More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The Epic of Gilgamesh is best known from a version called ‘He who saw the Deep’, which circulated in Babylonia and Assyria in the first millennium BC. The Babylonians believed this poem to have been the responsibility of a man called Sîn-leqi-unninni, a learned scholar of Uruk whom modern scholars consider to have lived some time about 1200–1000 BC. However, we now know that ‘He who saw the Deep’ is a revision of one or more earlier versions of the epic.

the work of an anonymous Babylonian poet who lived more than 3,700 years ago.

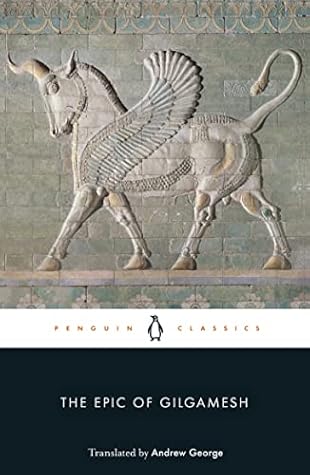

THE EPIC OF GILGAMESH ‘Humankind’s first literary achievement … Gilgamesh should compel us as the well-spring of which we are inheritors … Andrew George provides an excellent critical and historical introduction’ Paul Binding, Independent on Sunday

Preface to the Second Edition

A Note on the Translation

Poetry in Akkadian is distinguished by a rigorous formality. This translation, unlike some others (especially those of non-Assyriologists), seeks to give the reader a feel for the formal features of this poetry by translating line by line and replicating the structures that organize the poetry.

In older poetry a single verse may occupy two or even three lines on the tablet. In the first millennium one verse usually occupies one line, though sometimes two verses are doubled up on to a single line of tablet.

Some explanation is needed of the conventions that mark damaged text:

Note in addition the following convention:

A good anthology of Babylonian literature is Benjamin R. Foster, From Distant Days: Myths, Tales and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia (Bethesda, Md.: CDL Press, 1995).

Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History

Life in the Ancient Near East

Time Chart

Dramatis Personae

Introduction

Cuneiform writing was invented in the city-states of lower Mesopotamia in about 3000 BC, when the administration of the great urban institutions, the palace and the temple, became too complex for the human memory to cope with.

In the translations given in this book the texts are segregated according to time, place and language, allowing the reader to appreciate each body of material for itself.

The texts fall into four different chapters. To summarize,

Gilgamesh and ancient Mesopotamian literature

Literature was already being written down in Mesopotamia by 2600 BC, but because the script did not yet express language fully, these early tablets remain extremely difficult to read.

lower Mesopotamia was inhabited by people who spoke two very ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

One was Sumerian, a language without affinities with ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the medium of the earlies...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The other was A...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Mesopotamian culture was nothing if not conservative and since Sumerian had been the language of the first writing, more than a thousand years before, it remained the principal language of writing in the early second millennium.

Another masterpiece of Babylonian literature known from late in the Old Babylonian period is the great poem of Atramhasis, ‘When the gods were man’, which recounts the history of mankind from the Creation to the Flood.

Among the texts that were copied out by Ashurbanipal’s scribes was the Gilgamesh epic, of which the library may have possessed as many as four complete copies on clay tablets.

With its reflections on good and bad government the Gilgamesh epic certainly came into this category,

1 A damaged masterpiece: the front side of one of the better preserved tablets of the Gilgamesh epic

The setting of the epic

The central setting of the epic is the ancient city-state of Uruk in the land of Sumer. Uruk, the greatest city of its day, was ruled by the tyrannical Gilgamesh, semi-divine by virtue of his mother, the goddess Ninsun, but none the less mortal.

His reign, which the list of kings holds to have lasted a mythical 126 years, falls in the shadowy period at the edge of Mesopotamian history, when, as in the Homeric epics, the gods took a personal interest in the affairs of men and often communicated with them directly.

The epic in its context: myth, religion and wisdom

We know from many ancient Mesopotamian sources, in Sumerian and in Akkadian, that the Babylonians believed the purpose of the human race to be the service of the gods.

The divine element in mankind’s creation explains why, in obvious distinction from the animals, the human race has selfconsciousness and reason. It also explains why, in Babylonian belief, men live on after death as spirits or shades in the Netherworld – as reported in Enkidu’s dream of the Netherworld in Tablet VII and in the Sumerian poem of Gilgamesh and the Netherworld.

Foremost among these Sages was the fish-man Oannes-Adapa, who rose from the sea. Government, society and work were thus imposed on men.

1 The Standard Version of the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: ‘He who saw the Deep’ Tablet I. The Coming of Enkidu

2 The Sumerian Poems of Gilgamesh

The Death of Gilgamesh: ‘The great wild bull is lying down’

Fragments of Old Versions of the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic

After a break, Gilgamesh is explaining to Shiduri how his friend died and how thus he learnt the fear of death.

The text may be the outcome of a faulty memory.

The texts thus established are now ready for translation into English: