More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 1 - September 18, 2020

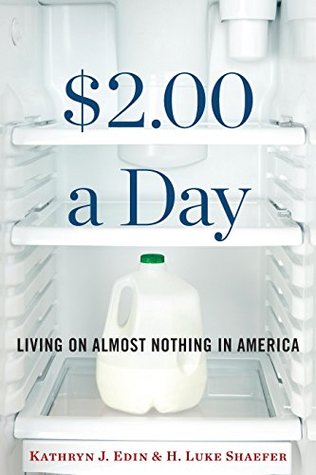

poverty among households with children had been on the rise since the nation’s landmark welfare reform legislation was passed in 1996—and at a distressingly fast pace. As of 2011, the number of families in $2-a-day poverty had more than doubled in just a decade and a half.

The government’s emphasis on personal responsibility must be matched by bold action to expand access to, and improve the quality of, jobs.

In 1996, welfare reform did away with a sixty-year-old program that entitled families with children to receive cash assistance as long as they had economic need. It was replaced with a new welfare program, called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)—the

And since the American public deemed divorced or never-married mothers less deserving than widows, many states initiated practices intended to keep them off the rolls.

More programs targeting poor families were passed as part of Johnson’s Great Society and its War on Poverty than at any other time in American history.

Although there is little evidence to support such a claim, welfare is widely believed to engender dependency.

Sometimes evidence, however, doesn’t stand a chance against a compelling narrative.

Beginning in 2004, public schools were mandated to count the number of homeless children in their classrooms. (This is the number of children whose parents or guardians could not afford permanent housing but were still attending school.) In 2004–2005, there were 656,000 such children. This number spiked temporarily in 2005–2006 because of Hurricanes Katrina and Wilma, but then gradually increased over time, reaching 795,000 in 2007–2008 and 1.3 million in 2013–2014.

the way things turned out, the 1996 reformers didn’t merely “replace” welfare. They killed it.

Yet her appearance undoubtedly put her at a disadvantage. Her smile revealed badly decayed teeth and stained gums, while her glasses, missing a temple, sat askew on her nose.

Nor did she seem to mind that Jennifer’s address, “c/o La Casa,” marked her as homeless.

A willingness to work hard for little pay was all this occupation required,

minority homeowners, often victims of predatory lending practices by some of the biggest names in banking, had been badly affected by the foreclosure crisis.

Yet even when working full-time, these jobs often fail to lift a family above the poverty line.

How is it that a solid work ethic is not an adequate defense against extreme poverty?

Yet laying the blame on a lack of personal responsibility obscures the fact that there are powerful and ever-changing structural forces at play here.

Service sector employers often engage in practices that middle-class professionals would never accept. They adopt policies that, purposely or not, ensure regular turnover among their low-wage workers, thus cutting the costs that come with a more stable workforce, including guaranteed hours, benefits, raises, promotions, and the like. Whatever can be said about the characteristics of the people who work low-wage jobs, it is also true that the jobs themselves too often set workers up for failure.

the routine of going to work each day can be the single biggest stabilizing force in their otherwise chaotic lives.

and their kin pull them down as often as they lift them up.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) deems a family that is spending more than 30 percent of its income on housing to be “cost burdened,” at risk of having too little money for food, clothing, and other essential expenses.

Today there is no state in the Union in which a family that is supported by a full-time, minimum-wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent without being cost burdened, according to HUD.

While living with relatives sometimes offers strength and uplift, it can also prove toxic for the most vulnerable in our society, ending in sexual, physical, or verbal abuse.

At some point, if the authorities were to find out that Kaitlin and Cole were sharing a room, Jennifer would be at risk of losing custody due to “neglect.”

By today’s standards of child well-being, Jennifer can’t move into a studio apartment to help balance her family’s budget.

Only about a quarter of income-eligible families get any kind of rental subsidy.

In 2011, a smaller fraction of Americans received any sort of rental assistance from the government than was the case two decades earlier. And twenty years ago, the need was not nearly as great.

In the United States, housing assistance is not an entitlement—families are not legally guaranteed help just because their incomes are low.

Families in $2-a-day poverty who must double up with friends or relatives sometimes find themselves in a perfect storm of risk for sexual, emotional, or physical abuse.

Exposure to toxic stress affects people mentally and even physically. It can impair “executive functions, such as decision-making, working memory, behavioral self-regulation, and mood and impulse control.” It “may result in anatomic changes and/or physiologic dysregulations that are the precursors of later impairments in learning and behavior as well as the roots of chronic, stress-related physical and mental illness.” Toxic stress can literally wear you down and, in the end, kill you.

