More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 10 - December 19, 2020

The best reason I have come up with for looking closely into Rwanda’s stories is that ignoring them makes me even more uncomfortable about existence and my place in it. The horror, as horror, interests me only insofar as a precise memory of the offense is necessary to understand its legacy.

I just looked, and I took photographs, because I wondered whether I could really see what I was seeing while I saw it,

They may think that they didn’t kill because they didn’t take life with their own hands, but the people were looking to them for their orders. And, in Rwanda, an order can be given very quietly.”

in Rwanda during the months of extermination the kettles of buzzards, kites, and crows that boiled over massacre sites marked a national map against the sky, flagging the “no-go” zones for people like Samuel and Manase, who took to the bush to survive.

the whooping we’d heard was a conventional distress signal and that it carried an obligation. “You hear it, you do it, too. And you come running,” he said. “No choice. You must. If you ignored this crying, you would have questions to answer. This is how Rwandans live in the hills.”

This is in a country that didn’t have a single person with a bachelor’s degree in 1960.

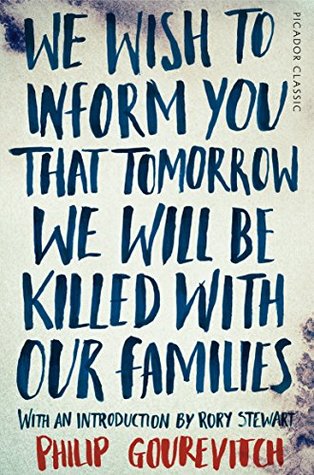

Our dear leader, Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, How are you! We wish you to be strong in all these problems we are facing. We wish to inform you that we have heard that tomorrow we will be killed with our families. We therefore request you to intervene on our behalf and talk with the Mayor. We believe that, with the help of God who entrusted you the leadership of this flock, which is going to be destroyed, your intervention will be highly appreciated, the same way as the Jews were saved by Esther. We give honor to you.

So Rwandan history is dangerous. Like all of history, it is a record of successive struggles for power, and to a very large extent power consists in the ability to make others inhabit your story of their reality—even, as is so often the case, when that story is written in their blood.

This was all strictly run-of-the-mill Victorian patter, striking only for the fact that a man who had so exerted himself to see the world afresh had returned with such stock observations. (And, really, very little has changed; one need only lightly edit the foregoing passages—the crude caricatures, the question of human inferiority, and the bit about the baboon—to produce the sort of profile of misbegotten Africa that remains standard to this day in the American and European press, and in the appeals for charity donations put out by humanitarian aid organizations.)

This made sense to me. We are, each of us, functions of how we imagine ourselves and of how others imagine us, and, looking back, there are these discrete tracks of memory: the times when our lives are most sharply defined in relation to others’ ideas of us, and the more private times when we are freer to imagine ourselves. My own parents and grandparents came to the United States as refugees from Nazism. They came with stories similar to Odette’s, of being hunted from here to there because they were born as a this and not a that, or because they had chosen to resist the hunters in the service

...more

Power is terribly complex; if powerful people believe in demons it may be best not to laugh at them.

Genocide, after all, is an exercise in community building. A vigorous totalitarian order requires that the people be invested in the leaders’ scheme, and while genocide may be the most perverse and ambitious means to this end, it is also the most comprehensive. In 1994, Rwanda was regarded in much of the rest of the world as the exemplary instance of the chaos and anarchy associated with collapsed states. In fact, the genocide was the product of order, authoritarianism, decades of modern political theorizing and indoctrination, and one of the most meticulously administered states in history.

...more

Killing Tutsis was a political tradition in postcolonial Rwanda; it brought people together.

The people were the weapon, and that meant everybody: the entire Hutu population had to kill the entire Tutsi population. In addition to ensuring obvious numerical advantages, this arrangement eliminated any questions of accountability which might arise. If everybody is implicated, then implication becomes meaningless. Implication in what? A Hutu who thought there was anything to be implicated in would have to be an accomplice of the enemy.

“In a war,” he told me, “you can’t be neutral. If you’re not for your country, are you not for its attackers?”

“Personally, I don’t believe in the genocide. This was not a conventional war. The enemies were everywhere. The Tutsis were not killed as Tutsis, only as sympathizers of the RPF.” I wondered if it had been difficult to distinguish the Tutsis with RPF sympathies from the rest. Mbonampeka said it wasn’t. “There was no difference between the ethnic and the political,” he told me. “Ninety-nine percent of Tutsis were pro-RPF.” Even senile grandmothers and infants? Even the fetuses ripped from the wombs of Tutsis, after radio announcers had reminded listeners to take special care to disembowel

...more

By regarding the genocide, even as he denied its existence, as an extension of the war between the RPF and the Habyarimana regime, Mbonampeka seemed to be arguing that the systematic state-sponsored extermination of an entire people is a provokable crime—the fault of the victims as well as the perpetrators. But although the genocide coincided with the war, its organization and implementation were quite distinct from the war effort.

