More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

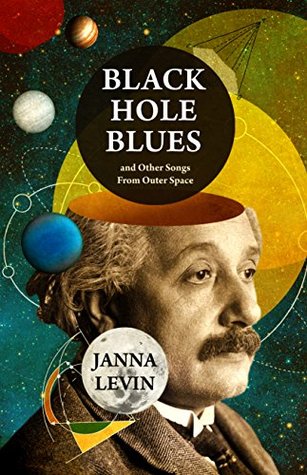

Based on complete access to LIGO and the scientists who created it, Black Hole Blues provides a firsthand account of this astonishing achievement: a compelling, intimate portrait of cutting-edge science at its most awe-inspiring and ambitious.

Somewhere in the universe two black holes collide—as heavy as stars, as small as cities, literally black (the complete absence of light) holes (empty hollows).

Tethered by gravity, in their final seconds together the black holes course through thousands of revolutions about their eventual point of contact, churning up space and time until they crash and merge into one bigger black hole, an event more powerful than any since the origin of the universe, outputting more than a trillion times the power of a billion Suns.

The black holes collide in complete darkness. None of the energy exploding from the collision comes out as light. No ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

That profusion of energy emanates from the coalescing holes in a purely gravitational form, as waves in the shape of ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

An astronaut floating nearby would see nothing. But the space she occupied would ring, deforming her, squeezing then stretching. If close enough, her auditory mechanism could vibrate in response. She would hear th...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Many scientists have invested their lives in the experimental goal to measure “a change in distance comparable to less than a human hair relative to 100 billion times the circumference of the world.”

As much as this book is a chronicle of gravitational waves—a sonic record of the history of the universe, a soundtrack to match the silent movie—it is a tribute to a quixotic, epic, harrowing experimental endeavor, a tribute to a fool’s ambition.

Rainer Weiss waves me in.

They’re constructing a recording device, not a telescope. The instrument—scientific and musical—will, if it succeeds, record Lilliputian modulations in the shape of space. Only the most aggressive motion of great astrophysical masses can ring spacetime enough to register at the detectors.

Colliding black holes slosh waves in spacetime, as can colliding neutron stars, pulsars, exploding stars, and as yet unimagined astrophysical spacetime cataracts.

LIGO headquarters is at Caltech, as is another prototype also humbled by the two full-scale instruments at remote sites.

Sixty years after Rai poked around the shoddy three stories to ask, “Hey, do you need a guy?” he is fundamentally unchanged—though not unevolved. Someone did need a guy, and Rai worked as a lab technician for two years before he made the transition back to student.

The idea came to him during a course he taught on the obscure subject of general relativity, Einstein’s theory of curved spacetime, as a junior professor. Rai says, “[MIT] figured that, hell, I had been to Princeton, so I must know something about relativity, right? . . . Well, what I knew about relativity you could stick in this finger. I mean general relativity. I’m not talking about special relativity.

“And I couldn’t admit I didn’t know general relativity. I mean, here I had started this whole research program to study gravity and I tell them that I don’t know anything about general relativity. I didn’t . . . so okay, I had a major problem on my hands. And I had to be sort of a day ahead of the students. Now all of us have been caught out that way, but I had just been caught out. I couldn’t say no.

“So I teach this relativity course. Now, the reason why that figures in the LIGO story is because that’s where LI...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I had a terrible time with the mathematics. And I tried to do everything by making a Ged...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

You see, I was trying to learn it myself. I mean, in the process of learning it, the mathematics was beyond what I really underst...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“I gave as a problem, as a Gedanken problem, the idea, ‘Well, let’s measure gravitational waves by sending light beams between things,’ because that was something you could solve. The idea was that here was an object. You’d put another object here and make a right triangle of objects, floating freely in a vacuum. And we’d send light beams between them and then be able to figure out, ‘What does the gravitational wave do to the time it takes light to go between those things?’ It was a very stylized problem, like a haiku, you know? You’d never think that it was of any value.”