Trauma and the reverberations of toxic stress ripple through generations, from parent to child, sometimes even grandparent to parent to child.

Survival strategies come in three forms. The first is taking advantage of public spaces and private charities—the nation’s libraries, food pantries, homeless shelters, and so on. Then come a variety of income-generation strategies, such as donating plasma—means for gleaning at least some of that all-important resource that families seem unable to survive without: cash. Finally, there’s the art—often finely honed through years of hardship—of finding ways to stretch your resources and make do with less.

Places like the public library where Jennifer, Kaitlin, and Cole found refuge are crucial to the day-to-day survival strategies of the $2-a-day poor. They offer a warm place to sit, a clean and safe bathroom, and a way to get online to complete a job application. They provide free educational programs for kids. Perhaps most important, they can help struggling families feel they are part of society instead of cast aside by it.

Sometimes these institutions serve those in need begrudgingly—a library might prefer that it not be a rest stop and warming station for the city’s homeless people. But other times they attend to destitute patrons with tremendous love and warmth.

Private charity is a complement to government action, something that bolsters the government safety net.

Some shelters can feel quite unsafe to a vulnerable mother and child with nowhere else to go, especially to those with a history of victimization.

good reasons for such policies—often they are a requirement of the funding they receive, or simply a response to short supply given the demand (too many homeless families and too few beds)—a few months is a very short time for any family with no resources to become self-sufficient.

As a result, those experiencing a spell of $2-a-day poverty are liable to find themselves in a never-ending hunt for the next place to live, making it even harder for them to find and keep a job.

For the $2-a-day poor, America’s private charities are the difference between shelter and no shelter, a meal and no meal, a new backpack for school and none at all. And yet they can provide only an incomplete patchwork of aid, with numerous holes.

while SNAP may stave off some hardship, it doesn’t help families exit the trap of extreme destitution like cash might.

Even if you are among the lucky few to be awarded a rent subsidy, claim government health insurance, and enroll in SNAP—even if you get every in-kind benefit our society might provide—you still lack the $20 in cash to buy an outfit from Goodwill to wear to that job interview, or to pay the bus fare to get downtown.

When the new poverty of those living on $2 a day meets the old poverty of long-term economic stagnation, a whole region can become starved of cash. In places like the Delta, the bite of $2-a-day poverty is experienced on a community level.

At its best, it forges bonds of interdependence that inspire the slightly better-off to aid those who are struggling in ways that speak to the marvel of human goodness. But at its worst, when the new poverty meets the old, it warps human relationships and puts those at the very bottom of society in a position that is ripe for exploitation.

What happens when a community starved for cash forges a shadow economy that threatens to overtake the formal one—and the two become commingled, almost indistinguishable from each other? Does it become that much harder for a community to right its collective course, to return to a formal system with rules by which people play? The old poverty was linked to an economy based on exploitation of the worst sort.

And a place that has experienced entrenched poverty for decades has met a new poverty of the deepest sort.

Those trading SNAP for cash might be able to keep the lights and heat on, but doing so virtually guarantees that someone—probably everyone—in the house will go hungry. Hunger, in turn, may put mothers and children at risk of demeaning and dangerous sexual liaisons. To put it simply, not having cash basically ensures that you have to break the law and expose yourself to humiliation in order to survive.

He made the case that four values were especially important: the “autonomy of the individual,” the “virtue of work,” the “primacy of the family,” and the “desire for and sense of community.” The old welfare system was portrayed, if unfairly, as supporting the opposite—indolence and single parenthood.

The old welfare system separated its claimants from the mainstream. It may even have created a class of outcasts forced to trade their sense of citizenship for relief.

The ultimate litmus test we endorse for any reform is whether it will serve to integrate the poor—particularly the $2-a-day poor—into society. It is not enough to provide material relief to those experiencing extreme deprivation. We need to craft solutions that can knit these hard-pressed citizens back into the fabric of their communities and their nation.

Our approach to ending $2-a-day poverty is guided by three principles: (1) all deserve the opportunity to work; (2) parents should be able to raise their children in a place of their own; and (3) not every parent will be able to work, or work all of the time, but parents’ well-being, and the well-being of their children, should nonetheless be ensured.

Government-subsidized private sector job creation is one way forward.