A councilwoman in one Kigali neighborhood was reported to have offered fifty Rwandan francs apiece (about thirty cents at the time) for severed Tutsi heads, a practice known as “selling cabbages.”

In discussions of us-against-them scenarios of popular violence, the fashion these days is to speak of mass hatred. But while hatred can be animating, it appeals to weakness. The “authors” of the genocide, as Rwandans call them, understood that in order to move a huge number of weak people to do wrong, it is necessary to appeal to their desire for strength—and the gray force that really drives people is power. Hatred and power are both, in their different ways, passions. The difference is that hatred is purely negative, while power is essentially positive: you surrender to hatred, but you

...more

Take the best estimate: eight hundred thousand killed in a hundred days. That’s three hundred and thirty-three and a third murders an hour—or five and a half lives terminated every minute. Consider also that most of these killings actually occurred in the first three or four weeks, and add to the death toll the uncounted legions who were maimed but did not die of their wounds, and the systematic and serial rape of Tutsi women—and

“The only thing alive was the wind, except at the roadblocks, and the roadblocks were everywhere.

“What could I do?” he said, when I asked him about the eighty-two dead Tutsi schoolchildren at Kibeho.

“the Vatican is too strong, and too unapologetic for us to go taking on bishops. Haven’t you heard of infallibility?”

. . . and it might well happen to most of us dainty people that we were in the thick of the battle of Armageddon without being aware of anything more than the annoyance of a little explosive smoke and struggle on the ground immediately about us. —GEORGE ELIOT Daniel Deronda

Even the blue-helmeted soldiers of UNAMIR were shooting dogs on sight in the late summer of 1994. After months, during which Rwandans had been left to wonder whether the UN troops knew how to shoot, because they never used their excellent weapons to stop the extermination of civilians, it turned out that the peacekeepers were very good shots. The genocide had been tolerated by the so-called international community, but I was told that the UN regarded the corpse-eating dogs as a health problem.

if it was a genocide, the Convention of 1948 required the contracting parties to act. Washington didn’t want to act. So Washington pretended that it wasn’t a genocide. Still, assuming that the above exchange took about two minutes, an average of eleven Tutsis were exterminated in Rwanda while it transpired.

IN SEPTEMBER OF 1997, shortly before Secretary-General Kofi Annan muzzled him against testifying before the Belgian Senate, General Dallaire, formerly of UNAMIR, went on Canadian television and said of his tour in Rwanda: “I’m fully responsible for the decisions of the ten Belgian soldiers dying, of others dying, of several of my soldiers being injured and falling sick because we ran out of medical supplies, of fifty-six Red Cross people being killed, of two million people becoming displaced and refugees, and about a million Rwandans being killed—because the mission failed, and I consider

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Rwanda had presented the world with the most unambiguous case of genocide since Hitler’s war against the Jews, and the world sent blankets, beans, and bandages to camps controlled by the killers, apparently hoping that everybody would behave nicely in the future. The West’s post-Holocaust pledge that genocide would never again be tolerated proved to be hollow, and for all the fine sentiments inspired by the memory of Auschwitz, the problem remains that denouncing evil is a far cry from doing good.

ON TELEVISION, MAJOR General Dallaire was politic. He blamed no governments by name. He said, “The real question is: What does the international community really want the UN to do?” He said, “The UN simply wasn’t given the tools.” And he said, “We did not want to take on the Rwandan armed forces and the interahamwe.” Listening to him, I was reminded of a conversation I had with an American military intelligence officer who was having a supper of Jack Daniel’s and Coca-Cola at a Kigali bar. “I hear you’re interested in genocide,” the American said. “Do you know what genocide is?” I asked him to

...more

power largely consists in the ability to make others inhabit your story of their reality, even if you have to kill a lot of them to make that happen. In this raw sense, power has always been very much the same everywhere; what varies is primarily the quality of the reality it seeks to create: is it based more in truth than in falsehood, which is to say, is it more or less abusive of its subjects? The answer is often a function of how broadly or narrowly the power is based: is it centered in one person, or is it spread out among many different centers that exercise checks on one another? And

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Conrad’s Marlow said of England, “We live in the flicker—may it last as long as the old earth keeps rolling! But darkness was here yesterday.”

The piled-up dead of political violence are a generic staple of our information diet these days, and according to the generic report all massacres are created equal: the dead are innocent, the killers monstrous, the surrounding politics insane or nonexistent. Except for the names and the landscape, it reads like the same story from anywhere in the world:

The horror becomes absurd.