The idea: Suspend mirrors so they’re free to rock parallel to the earth and watch them toss on the passing gravitational wave. Keep track of the distance between them, and their motions will record the changing shape of spacetime. Since light’s speed is a constant, the time it takes for light to race the track

measures the length of the course. If the light travel time is a little longer, the distance between the mirrors has stretched. If the light travel time is a little shorter,...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Precision clocks are not good enough to distinguish minuscule varia...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Rai’s idea was to use the floating mirrors to build a far more precise instrument, an interferometer (the roots of the wo...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Instead of bouncing light along one arm, an interferometer sends light down two arms arranged in an L. Laser light is split into two beams, so that one beam travels along one arm of the L and the other travels along the orthogonal arm of the L. Each beam bounces off a mirror at the far end and returns down the respective arm to interfere back at the original apex. The recombined light is then split into two outputs. If the light travels the same distance in each direction, then the light in one output will recombine perfectly so that the output is bright. Light in the other output will combine

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Under the pressures of the war, incited by that urgency, technologies were constructed as suddenly as the building, if with higher production value.

The tense motivations produced some of the most crucial technological advances during the war—think radar and microwave engineering—and those were quickly integrated into the quotidian concerns of life during peacetime.

“No, no, the work wasn’t classified. The military was absolutely the most wonderful way to get money. Their mission at that time—and that’s something that’s grossly misunderstood by all the people that got into trouble with Vietnam and everything else—the military was in the business of training scientists.

They wanted not to get caught again the next time there was a need for a Manhattan Project or a Radiation Lab . . . and all they wanted to do was train good scientists, they didn’t give a goddamn what they were going to work on.”

A fully operational machine was off in a far future. He had no defense to the concern repeatedly vocalized: Maybe no astrophysical phenomena are calamitous enough to ring space and time loud enough.

Rai’s disadvantage was significant and,

he understood, essentially insurmountable. He couldn’t build the real thing, the full-scale machine, the ultimate recording device, the insane astronomical pinnacle of audio engineering.

He would watch while others made his haiku physical. He kept at it still, developing the instrumentation on the side, swapping students in and out of the ifo lab while succeeding on other experimental fronts. Rai began life with one ambition, high fidelity—“to make music easier to hear”—and that ambition was tie...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Rai says, “Then I met Kip. That’s the ne...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Wheeler’s intention was as much to learn the subject as to teach it, apparently a standard tactic for physics professors.

When challenged on the use of the atomic bomb, he would respond as he did in his autobiography: “One cannot escape the conclusion that an atomic bomb program started a year earlier and concluded a year sooner would have spared 15 million lives, my brother Joe’s among them.”

All of this hot energy keeps the star puffed out and highly pressurized so that total gravitational collapse is resisted. And this goes on for a very long time.

After a few billion years, when nuclear fusion is no longer energetically favorable, essentially when the star runs out of fuel in the form of light elements, the furnace cools and the outward pressure that kept the giant atmosphere aloft is no longer up to the task. The star begins to collapse under its own weight.

And then what? Wheeler believed the question of the end state of gravitational collapse to be the single most important outsta...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Gravity would crush a dying star, but the nuclear forces would resist the compression. Which force would win?

Stars like our Sun will die as white dwarfs, a cool sphere of degenerate matter comparable in size to the Earth, the pressure of densely packed electrons enough to resist total collapse.

Heavier dead stars will stably end as neutron stars, an even denser sphere of degenerate nuclear matter around 20 to 30 kilometers across, the pressure of densely packed neutrons enough to resist total collapse.

But the heaviest stars have no more recourse to nuclear pressures. Unhindered...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

In 1967, shortly after Oppenheimer’s death, Wheeler was searching for a term to describe the ultimate dead star during a lecture, tired of repeating “completely collapsed gravitational object,” and someone from the audience shouted, “How about black hole?”