More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Why is talking about Alzheimer’s important? Conversation fuels social change. Talking about Alzheimer’s is crucial for bringing your excluded, alienated neighbors with Alzheimer’s and their families back into community, for eradicating the stigma and shame people with Alzheimer’s have endured for too long, for creating the advocacy and urgency needed to fund the research that will lead to treatments and survivors.

Even then, more than a year earlier, there were neurons in her head, not far from her ears, that were being strangled to death, too quietly for her to hear them. Some would argue that things were going so insidiously wrong that the neurons themselves initiated events that would lead to their own destruction. Whether it was molecular murder or cellular suicide, they were unable to warn her of what was happening before they died.

The well-being of a neuron depends on its ability to communicate with other neurons. Studies have shown that electrical and chemical stimulation from both a neuron’s inputs and its targets support vital cellular processes. Neurons unable to connect effectively with other neurons atrophy. Useless, an abandoned neuron will die.

In all the expansive grandeur that was Harvard, there wasn’t room there for a cognitive psychology professor with a broken cognitive psyche.

“Would anyone like something to think?” asked Alice. They stared at her and at one another, disinclined to answer. Were they all too shy or polite to be the first to speak up? “Alice, did you mean ‘drink’?” asked Cathy. “Yes, what’d I say?” “You said ‘think.’ ” Alice’s face flushed. Word substitution wasn’t the first impression she’d wanted to make. “I’d actually like a cup of thinks. Mine’s been close to empty for days, I could use a refill,” said Dan. They laughed, and it connected them instantly. She brought in the coffee and tea as Mary was telling her story.

They shared stories of their earliest symptoms, their struggles to get a correct diagnosis, their strategies for coping and living with dementia. They nodded and laughed and cried over stories of lost keys, lost thoughts, and lost life dreams.

This thick book with the shiny blue cover represented so much of what she used to be. I used to know how the mind handled language, and I could communicate what I knew. I used to be someone who knew a lot. No one asks for my opinion or advice anymore. I miss that. I used to be curious and independent and confident. I miss being sure of things. There’s no peace in being unsure of everything all the time. I miss doing everything easily. I miss being a part of what’s happening. I miss feeling wanted. I miss my life and my family. I loved my life and family.

www.thewomensalzheimersmovement.org/prevention

There are currently about 5.7 million people in the US with Alzheimer’s, a staggering 50 million worldwide. At 65, 1 in 10 Americans have Alzheimer’s. At 85, it’s 1 in 3, fast approaching 1 in 2.

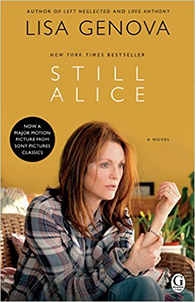

But I didn’t know how to feel with her. This is the distinction between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is feeling for someone and keeps us emotionally detached, our experiences separate. Empathy is feeling with someone and invites shared experience, intimacy, and connection. What does it feel like to have Alzheimer’s? The answer to this question would be the key to empathy versus sympathy. This was the seed for Still Alice.

Which writers inspire you? Oliver Sacks is my biggest inspiration. In fact, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat was really the spark that ignited my interest in neuroscience to begin with. There’s this quote from him: “In examining disease, we gain wisdom about anatomy and physiology and biology. In examining the person with disease, we gain wisdom about life.” That’s everything right there. That’s what I hope to do with my writing.