In the words of Amnesty International: “Whatever the scale of atrocities committed by one side, they can never justify similar atrocities by the other.” But what does the word “similar” mean in the context of a genocide? An atrocity is an atrocity and is by definition unjustifiable, isn’t it? The more useful question is whether atrocity is the whole story. Consider General Sherman’s march through Georgia at the head of the Union Army near the end of the American Civil War, a scorched-earth campaign of murder, rape, arson, and pillage that stands as a textbook case of gross human rights abuses.

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I said that I was resistant to the very idea of leaving bodies like that, forever in their state of violation—on display as monuments to the crime against them, and to the armies that had stopped the killing, as much as to the lives they had lost. Such places contradicted the spirit of the popular Rwandan T-shirt: “Genocide. Bury the dead, not the truth.” I thought that was a good slogan, and I doubted the necessity of seeing the victims in order fully to confront the crime. The aesthetic assault of the macabre creates excitement and emotion, but does the spectacle really serve our

...more

When the first wave of shooting began, Alexandre had been at Zambatt, and he said: “I remember there were thousands of people crushing into the parking area. Thousands and thousands of people. I was up on the roof, watching. And I saw this one woman, a fat woman. In thousands and thousands and thousands of people, this one fat woman was the only thing I saw. I didn’t see anyone else. They were just thousands. And this fat woman, pressing along with the crowd—while I watched she was like a person drowning.” Alexandre brought his hands together, making them collapse inward and sink, and he

...more

For Alexandre, all of Kibeho had come down to one fat woman in a yellow blouse drowned by the thousands and thousands of others. “After the first death there is no other,” wrote Dylan Thomas, in his World War II poem “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London.” Or, as Stalin, who presided over the murders of at least ten million people, calculated it: “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” The more the dead pile up, the more the killers become the focus, the dead only of interest as evidence.

What distinguishes genocide from murder, and even from acts of political murder that claim as many victims, is the intent. The crime is wanting to make a people extinct. The idea is the crime. No wonder it’s so difficult to picture. To do so you must accept the principle of the exterminator, and see not people but a people.

Nobody wants to know.” Odette nodded at my notebook, where I was writing as she spoke. “Do the people in America really want to read this? People tell me to write these things down, but it’s written inside of me. I almost hope for the day when I can forget.”

I had the impression that Rwandans often spoke two languages—not just Kinyarwanda and French or English, but one language among themselves and an entirely different language with outsiders. By way of an example, I said that I had talked with a Rwandan lawyer who had described the difficulty of integrating his European training into his Rwandan practice. He loved the Cartesian, Napoleonic legal system, on which Rwanda’s is modeled, but, he said, it didn’t always correspond to Rwandan reality, which was for him an equally complete system of thought. By the same token, when this lawyer spoke with

...more

This was one of the great mysteries of the war about the genocide: how, time and again, international sympathy placed itself at the ready service of Hutu Power’s lies. It was bewildering enough that the UN border camps should be allowed to constitute a rump genocidal state, with an army that was regularly observed to be receiving large shipments of arms and recruiting young men by the thousands for the next extermination campaign. And it was heartbreaking that the vast majority of the million and a half people in those camps were evidently at no risk of being jailed, much less killed, in

...more

Even if not taking sides were a desirable position, it is impossible to act in or on a political situation without having a political effect.

ACCORDING TO ITS mandate, the UNHCR provides assistance exclusively to refugees—people who have fled across an international border and can demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution in their homeland—and fugitives fleeing criminal prosecution are explicitly disqualified from protection. The mandate also requires that those who receive UNHCR’s assistance must be able to prove that they are properly entitled to refugee status. But no attempt was ever made to screen the Rwandans in the camps; it was considered far too dangerous. In other words, we—all of us who paid taxes in countries that

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

an alarming number of Western commentators took cynical solace in the conviction that this state of affairs was about as authentic as Africa gets. Leave the natives to their own devices, the thinking went, and—Voilà!— Zaire. It was almost as if we wanted Zaire to be the Heart of Darkness; perhaps the notion suited our understanding of the natural order of nations.

Father Victor, the Mokoto monk, told me in Goma. “All these organizations—they will give blankets, food, yes. But save lives? No, they can’t.”

The world powers made it clear in 1994 that they did not care to fight genocide in central Africa, but they had yet to come up with a convincing explanation of why they were content to feed it.

Colonel Joseph Karemera, Rwanda’s Minister of Health, asked me, “When the people receiving humanitarian assistance in those camps come and kill us, what will the international community do—send more humanitarian assistance?”

Never before in modern memory had a people who slaughtered another people, or in whose name the slaughter was carried out, been expected to live with the remainder of the people that was slaughtered, completely intermingled, in the same tiny communities, as one cohesive national society.