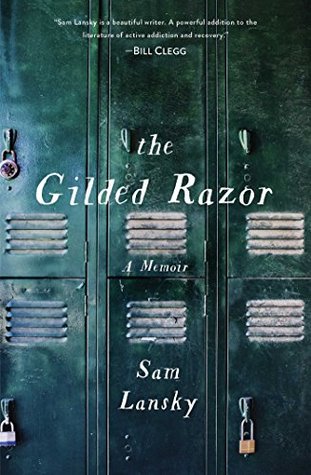

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It may not always get better, but it will always get different.

it was much easier obsessing than actually doing anything.

I empathized with the need for companionship that had prompted Jennifer to adopt the bird in the first place. It was the very same willingness to accept affection from inappropriate sources that I saw, and hated most, in myself.

I was not myself. I was someone who surged with confidence, someone fearless and bold.

When morning comes, I’ll be someone else. Someone different. Someone better.

I felt my grip starting to loosen. In a moment, I would fall. Or maybe, I thought, I would just fly.

Later, when it was time to apply to colleges, I chose Princeton not because I wanted to go to Princeton but because I wanted to be the kind of person who

could go to Princeton.

It was the final, essential component of the persona I had ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

any man who reminded me a little bit of my father—not so much that it felt transgressive but just enough that it felt like love.

so much that it felt transgressive but just enough that it felt like love.

I realized that I didn’t want to do this, but it also felt too late to say no. He had expectations of me. I didn’t want to disappoint him.

Maybe this was just how it was supposed to feel. The rush of anticipation, then a few minutes of intermittent pain and pleasure, and a big emptiness after.

You’re always looking for the next thing that you think will tell you who you’re supposed to be.”

I knew I hated him, but I didn’t know why. I didn’t know if I hated him because I believed he had turned me into a monster or because he couldn’t fix a monstrosity in me that was innate.

“You’re always enwrapped in a cloud of smoke. Literally, or metaphorically.”

I begged a God I did not believe in for a hurricane, a coyote attack, a wildfire, a nuclear holocaust—anything that might swallow the state of Utah and everything in it.

I was out of control—although privately I felt that it wasn’t my fault that he didn’t see my drug use as the only way I was able to maintain my control over the chaos of my life.

It was mine.

The people I had loved, if I was even capable of that. Maybe they were just people I had tricked into loving me.

And as I prayed, I felt a calm settling—not the presence of God, in whom I didn’t really believe, but the presence of some notional feeling that I wasn’t entirely alone out there after all.

When we were at camp, I stayed in my shelter, journaling. I cried several times a day. I prayed feverishly, begging anything that might resemble God to take my pain away. Over and over again in my notepad I wrote: “There is only clean, there is no in between,” a paraphrase of a line from an Elliott Smith song I had always loved but never really understood.

Real life was complicated, messy, unpredictable. Paradoxically, it was the natural world that felt artificial.

“There is only clean,” I whispered. “There is no in between.”

It seemed that as long as I stayed there, in that anesthetic inertia, the morbid reality of what was going on just a few miles north wouldn’t become real, wouldn’t end this bender on a sour note.

It hurt too much to respond, so I closed my computer. I crushed a tablet of morphine with my gilded razor and dissolved it into a bottle of chocolate milk.

I woke up every morning with a tunnel vision that I found perplexing but didn’t think to question. The only goal was to get high and change the way I felt, which was lonely and afraid.

I could readily acknowledge that something strange happened to my body when I put drugs and alcohol in it—I couldn’t help myself, I needed to be in an altered state all the time—but I was also certain that I was a fundamentally terrible person. Full of revulsion for who I had become, and yet helpless to behave any differently.

But I couldn’t see what he saw, the pattern of embarrassing mistakes and unfulfilled commitments that was starting to become so predictable.

Just so long as I didn’t have to admit that it was all my fault.

I said: “I’m grieving the loss of the person I thought I was supposed to be.”

It all stuck together in my mind, a hazy blur of self-fulfilling sickness. Clearheaded and sober, I still didn’t know why I did any of these things, things that I often did not want to do, feeling only that I must be carrying a fatal parasite, a brain tumor, or some satanic energy that wanted me dead and would stop at nothing until I had fatally self-destructed.

“What if you don’t say it’s the end?” she said. “What if it’s just the beginning of something new?”

The ship was flooding—I could see it—and there was only room on the life raft for me.

“You never have to go back there.” I heard people say this in meetings about their addictions, and it always confounded me. There was so much of me that had never really left. There was so much of me that I had lost there that I knew I could never get back.

At night, lying in bed with Michael, I had strange, vivid dreams where everything sparkled—a gilded razor, a mound of shimmering powder, a golden handgun that gleamed in the light. When I turned to look at my reflection in the mirror, there was glitter streaming from my nostrils, clinging to my lips, dripping from my chin. But then I would awaken to find sunshine pouring through the window, and I would turn to feel it on my face. After spending so much time in the darkness, my eyes had adjusted. It got easier over time, but there were still mornings where it was the most frightening thing—to

...more