays you. It never has before. And it will not

...more

The street was named “Jala’a” in the late ’50s after Israeli forces withdrew from Gaza City, having occupied it for a few months in ’56. It means “withdraw” or simply “leave,” but now stands as just another sign that they haven’t.

The occupation is now truly twenty-first century—the best drone technology in the world is being deployed up there, just to keep us occupied.

A month of non-stop, merciless bombardment has made them doubtful of the war ever ending. For them, war has become an everyday song, forever playing in the background. Drones, F16s, warships, tanks: these are the instruments of the orchestra, playing the new song of their lives.

A town that was flourishing a month ago has been reduced overnight to a camp, a city of tents. Palestinians have the same image of their entire country, as it happens, burned into their memory after the 1948 war: an image of an entire nation of civilized people reduced to a sea of refugee camps, stretching as far as the eye can see.