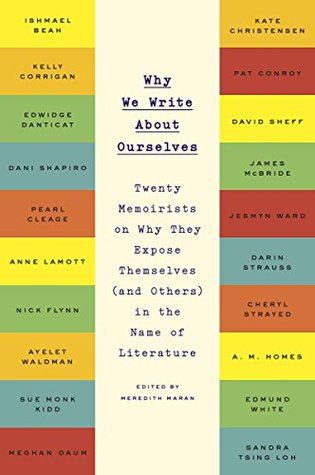

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 18 - January 24, 2023

As to my own privacy, I just wrote from how I thought about things as a child, in sort of a matter-of-fact way and unapologetically. I had to return to how I felt about things as a child, as a boy, not as the young man I had become by the time I wrote the book.

It isn’t possible to write about everything, and some things I needed to keep for my family and myself—the deepest intimacies of my emotions and experiences. My desire was to take moments of my life to make a point, and that is what I did.

Well, any sensible person would know that when several people experience the same event, they remember different aspects of that event. Still, all of their recollections would be truthful to what occurred.

It’s also immoral for the narrator to paint him- or herself in a saintly light. Of course, when you write about people, you always write your version of the truth about them. You write about how you see them, not how they view themselves. Otherwise they would be the authors.

In hindsight, I think my journal keeping was a colossal exercise in honing and developing my own point of view.

I want to yell, “Get out of there! Quit that job! Leave that guy! Get a new apartment! Speak up!” It’s a bit like watching a horror movie and wishing you could tell the girl not to go into the abandoned house alone at night, but of course she does it anyway.

My friend Rosie Schaap, who wrote the brilliant, beautiful memoir Drinking with Men, told me, “The only person who should look like an asshole in your memoir is you.” I strove to follow that. I hope I didn’t fail too badly.

In the memoir, and in an Elle magazine excerpt from the book, I went public with the truth about the math teacher who molested me in high school. As a result, my school launched an investigation into the rampant sexual abuse that was happening there in the late 1970s and early ’80s. I admitted to myself in the course of this process that I had been a victim. And as the truth came out, and everyone who wanted to talk about it on the record had a chance to, thirty-five years later, I resolved the trauma of those years.

It takes vigilance. Exposing myself is the only way to go, though. If I’d rather wear veils, I should write fiction. I write out of the sure knowledge that the more honest I am, the freer I am, and the freer I am, the happier I am.

Don’t be afraid of writing into the heart of what you’re most afraid of. The story of a life lives in what you would rather not admit or say.

I wondered if the journals were valuable only to me. But when I reread them, I felt that they were valuable not only as a purely personal document of one life but as evidence that, as Anaïs Nin said, one life, deeply examined, ripples out to touch all other lives.

When I’m writing about myself, I don’t worry about keeping secrets.

I have nothing to protect, which I think is crucial if you’re going to write autobiographically. If you’re going to write a memoir, you have to tell the truth as you know and remember it. Once you start smoothing your own rough edges, you might as well make it a novel.

Some of these relationships played important roles in my life, but those were also the only times in my life when I felt I was really not living up to my own understanding of what was honorable behavior.

Having an affair is always wrong because you are agreeing to lie to cover up your own bad behavior. Talking about those relationships didn’t make me look so good, but I wanted to show my own growth and development as a free woman who consciously committed to telling the truth about all things.

I’m very conscious of not telling other people’s secrets, or revealing things about people that would make them uncomfortable or unhappy in any way, because that’s not fair.

Ask yourself if you’re prepared to make yourself vulnerable and not care about people’s judgments. If you’re not yet who you want to be, keep working on your life and write about it later.

Don’t burn your journals. You might want those written recollections years from now when you’re ready to write your memoir.

I’d always wanted to tell the full story of my family, but I had to wait until my parents died.

I began to think that some of us are the designated rememberers. Why do we remember? I don’t know. But I think that’s why memoir interests us—because we’re the ones who pass the stories.

My sister Carol isn’t speaking to me. She wouldn’t speak to me at our mother’s funeral. She said we had a toxic family. I said, “No shit. I’ve been making a living off that toxic family my whole life.”

Here’s what I know: If a story is not told, it’s the silence around that untold story that ends up killing people. The story can open up a secret to the light.

Memoirs hurt people. Secrets hurt people. The question to ask yourself is, if you tell your story, will it do enough good to make it worth hurting people?

