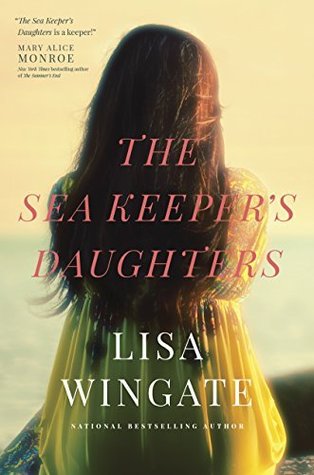

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Lisa Wingate

Read between

January 9 - January 11, 2022

Perhaps denial is the mind’s way of protecting the heart from a sucker punch it can’t handle. Or maybe it’s simpler than that. Maybe denial in the face of overwhelming evidence is a mere byproduct of stubbornness.

Could I, without seeing it ahead of time, come to a place where giving up seemed the best option? How was the thought even possible for me, knowing firsthand the pain a decision like that leaves behind? Knowing what happens in the aftermath when a person you love enters the cold waters and swims out to sea with no intention of returning to shore?

My emotions scattered like rabbits, leaving behind only two that I could identify—horror and embarrassment.

The words struck like a ricochet baseball, drilling some unsuspecting fan in the head.

If you could know—if you could always know—when the lasts in life are coming, you’d handle them differently. You’d savor. You’d stop. You’d let nothing else invade the moment.

The hard work didn’t hurt me, in truth. It taught me things. Not the least of which was that I wanted to be the boss someday . . . and when I did become the boss, I would treat people with respect, not condemnation.

I needed time to consider how best to honor her, how to treat these items with reverence, finding the right place for each one, the right person to put to good use what I couldn’t bring home.

My knowledge of my father’s family was tissue-thin and filled with holes.

Did the dead still want things? Or was death simply a letting go of all that is held so tightly in life—an understanding of the temporal and shallow nature of the human matters of possession, greed, desire, justice? I wanted to know. I so badly wanted to be certain that my mother was at peace, but it was hard to have much faith in a God who would take someone like her so young.

Clyde did make sure the dog got her exercise, though. Every morning at roughly four thirty, he prepared coffee in the world’s loudest percolator, turned CNN on at maximum volume, and threw the tennis ball down the hallway over and over and over, so the dog could chase it past my room.

I hadn’t found much of significant value. Still, I somehow couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that I’d missed an important clue—that this place held a secret I should’ve figured out by now.

Utter revulsion traveled from my head to my toes and manifested in a full-body shudder. I looked down at the floor, now a known squirrel thoroughfare. “Gross . . .” “It doesn’t happen all the time.” “Once is too often.”

Chin popping up, he looked around as if he’d awakened on a whole new planet. He was a nice kid, but I had a feeling this happened a lot. “Oh, crud . . . yeah. Dude. I gotta go.”

I fancy that, in this journey of mine, I may in some way honor the child who once danced in the fountain ’neath the moon. I have lost the carefree girl I once was, banished her to some far country and locked her away.

I’d never wondered about my grandmother’s past before, but now I wanted to understand how she had changed from Queen Ruby into a woman bitter with people and life. What had caused the reverse metamorphosis, the drawing inward, like butterfly regressing to caterpillar?

It’s not easy to change someone’s default settings, especially when they have relatives constantly dragging them down,

The trade-off for that kind of aimlessness is that, if you’re not aiming at something, you never know where you’ll end up.

Ever’body got a story, Old Dutch had told me once when I’d complained about what a shrew my grandmother was. Ever’body got a reason for what they do. You eat off somebody else’s plate, drink a their cup, could be, you’d be that same way.

Clyde’s voice shredded the peaceful afternoon air with the effectiveness of an invisible cheese grater.

Why the second thoughts? Why did I feel so unsure of this? I usually considered myself a good judge of people and an excellent judge of business. Now I felt like the insecure middle school girl again, all arms and legs and doubts.

My father’s suicide had been the result of his violent mood swings, most likely bipolar depression he was too proud to admit to—unstable brain chemistry that had gone untreated. There was nothing a little girl could have done to cause it or to stop it . . . or to deserve it.

“My pappy used to say, any day you don’t find a reason to laugh is like livin’ two days, neither one of them worth a whit.”

He tends to leave the ground first and then assess how high the jump may be.

“Here in the mountains,” she muses as the door swings open, “the people are equally afflicted with crippling poverty, but they are prepared for it. They have always lived hardscrabble, surviving on what they can grow and produce.”

A cloud shadow sweeps down the path and then dances up a ridge, disappearing into a smoky mist that comes out of nowhere. I am struck by the contrasts of this place, the suddenness of light and shadow, of storm and clear sky, of threat and welcome.

To understand life, one must experience it!” Her silver-flecked eyes seem to bore through me as if she is well aware that I have been keeping Emmaline away from these mountain people and their children, who are oft clothed more in scabs and vermin than in pants or shorts or dresses.

it dawns on me now that we never asked any of them for their stories. In all those years, it never occurred to me to care.

The words paint pictures and I live Mr. Bass Carter’s life through lines and pen. This, I know now, is story at its highest capability. It agitates us to genuine joy and tears. Within story, we are given a new soul, another’s soul to try on like clothing, knowing we can shed it again should we choose.

Our route from there takes us along winding and shadowed corridors that slither through narrow valleys and climb mountainsides like poorly stitched ribbon on a girl’s dress, ruffled and shrunken, torn and folded.

Life is a process of storms and rebuilding,

We, in our humanness, cannot help but foolishly desire eternity in this life.

Sometimes your heart just takes a turn and the next thing you know, you’re headed in a whole new direction.”

I understood it then—the exact position he was in. It was always hard to gauge the timing when someone new came into my life. How long do you wait before you say, My father committed suicide when I was five? How long do you maintain an acquaintance before you show your scars? What do you do with the surprise and sympathy that come afterward?

So many of the world’s ills could be cured if only we knew the joys and hardship of others’ paths.

A well-read mind does not cease its hunger because physical circumstances change. Mr. Ross has devoted his time here to documenting the native plants and how they are used medicinally and as foodstuffs.

Just like your mama. Was I anything like her? My mother was the best person I’d ever known. She had a nose for potential. She found it in pieces of sea glass and driftwood, and in people. She always wanted those around her to see the greatest possible versions of themselves. That passion made her a fantastic teacher.

Sometimes self-delusion is the only thread left to keep you hanging upright. But delusions are slippery things to hold on to.

But every once in a while—and y’all young folks can mark my words on this, because it’s somethin’ that’ll be true as life goes on—every once in a while, you hit a minute in your life when you know the Almighty is standin’ right over your shoulder, and he’s expectin’ you to be true to yourself—to the moral fiber you got inside. And if you don’t stand up for that, you’re gonna be less of yourself tomorrow than you was today. You gotta make your decision in the blink of an eye. Who you gonna be?

The idea was like a handful of Mexican jumping beans. Explanations and emotions bounced everywhere at random, but the clearest one I could grab was, Whitney, if you walk out of his life without seeing if this is for real, you really are an idiot.

The heart is a wellspring. It has infinite capacity to manufacture love. The only barriers are the ones we put in the way.

As always, the Outer Banks had a magic all its own.

Conflicting urges warred—two instinctive reactions. I needed to rely on someone, but relying on people was dangerous. At any moment, people could decide to just . . . not be there anymore. I’d always relied on myself.

By closing herself away, my grandmother had gained nothing. She’d withered within her own walls long before her death. She’d worn misery like a cloak and covered those closest to her in its suffocating fabric.