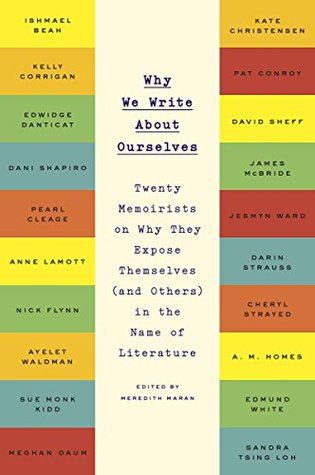

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

been a “self-chronicler”

from a very early age,

That said, I still fear (and loathe) being criticized for who I am, misunderstood, found wanting, accused of horrible things.

It’s different with my novels. They’re not literally me. In writing memoir, I’m opening myself to judgment of my life, not just my writing.

Rosie Schaap, who wrote the brilliant, beautiful memoir Drinking with Men, told me, “The only person who should look like an asshole in your memoir is you.”

everything is my own perception and nothing is presented as accusation or an ax to grind.

When I’m writing about myself, I write out of a strong urge not to protect myself. When I feel ego or self-justification or defensiveness creeping in or a wish to make myself look better than I was, I squelch it, if I can. It takes vigilance.

Don’t be afraid of writing into the heart of what you’re most afraid of. The story of a life lives in what you would rather not admit or say.

Memoir writing isn’t therapy—it’s better than therapy. It opens out your life to the world and lets the world in. Finding the

about the times she didn’t live up to her own high ideals.

I began to think that some of us are the designated rememberers. Why do we remember? I don’t know. But I think that’s why memoir interests us—because we’re the ones who pass the stories.

But then I read Ann Patchett’s memoir about her second marriage and thought, It’s doable; there’s a way.

something happens that compels me to do it—something that feels pressing and urgent,

also write memoir for the same reason I read memoirs; with the hope that my story might connect me with others. I write memoir to feel less alone.

When it’s fiction, it’s easier to accept public criticism. But when it’s memoir, they’re not talking about just a book. They’re also talking about your life.

People who are thinking of writing memoir should ask themselves where they would draw the line, whatever the line is. Would you feel comfortable exposing someone close to you to scrutiny that might change their entire lives? How much of yourself do you feel comfortable exposing?

Once you’ve written your no-holds-barred draft, your own series of rules about how far you’re willing to go should be part of the rewrite or revision process.

My Misspent Youth, 2001 Life Would Be Perfect If I Lived in That House, 2010 The Unspeakable, 2014

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, 2015

To me, a personal essay is a piece in which I use my own experiences as a lens to look at larger, more universal issues and phenomena.

During the writing, if it’s going well, I feel kind of pleasantly buzzed—anxious about finishing, worried that it’s no good but also, at times, undeservedly optimistic about its quality. After the writing, especially when it’s an early draft, I start wondering what my first readers are going to think. Like most writers, I show early versions of my work to a few people. And although these people almost always make useful, sometimes invaluable suggestions, it can be devastating when they don’t totally love the material right off the bat. I don’t think there’s a writer in the world for whom the

...more

try to soften any potential blows by implementing the old “be twice as hard on the narrator as you are on everyone else” trick.

I worry that someone will be angry, that I’ll violate a boundary, that I’ll get something wrong.

You’re setting out to do work that’s factual but also infused with acts of imagination. That doesn’t give you license to make stuff up, but it does mean you can use certain flourishes or stylistic techniques that are more common in fiction.

It is not, for the most part, a flattering portrait of my mother and it’s an even less flattering portrait of me.

For a relatively ordinary person like me, it helps to turn the volume up a notch or two—make yourself a little more neurotic, a little more intense, a little grouchier or more indignant.

Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life and Joyce Johnson’s Minor Characters,

They tell their personal stories in the context of very specific worlds that they are uniquely qualified to bring to you.

The Reenactments, 2013

try to come to the edge of what I know and push a little further over that edge. I think that any topic or scene or action that elicits any of the “lesser” emotions—shame, guilt, humiliation, etc.—is likely where the good stuff is lurking.

memoir is not simply stringing together the five or ten good stories you’ve been telling about your wacky childhood for your whole life. To cross the threshold into the deeper mysteries, you need to ask yourself why you’ve been telling those particular stories, and not the millions of others you could tell.

Not to play God with the world, but to observe it as clearly as possible, and then to allow my subjective inner world to filter what I believe I am seeing, to interpret it, as best I am able, in the hope that it might reveal something of my inner landscape.

her seventh novel, May We Be Forgiven, won the vaunted Baileys Women’s Prize (formerly the Orange Prize) for Fiction.

reconsider how one can live optimistically in a time that is inherently not optimistic.”

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=630006933&fref=ts

Write the most honest, truthful version of your story you can. That first draft is your draft. Don’t run away from whatever comes up for you when you do. Explore it.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/suemonkkidd

Before I made the leap, I grew so restless. I had so much unfulfilled longing, so much pent-up creativity. I was working part-time as an RN on a pediatric unit. I had two toddlers, a husband, a brick house, and a station wagon. There’s a line of poetry from Anne Sexton that I used as a chapter epigraph in The Dance of the Dissident Daughter: “One can’t build little white picket fences to keep the nightmares out.” It was sort of like that. On my thirtieth birthday, I was in the laundry room when it all seemed to come to a head. I remember dumping a bunch of diapers into the machine—this was

...more

“The role of a writer is not to say what we can all say, but what we are unable to say.”

maybe I should dump the idea. Maybe

It’s a process, and it usually starts in this place where I think it’s impossible. It’ll never happen! I’m overwhelmed! But then slowly, slowly, it starts to emerge.

But more than fifteen books later, I still struggle with the same feelings of self-worth, the same fear of failure, the same fears that I won’t be able to pull it off, that the well is running dry.

Publication hurts People in MFA programs think publishing is the pinnacle of creative success and esteem. It’s actually just the opposite. You have to go through it a few times before you realize how toxic, how sick, how crushing the whole thing can be even if a book does relatively well, let alone if it doesn’t.

I hate publication. It makes me extremely anxious. I can be at my most fragile for quite a long time, during that long, long period of waiting to see how a book is going to do. It’s an extremely painful part of the process. I get this feeling of grippage in my stomach before a book comes out. The easiest way not to have it is not to publish a lot more. I’m just too old for book tours. I’m sure you could find lots of people, like Margaret Atwood, who are a little older and they thrive on it. I don’t thrive on it. I’m wasted by it. I hate being away from my family and my life—my animals, my

...more

Sandra Tsing Loh I have just gotten off the phone with my friend and magazine editor, Ben. We have been talking about refinancing . . . It helps me to recall . . . the staid, rational person I was not too long ago: which is to say before I, a forty-something suburban mother, became involved in a wild and ill-considered extramarital affair. —Opening, The Madwoman in the Volvo, 2014

personal essays for The Atlantic

It was authentic, it assigned all the hypocrisy to me, rather than to others, and as a result, I think the book and show were both funnier and more persuasive because my character took the fall.

Atlantic pieces are long—four thousand words—so the inspiration is different than it is for shorter work. It’s like poetry, where you may ruminate and develop a lot of ideas but to get the opening and sustaining emotional pitch, drive, and obsession for the piece you have to wait for the heavens to open. It takes a while to wrap my arms around each one of these long-form essays.

When you’re a memoirist you have to keep writing your story—however not-ready-for-prime-time it is. I’m not a mystery writer. My material is my life.

When anybody tells a candid story of failure or sorrow, it tends to make the world bigger and safer for everyone.