More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Several things have happened to undermine this division of labor.

First,

Second,

Third,

The time has come for new ways of telling true stories beyond civilizational first principles. Without Man and Nature, all creatures can come back to life,

How else can we account for the fact that anything is alive in the mess we have made?

The chapters build an open-ended assemblage, not a logical machine; they gesture to the so-much-more out there.

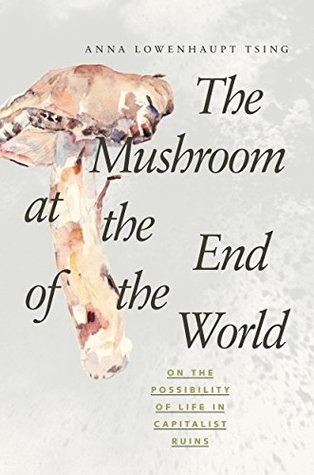

I use images to present the spirit of my argument rather than the scenes I discuss.

Imagine “first nature” to mean ecological relations (including humans) and “second nature” to refer to capitalist transformations of the environment.

My book then offers “third nature,” that is, what manages to live despite capitalism.

we must evade assumptions that the future is that singular direction ahead.

Like virtual particles in a quantum field, multiple futures pop in and out of possibility; third nature emerges...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Yet progress stories have ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

matsutake seasons

All books emerge from similarly hidden collaborations.

This book emerged from the work of the Matsutake Worlds Research Group:

our group convened to explore a new anthropology of always-in-process collaboration.

research categories

develop with the research, not before

Consider it an adventure story in which the plot unfolds from one book to the next.

Multispecies storytelling was one of our products.

inspired my interest in knowing capitalism beyond its heroic reifications.

as did study groups at the University of Toronto (where I was invited by Tania Li) and at the University of Minnesota (where I was invited by Karen Ho).

I feel privileged to have had a short moment of encouragement from Julie Graham before her death.

The “economic diversity” perspective that she pioneered with Kathryn Gibson helped not ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The final work on the book overlapped with the beginning of the Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene project, funded by the Danish National Research Foundation.

Yet, to protect people’s privacy, most individual names in the book are pseudonyms.

The exceptions are public figures, including scientists as well as those who offer their views in public spaces.

A similar intention shapes my use of place names: I name cities but, because this book is not primarily a village study, I avoid local place names when I move to the countryside, wher...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

WHAT DO you DO WHEN YOUR WORLD STARTS TO FALL apart?

The world’s climate is going haywire, and industrial progress has proved much more deadly to life on earth than anyone imagined a century ago. The economy is no longer a source of growth or optimism; any of our jobs could disappear with the next economic crisis.

Precarity once seemed the fate of the less fortunate. Now it seems that all our lives are precarious—even when, for the moment, our pockets are lined.

This book tells of my travels with mushrooms to explore indeterminacy and the conditions of precarity, that is, life without the promise of stability.

This book is not a critique of the dreams of modernization and progress that offered a vision of stability in the twentieth century; many analysts before me have dissected those

dreams. Instead, I address the imaginative challenge of living without those handrails,

the curiosity that seems to me the first requirement of collaborative survival in precarious times.

Grasping the atom was the culmination of human dreams of controlling nature. It was also the beginning of those dreams’ undoing. The bomb at Hiroshima changed things.

This awareness only increased as we learned about pollution, mass extinction, and climate change.

Hiroshima’s bomb also opened the door to the other half of today’s precarity: the surprising contradictions of postwar

development.

On the one hand, no place in the world is untouched by that global political economy built from the postwar development apparatus.

Modernization was supposed to fill the world—both communist and capitalist—with jobs, and not just any jobs but “standard employment” with stable wages and benefits. Such jobs are now quite rare; most people depend on much more irregular livelihoods. The irony of our times, then, is that everyone depends on capitalism but almost no one has what we used to call a “regular job.” To live with precarity requires more than railing at those who put us here (although that seems useful too, and I’m not against it). We might look around to notice this strange new world, and we might stretch our

...more

We might look around to notice this strange new world, and we might stretch our imaginati...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Matsutake are wild mushrooms that live in human-disturbed forests.

To follow matsutake guides us to possibilities of coexistence within environmental

disturbance.

Matsutake also illuminate the cracks in the global political economy.

Matsutake commerce, however, hardly leads to twentieth-century development dreams.

Commercial wild-mushroom picking is an exemplification of precarious livelihood, without security.

This book takes up the story of precarious livelihoods and precarious environments through tracking matsutake commerce and ecology.