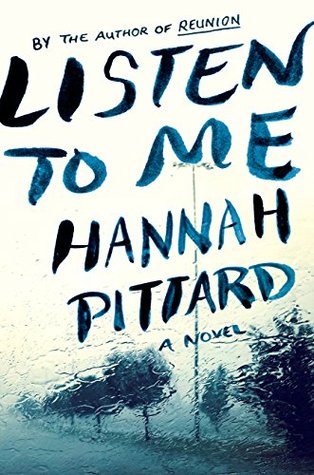

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But then, just three weeks ago—out of nowhere and with no warning whatsoever—the police appeared. They showed up at the front door of the apartment with pictures of a body, a coed who lived just down the street. They presented them to Maggie. Why had they let her see them?

“If he doesn’t go now, then we’ll die in Gary? Is that what you’re imagining?”

So it would be Maggie walking the dog on some street lined with tenements, and there would be no witnesses, and it would, quite matter-of-factly, be the ideal set of circumstances if, for instance, there were a carjacker lurking or a murderer or a rapist or one of those misfits in a ski mask.

then head off to the Tabard Inn, where he would have a late dinner and continue a recent flirtation with a bartender from Poland.

He assumed she’d been raised either in extreme poverty or extreme wealth.

She was wearing the robe. It was afternoon. It was daylight. Mark had a sudden sinking feeling that he was married to a loser.

But what was becoming more and more apparent—and this wasn’t a happy or an easy realization—was that Mark was spending his life with one of the world’s weaklings: the type of person who gets diagnosed with cancer and, instead of going outside and taking on life, gets in bed and waits for the inevitable. He’d expected more from Maggie. My god, he’d expected so much more!

His hope was to finish several chapters of his latest manuscript, a history of anonymity, which he believed—if pulled off correctly—might put him on the academic map in a major way.

She’d read all about it: his parents had kept him outside, in a cage. Bad things happened in Gary.

“If it’s my mom, do you mind taking it?” he said. “If you don’t want to, I completely understand.” The strange Ping-Pong of over-articulated etiquette was still in effect.

Robert and Gwen put money on everything. Sometimes it was funny. Sometimes it wasn’t. When they put money on Mark’s tenure, for instance, it was not funny at all that Robert had bet against.

Okay, sure, fine, yes. There was Elizabeth, his former research assistant. But they hadn’t touched. Not once!

“I’m fucking with you, Bucko.” The man laughed. “Just two guys joshing around. I like your wife. It’s a compliment.”

For one thing, she’d been wondering why he changed his password a few months ago. That question had most certainly been on her mind, but no way had she brought it up with him. There were too many obvious follow-up inquiries from Mark: How did she know he’d changed his password? Had she tried logging in to his personal account? His school account? Why?

“This is the story of a young woman who discovers her father has been videotaping her every time he rapes her, and it turns out she’s essentially famous in the world of Internet pedophilia. Like, the most famous molested girl in the world.”

And then for a half second—no, less than a half second, a nanosecond, a piece of time so fleeting there’s no way truly to prove it ever existed except through the memory of the thought—Maggie imagined the satisfaction she might feel if Gerome had a heat stroke and died. She imagined the permanent regret with which Mark would be forever saddled.

He knew he sounded frantic. Then, thinking perhaps of the wet child or the unsavory feel of the clerk’s hand on his or the idea of inbreeding and incest

It was draining sometimes, being always expected to be an equal in everything. She longed to be taken care of.

Most of his colleagues resisted the idea of an intelligence that could surpass their own. Of course, most of his colleagues were narcissists. They resisted the notion that artificial intelligence would ever be able to redesign itself of its own volition, and so obviously they rejected the possibility that it would eventually supersede humanity. Perhaps they were only a few weeks from finding out.

Videos had been discovered. There were dozens of young women, all students, and he’d secretly recorded his trysts with every one of them.

bleak little minute of irrational sadness,

The long and short of it, the plain and simple fact: Mark was afraid of technology and Maggie was afraid of people.

Or so the story went, which was all that mattered—the stories people told, because it was from the stories that they learned; it was in the past that they saw the future.