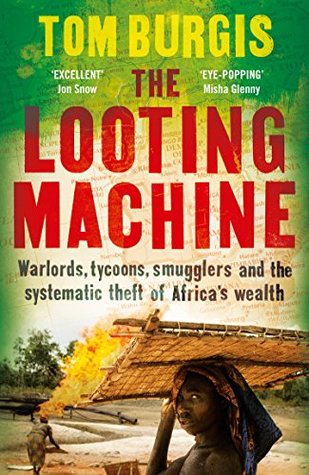

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tom Burgis

Read between

August 1 - August 13, 2020

There are plenty of theories as to the causes of the continent’s penury and strife, many of which treat the 900 million people and forty-eight countries of black Africa, the region south of the Sahara desert, as a homogenous lump.3

Africa’s troves of natural resources were not going to be its salvation; instead, they were its curse.

Analysts at the consultancy McKinsey have calculated that 69 per cent of people in extreme poverty live in countries where oil, gas and minerals play a dominant role in the economy and that average incomes in those countries are overwhelmingly below the global average.5

At extreme levels the contract between rulers and the ruled breaks down because the ruling class does not need to tax the people to fund the government – so it has no need of their consent.

The resource industry is hardwired for corruption. Kleptocracy, or government by theft, thrives. Once in power, there is little incentive to depart. An economy based on a central pot of resource revenue is a recipe for ‘big man’ politics.

Africa accounts for 13 per cent of the world’s population and just 2 per cent of its cumulative gross domestic product, but it is the repository of 15 per cent of the planet’s crude oil reserves, 40 per cent of its gold and 80 per cent of its platinum – and that is probably an underestimate, given that the continent has been less thoroughly prospected than others.

In 2010 fuel and mineral exports from Africa were worth $333 billion, more than seven times the value of the aid that went in the opposite direction (and that is before you factor in the vast sums spirited out of the continent through corruption and tax fiddles).

Many of the hundreds of resource executives, geologists and financiers I have met believe they are indeed serving a noble cause – and plenty of them can make a justifiable case that, without their efforts, things would be much worse. The same goes for those African politicians and civil servants striving to harness natural resources to lift their compatriots from destitution.

MPLA bigwigs and the family of José Eduardo dos Santos, the party’s Soviet-trained leader who assumed the presidency in 1979, took personal ownership of Angola’s riches. Isabel dos Santos, the president’s daughter, amassed interests from banking to television in Angola and Portugal. In January 2013 Forbes magazine named her Africa’s first female billionaire.

In 1999, as the war entered its endgame, dos Santos appointed him to run Sonangol, the Angolan state oil company that serves, in the words of Paula Cristina Roque, an Angola expert, as the ‘chief economic motor’ of a ‘shadow government controlled and manipulated by the presidency’.

In 2011 Sonangol’s $34 billion in revenues rivalled those of Amazon and Coca-Cola.

Oil accounts for 98 per cent of Angola’s exports and about three-quarters of the government’s income.

When the International Monetary Fund examined Angola’s national accounts in 2011, it found that between 2007 and 2010 $32 billion had gone missing, a sum greater than the gross domestic product of each of forty-three African countries and equivalent to one...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Oil and mining companies have been the subject of more cases under the FCPA and similar laws passed elsewhere than any other sector.

Depending on the vagaries of supply chains, if you have a PlayStation or a pacemaker, an iPod, a laptop or a mobile phone, there is roughly a one-in-five chance that a tiny piece of eastern Congo is pulsing within it.