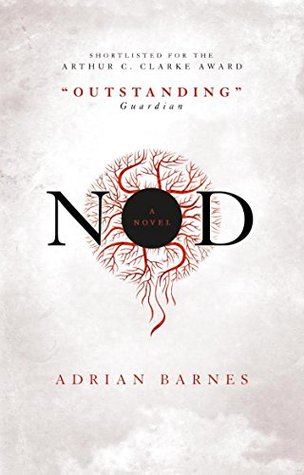

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I marvel at people who dared wear white. Did they think that the world wouldn’t touch them?

And then the cone explodes with a yawn—like the world is ending, not with a bang or a whimper, but an early bedtime. The sheets of glass don’t shatter, they disassemble and drift off into a burning blue sky. Then slowly, I turn toward the library. Everything is floating: trees, people, benches, windows, walls. The pavement beneath my feet gives way, and I tumble into space. The clock tower follows suit, its massive black hands wheeling off in different directions. Then everything fades until all that’s left is the sky and me. My body dissolves next and the sky becomes an all-encompassing

...more

If there is a God, then why isn’t the presence of His hand acknowledged in everything? Why do we only drag God in when something cool happens

There’s something holy about the face of a child weathering adult storms;

It was so odd to realize that choice had been a burden I’d been lugging around all my life—and that choice had only really existed because, until now, nothing particularly important had been at stake.

They’d been rich, they’d been poor. They’d been young and old, but now they were all the same in their greasiness

Eternity is right now.

Hell is time, isn’t that obvious? Take your greatest pleasure or your greatest fantasy and let it come continuously true—for a day, a week, a year, a decade. And that’s hell.

And still existence persisted.

There’s a natural point in the development of any religion where the prophet becomes first a nuisance and then a positive liability. Just imagine Jesus walking into an evangelical church while the collection plate was being passed around—or into a Catholic priest’s chamber while the altar boy’s frock is pulled up over his head. At some point it’s inevitable that the prophet has to go. When you stop and think about it, that’s the take-home message of the entire New Testament: off the prophet.

Children are the eternal, silent witnesses to every human sin, and the more we tatter their purity, the more we extol the clean white blouses of ‘innocence

‘Tell me who to pray to.’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Is it death?’ he asked. ‘What?’ ‘The dream. Do you think the dream is death?’ ‘I don’t know.’ Brandon looked up at me and smiled. ‘You’ve got to laugh. If it’s death, then it’s okay. If the dream is death, then we’re safe. I hope it’s death. I hope I die. I’m ready to die.’’

There isn’t much distance, once you’re forced to think about it, between a smile and a grimace of terror.

Someone once said that we get more difficult to love with each passing year because, over time, our histories grow so tangled that newcomers can no longer bushwhack their way into the thicketed and overgrown depths of our hearts.

Real romantics are never the ones with the easy, winning ways about them; the real romantics are always the guarded ones, the paranoid and the worried, the ones with furrowed brows and coffee jitters. After all, anybody looking with open eyes at the world we’d made would have to have been very, very worried.

Amorphous: that’s amore, always morphing.

Nobody says these things—it’s against the rules—but deep inside we know that we are, each of us, unknowable and ultimately alone, even when we love.