More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

March 9 - April 18, 2020

The time has come for new ways of telling true stories beyond civilizational first principles. Without Man and Nature, all creatures can come back to life, and men and women can express themselves without the strictures of a parochially imagined rationality.

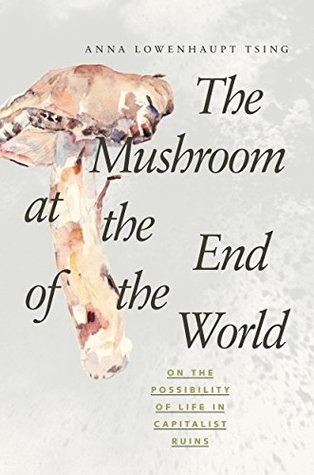

This book tells of my travels with mushrooms to explore indeterminacy and the conditions of precarity, that is, life without the promise of stability.

the uncontrolled lives of mushrooms are a gift—and a guide—when the controlled world we thought we had fails.

Despite talk of sustainability, how much chance do we have for passing a habitable environment to our multispecies descendants?

Matsutake are wild mushrooms that live in human-disturbed forests.

To follow matsutake guides us to possibilities of coexistence within environmental disturbance.

Many matsutake foragers are displaced and disenfranchised cultural minorities. In the U.S. Pacific Northwest, for example, most commercial matsutake foragers are refugees from Laos and Cambodia.

This book takes up the story of precarious livelihoods and precarious environments through tracking matsutake commerce and ecology.

As long as authoritative analysis requires assumptions of growth, experts don’t see the heterogeneity of space and time, even where it is obvious to ordinary participants and observers.

How might capitalism look without assuming progress? It might look patchy: the concentration of wealth is possible because value produced in unplanned patches is appropriated for capital.

In this time of diminished expectations, I look for disturbance-based ecologies in which many species sometimes live together without either harmony or conquest.

the history of the human concentration of wealth through making both humans and nonhumans into resources for investment. This history has inspired investors to imbue both people and things with alienation, that is, the ability to stand alone, as if the entanglements of living did not matter.

When its singular asset can no longer be produced, a place can be abandoned.

I am not proposing a return to the Stone Age. My intent is not reactionary, nor even conservative, but simply subversive. It seems that the utopian imagination is trapped, like capitalism and industrialism and the human population, in a one-way future consisting only of growth. All I’m trying to do is figure out how to put a pig on the tracks. —Ursula K. Le Guin

By the 1930s, Oregon had become the nation’s largest producer of timber. This is a story we know. It is the story of pioneers, progress, and the transformation of “empty” spaces into industrial resource fields.

By 1989, many mills had already closed; logging companies were moving to other regions.4 The eastern Cascades, once a hub of timber wealth, were now cutover forests and former mill towns overgrown by brush. This is a story we need to know. Industrial transformation turned out to be a bubble of promise followed by lost livelihoods and damaged landscapes. And yet: such documents are not enough. If we end the story with decay, we abandon all hope—or turn our attention to other sites of promise and ruin, promise and ruin.