But in a novel, I can go anywhere. I can show the nastiest, most pitiful, regrettable sides of myself and everyone I know. I can expose every nerve. Consequently, I find it’s turning out to be much easier to write without the (understandable) boundaries memoir imposes.

There’s tremendous value in keeping the story and the themes in your subconscious mind.

Trust yourself. If you’ve remembered something very well—a fight, a kiss, a plane ride, a certain stranger—there’s a reason. Keep writing until you figure out the significance of your most vivid memories.

unborn. I also write memoir for the same reason I read memoirs; with the hope that my story might connect me with others. I write memoir to feel less alone.

To me, a personal essay is a piece in which I use my own experiences as a lens to look at larger, more universal issues and phenomena.

I’m also conscious of which stories are mine to tell and which stories belong to other people. If I tell a story involving someone else, I make sure to tell it from my point of view.

Walter Benjamin offers this, which perhaps says it better than I can: “It is half the art of storytelling to keep a story free from explanation as one reproduces it . . . The most extraordinary things, marvelous things, are related with the greatest accuracy, but the psychological connection of the events is not forced on the reader. It is left up to him to interpret things the way he understands them, and thus the narrative achieves an amplitude that information lacks.”

Mary Gaitskill quote should be pinned over the desk of anyone who is writing a memoir: “It’s not my job as an artist to tell you what to feel.”

I remember not knowing; first thinking something was very wrong, assuming it was death—someone had died. And then I remember knowing.

There’s no doubt in my mind that a writer knows when they’re making something up. You know when something’s a fact, when it happened, and when it isn’t.

Do we run away from subject matter because it causes controversy? My answer, as author and activist, is a definite no.

There’s a line of poetry from Anne Sexton that I used as a chapter epigraph in The Dance of the Dissident Daughter: “One can’t build little white picket fences to keep the nightmares out.” It was sort of like that.

I had a quote by Anaïs Nin that I’d kept on my desk while I was writing The Dance of the Dissident Daughter, and I dug it out and copied it for Ann, and we both kept it on our desks while we were writing Pomegranates. It reads, “The role of a writer is not to say what we can all say, but what we are unable to say.”

It is all hopeless. Even for a crabby optimist like me, things couldn’t be worse. Everywhere you turn, our lives and marriages and morale and government are falling to pieces. So many friends have broken children. The planet does not seem long for this world. Repent! Oh, wait, never mind. I meant: Help. —Opening, Help, Thanks, Wow, 2012

I thought it would be such a great thing to tell the truth about my mom, because my whole life had been about this made-up relationship, pretending I wasn’t mad about the damage she’d done to me.

In a family, that’s life threatening. They tell you that if you ever tell the truth about the family, the long bony hand will come out of the sky and kill you.

Everything that’s happened to you is all yours. Just write it. You can worry about the legal issues and the next bad holiday dinner later. Tell the story that’s in you to tell.

I think that kind of struggle is important for a writer. I think it’s a mistake for a writer to sit around coffee shops musing about bullshit. I think it’s a waste of time and I never do it.

A writer can’t be too negative. You have to have a little bit of innocence to be a good writer. Whatever you have to do to preserve that innocence—the “is that so?” element—you should do it. You can’t be someone who knows everything—“been there, done that.” If you know everything you shouldn’t be a writer. You should be God.

I still move around in circumstances where people don’t know who I am. Because I ain’t nobody, really. I’m still the same person.

You’re trying to share from a sense of humbleness. It’s almost like you’re asking forgiveness of the reader for being so kind as to allow you to indulge yourself at their expense.

The industry is accustomed to black writers writing about pain and struggle. I can think of a half-dozen white writers who write about the same things and never had to deal with being marginalized. They’re just seen as writers, period.

We’re writing memoirs 140 characters at a time, which means we’re basically writing nothing. If you’re writing nothing maybe you’re living nothing. Before you put your story down, first change the manner in which you’re living.

Sylvia Boorstein told me, “You’ve written a book about what you know now.” The idea being, that’s all we can do. We’ll know more later. That’s always true for a writer, but it’s truest of memoir. Sometimes I think the perfect life’s work for a memoirist might be to write the same book every ten years.

Part of the way I’ve always survived hard stuff is to write. So when Nic was addicted, when I didn’t know where he was or what he was doing or whether he was dead or alive, I got through long nights writing, writing, writing.

That’s why I decided to write the memoir. When we suffer trauma, we need to know that we aren’t alone. And we aren’t.

That piece also came from a place of pain. I was struggling to understand more deeply a personal situation that also affects many other people. Divorcing parents rationalize the trauma we inflict on our kids.