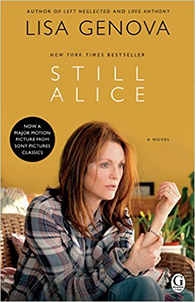

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

She thought about the books she’d always wanted to read, the ones adorning the top shelf in her bedroom, the ones she figured she’d have time for later. Moby-Dick. She had experiments to perform, papers to write, and lectures to give and attend. Everything she did and loved, everything she was, required language.

She wanted to read every book she could before she could no longer read.

She laughed a little, surprised at what she’d just revealed to herself. Nowhere in that list was there anything about linguistics, teaching, or Harvard. She ate her last bite of cone. She wanted more sunny, seventy-degree days and ice-cream cones.

She was in the best physical shape of her life. Good food plus daily exercise equaled the strength in her flexed triceps muscles, the flexibility in her hips, her strong calves, and easy breathing during a four-mile run. Then, of course, there was her mind. Unresponsive, disobedient, weakening.

She thought about the sabbaticals apart, the division of labor over the kids, the travel, their singular dedication to work. They’d been living next to each other for a long time.

Even biographies not saturated with disease were vulnerable to holes and distortions.

“I’m so afraid of looking at you and not knowing who you are.” “I think that even if you don’t know who I am someday, you’ll still know that I love you.”

“What if I see you, and I don’t know that you’re my daughter, and I don’t know that you love me?” “Then, I’ll tell you that I do, and you’ll believe me.”

The mother in her believed that the love she had for her daughter was safe from the mayhem in her mind, because it lived in her heart.

More and more, she was experiencing a growing distance from her self-awareness. Her sense of Alice—what she knew and understood, what she liked and disliked, how she felt and perceived—was also like a soap bubble, ever higher in the sky and more difficult to identify, with nothing but the thinnest lipid membrane protecting it from popping into thinner air.

“I’m losing my yesterdays. If you ask me what I did yesterday, what happened, what I saw and felt and heard, I’d be hard-pressed to give you details.

I have no control over which yesterdays I keep and which ones get deleted. This disease will not be bargained with. I can’t offer it the names of the United States presidents in exchange for the names of my children. I can’t give it the names of the state capitals and keep the memories of my husband.

My brain no longer works well, but I use my ears for unconditional listening, my shoulders for crying on, and my arms for hugging others with dementia.

“My yesterdays are disappearing, and my tomorrows are uncertain, so what do I live for? I live for each day. I live in the moment.

Her ability to use language, that thing that most separates humans from animals, was leaving her, and she was feeling less and less human as it departed. She’d said a tearful good-bye to okay some time ago.