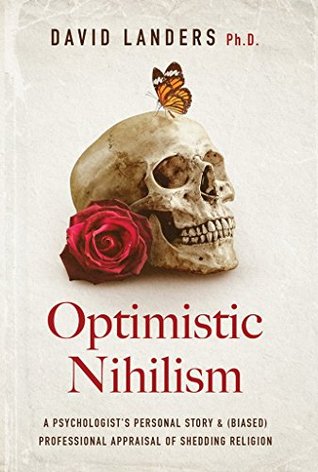

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 27 - May 1, 2020

If we modern atheists truly want our message to be heard, we need to rein in the vicious and degrading attacks. Hostility never convinced anyone of anything; it’s only engaging for the people who are already on your side.

In my gut, knowing the truth simply trumps peace of mind. I need to be in touch with reality as much as possible, regardless of how much it hurts.

Perhaps I lived through my execution twenty times; once I even thought it was for good: I must have slept a minute. They were dragging me to the wall and I was struggling; I was asking for mercy. I woke up with a start and looked at the Belgian: I was afraid I might have cried out in my sleep. But he was stroking his moustache, he hadn’t noticed anything. If I had wanted to, I think I could have slept a while; I had been awake for 48 hours. I was at the end of my rope. But I didn’t want to lose two hours of life: they would come and wake me up at dawn, I would follow them, stupefied with sleep

...more

Telling the truth seemed more important than averting suffering. Maybe suffering shouldn’t be avoided at all costs. Maybe if we would just face the horrors of our lives they wouldn’t be as horrible as we anticipate. And even if they are, maybe they should simply be respected and experienced as the horrors that they are.

There is no terror in a bang, only in anticipation of it.

We don’t want to consider that innocent people are victimized randomly, which makes us feel safe and in control. Furthermore, when we blame victims—whether of rape or poverty or whatever—it helps us minimize our obligation to help them.

I ain’t happy about it, but I’d rather feel like shit than be full of shit.

When we feel unable to tolerate the tension and confusion aroused by complexity, we “resolve” that complexity by splitting it into two simplified and opposing parts, usually aligning ourselves with one of them and rejecting the other. As a result, we may feel a sort of comfort in believing we know something with absolute certainty; at the same time, we’ve over-simplified a complex issue, robbing it of its richness and vitality . . . Feelings of anger and self-righteousness often accompany this process, bolstering our conviction that we are in the right and the other side in the wrong.

...more

we can become so obsessed with denying our fate that we often compromise the quality of the limited time we do have!

Quite clearly, the most enticing method to manage one’s terror is religion. In addition to providing a soothing culture in which to belong, religion makes everything we do much more meaningful than it seems. Our behavior is no longer human (that is, animal) activity but now spiritual, glorifying the Creator or otherwise becoming part of His Plan.

What are we to make of a creation in which the routine activity is for organisms to be tearing others apart with teeth of all types—biting, grinding flesh, plant stalks, bones between molars, pushing the pulp greedily down the gullet with delight, incorporating its essence into one’s own organization, and then excreting with foul stench and gasses the residue . . . Creation is a nightmare spectacular taking place on a planet that has been soaked for hundreds of millions of years in the blood of all its creatures.

The most recent data I’ve seen is that we are waiting longer and marrying older, and the divorce rate is declining!

What would we think of an earthly father who starved two of his children and fed only the third even though there was enough food to go around? And what would we think of the fed child expressing her deeply felt gratitude to her father for taking care of her needs, when two of her siblings were dying of malnutrition before her very eyes?

By thanking God for our comfortable American lives of air conditioning, grocery stores bursting at the seams with food, functioning automobiles all our own, magical cell phones, gigantic wedding rings, and yes, healthy children, we are—by default—validating God’s choice to neglect the majority of the world who are deprived of these luxuries.

The universe is not divine. God is not good. Nothing is tending to our prayers. Our beliefs in holiness and magic are merely coping strategies—defense mechanisms—whose obvious and only goals are to help the living feel better in the face of the brutality of reality.

“The fact that a believer is happier than a skeptic is no more to the point than the fact that a drunken man is happier than a sober one.”

True, man will then find himself in a difficult situation. He will have to confess his utter helplessness and his insignificant part in the working of the universe; he will have to confess that he is no longer the centre of creation, no longer the object of the tender care of a benevolent providence. He will be in the same position as the child who has left the home where he was so warm and comfortable. But, after all, is it not the destiny of childishness to be overcome? Man cannot remain a child for ever; he must venture at last into the hostile world.

And of course, we have to acknowledge that there will be no memories of any sort eventually: Even if the human race does not prematurely destroy itself through war, overpopulation, or other ecological catastrophe, the earth will eventually be devoured by the cosmos. It’s a matter of time before all evidence that humans ever existed is gone.

Since experiences are all we have, let us have as many as we can. Let us also live them heroically . . . without any hope or regret, without any illusions about their ultimate significance. Let us live them with the sense that we, and not any God, are the masters of our fate, and let us live them in revolt against false answers to the problem of life . . . That Sisyphus is an absurd hero to Camus is not surprising. What is surprising is this. Camus imagines Sisyphus happy as he walks down the mountain to begin pushing the rock back up. Why? Because he has made his own fate. And because he can

...more

Life is not about faith or obsessing about the future, whether with hope or anxiety. It’s about simply existing, with courage, honesty, and authenticity. These philosophers seem to believe that “What is the meaning of life?” is a silly question. There is no objective meaning to, no extrinsic purpose of, and no legitimate transcendence from the human condition. The most meaningful experience starts with facing this meaninglessness courageously!

In action, in desire, we must submit perpetually to the tyranny of outside forces; but in thought . . . we are free, free from our fellow men, free from the petty planet on which our bodies impotently crawl, free even, while we live, from the tyranny of death.

As long as I’m not dead, I’m alive. This is the mantra of the faithless: The miracle is happening right now, and you’re gonna miss it if you don’t slow down and stop fantasizing about the future.

We lose our attraction to materialism and rat-racing, because we can now perceive them for what they are, clingy acts of desperation to avoid these thoughts—these nihilistic thoughts that won’t kill us after all—and which may actually enrich us, to our amazement.

The purpose of life is, in this view, simply to live fully, to retain one’s sense of astonishment at the miracle of life, to plunge oneself into the natural rhythm of life, to search for pleasure in the deepest possible sense . . . On this one point most Western theological and atheistic existential systems agree: it is good and right to immerse oneself in the stream of life.

Although there is no objective meaning to life, its value is immeasurable.

Ernest Becker might have argued that we can be so emotional about sports because our team is a culture upon which we rely for a sense of belonging and esteem, and maybe even to help us feel bigger and better than we really are.

suspect that very, very few people throughout history on the verge of killing someone somehow changed their minds at the last minute because they were reminded of the sixth commandment.