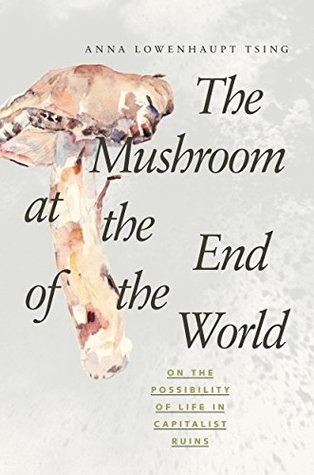

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 13 - December 10, 2019

Imagine “first nature” to mean ecological relations (including humans) and “second nature” to refer to capitalist transformations of the environment.

“third nature,” that is, what manages to live despite capitalism.

Mushrooms pull me back into my senses, not just—like flowers—through their riotous colors and smells but because they pop up unexpectedly, reminding me of the good fortune of just happening to be there.

When Hiroshima was destroyed by an atomic bomb in 1945, it is said, the first living thing to emerge from the blasted landscape was a matsutake mushroom.

To follow matsutake guides us to possibilities of coexistence within environmental disturbance.

How might capitalism look without assuming progress? It might look patchy: the concentration of wealth is possible because value produced in unplanned patches is appropriated for capital.

Indeed, human disturbance allowed Tricholoma matsutake to emerge in Japan. This is because its most common host is red pine (Pinus densiflora), which germinates in the sunlight and mineral soils left by human deforestation.

This is a story we need to know. Industrial transformation turned out to be a bubble of promise followed by lost livelihoods and damaged landscapes. And yet: such documents are not enough. If we end the story with decay, we abandon all hope—or turn our attention to other sites of promise and ruin, promise and ruin.

The most convincing Anthropocene time line begins not with our species but rather with the advent of modern capitalism, which has directed long-distance destruction of landscapes and ecologies.

Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable encounters transform us; we are not in control, even of ourselves. Unable to rely on a stable structure of community, we are thrown into shifting assemblages, which remake us as well as our others.

Even when disguised through other terms, such as “agency,” “consciousness,” and “intention,” we learn over and over that humans are different from the rest of the living world because we look forward—while other species, which live day to day, are thus dependent on us.

As long as we imagine that humans are made through progress, nonhumans are stuck within this imaginative framework too.