More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 25 - December 20, 2017

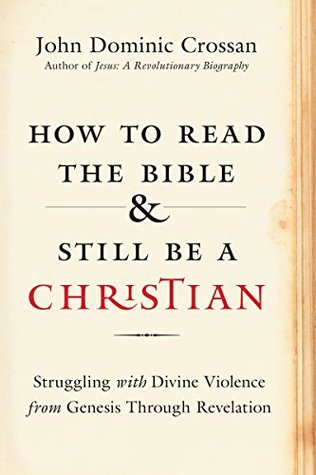

An Old Testament bad-cop God and a New Testament good-cop God were persuasive only to those who had never actually read the entire Christian Bible.

will go a step farther and argue that distributive justice is the primary meaning of the word “justice” and that retributive justice is secondary and derivative.

The heart of God’s justice is to make sure that the “weak and the orphan” have received their share of God’s resources for them to live and thrive. Retributive justice comes in only when that ideal is violated.

the disjunction between God as violent and nonviolent can be rephrased for the rest of this book like this: the biblical God is, on one hand, a God of nonviolent distributive justice and, on the other hand, a God of violent retributive justice.

A vision of the radicality of God is put forth, and then later, we see that vision domesticated and integrated into the normalcy of civilization so that the established order of life is maintained. Furthermore, both elements are cited from, in one case, the mouth of God and, in the other, the pen of Paul.

Jesus the Christ of the Sermon on the Mount preferred loving enemies and praying for persecutors while Jesus the Christ of the book of Revelation preferred killing enemies and slaughtering persecutors. It is not that Jesus the Christ changed his mind, but that in standard biblical assertion-and-subversion strategy, Christianity changed its Jesus.

it contains both the assertion of God’s radical dream for our world and our world’s very successful attempt to replace the divine dream with a human nightmare.

The norm and criterion of the Christian Bible is the biblical Christ. Christ is the standard by which we measure everything else in the Bible. Since Christianity claims Christ as the image and revelation of God, then God is violent if Christ is violent, and God is nonviolent if Christ is nonviolent.

We are called Christ-ians not Bible-ians,

If, for Christians, the biblical Christ is the criterion of the biblical God, then, for Christians, the historical Jesus is the criterion of the biblical Christ. This

the sense of its nonviolent center judges the (non)sense of its violent ending.

with all due respect to Islamic tradition, we are not “the People of the Book.” We are “the People with the Book,” but even more importantly, we are “the People of the

Christianity’s godsend is not a book but a person, and that person is the historical Jesus. It is precisely that historical Jesus whom Christians proclaim as “the glory of Christ, who is the image of God” (2 Cor. 4:4). Succinctly put, for Christians, Incarnation trumps Apocalypse.

In any case, that garden in Eden is imagined as a super-garden well-watered by a super-river and presumably located in northern Mesopotamia. (That location for the garden may also explain why “the mountains of Ararat” were chosen for the ark’s landfall in Gen. 8:4. Re-creation in Gen. 8–9 started again where it began in Gen. 2–3.)

Israel knew, as did the entire Fertile Crescent, that the Epic of Gilgamesh and Enkidu was not a tragic tale of “if only” Gilgamesh had not taken that cool swim, he would have been immortal. They also knew that Genesis 2–3 was not a tragic tale of “if only” Adam had not taken that first bite, humanity would have been immortal. Both these stories were metaphorical warnings against transcendental delusions of human immortality. They were parables proclaiming that death is our common human destiny.

Israel could create the majesty of Torah, the glory of prophecy, the beauty of psalmody, and the challenge of wisdom without affirming an eternal afterlife for itself. Israel may have left Egypt, but it never left Mesopotamia.

In other words, the normalcy of human civilization is not the inevitability of human nature.

We humans are not natural-born killers (if we were, would we suffer posttraumatic stress after battle?). The mark of Cain is on human civilization, not on human nature. Escalatory violence is our nemesis, not our nature;

We humans are not getting more evil or sinful but are simply getting more competent and efficient at whatever we want to do—including sin as willed violence.

Think, finally and especially, about two details in this treaty’s Law. One is that love means loyalty:

Another is that loyalty means exclusivity:

those Assyrian-style suzerain-vassal treaties—with their heavy emphasis on Sanction rather than History and, within Sanction, on curses for infidelity rather than blessings for fidelity—are the contemporary metaphor, model, and matrix for the Deuteronomic vision of covenant. Indeed, it is even possible to show direct contacts between Assyrian and Deuteronomic covenantal curses.

In summary, therefore, I argue that the Deuteronomic tradition’s vision of Israel’s covenant with God was modeled on contemporary Assyrian-style treaties and thereby greatly enlarged the role of Sanction within covenant and curses and punishments within Sanction.

Classic discrepancies such as Manasseh and Josiah required historical “correction” by the Chronicler to bring history into line with theology. Furthermore, the same happens even more strikingly outside the Deuteronomic tradition. The Case of Job:

had happened and therefore Job had sinned. We—hearers or readers—know from the very start of the book that such a Deuteronomic interpretation of Job’s situation is false, and indeed, God negates it at the start (1:8) and finish (42:7) of the book.

contrast again the Priestly tradition in Genesis 1 with the Deuteronomic tradition in Deuteronomy 28, I glimpse again that biblical rhythm of expansion-and-contraction, assertion-and-subversion.

recognize radicality’s assertion, expect normalcy’s subversion, and respect the honesty of a story that tells the truth.

It makes a profound difference whether from that central core of covenantal Law in the present, one moves mostly to past History in gratitude to God or mostly to future Sanction in fear of God.

What is ultimately at stake across that Covenantal Divide is the character of the biblical God as one of distributive justice or of retributive justice, as graciously nonviolent or punitively violent.

In other words, justice is not simply personal and individual, but more especially systemic and structural—especially for a society’s vulnerable ones.

far too much of Assyrian imperial theology entered Israelite covenantal theology; far too much of the God Ashur entered into the God Yahweh in the biblical tradition.

both the Prophetic and Psalmic traditions are extremely ambiguous on the character of God. Indeed, there is almost a rhythm of assertion-and-subversion within and across each tradition.

Israel against Rome was never simply the standard conflict of the conquered against the conqueror, a colony against an empire. Instead, it was a clash between eschatological visions as Israel proclaimed a still-future Golden Age and Rome an already-present Golden Age. A just, peaceful, and nonviolent world was the still-future eschaton for Israel but the already-present empire for Rome.

Desmond Tutu, preaching at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, California, in 1999: “God, without us, will not; as we, without God, cannot.”

For Jesus, therefore, nonviolent resistance to evil is divine before it is human and should be human because it is divine.

It is a fascinating summary of Roman imperial theology, but as you read it, replace “Caesar” or “Augustus” with “Jesus” or “Christ,” and you can understand Pauline Christian theology as counterpoint to and confrontation with Roman imperial theology.

set the stage to correct erroneous accusations that Paul betrayed Jesus and Judaism, invented Christianity, used weird new terms, made weird new claims, was anti-Semitic and antimarriage, proslavery and propatriarchy. Much or all of those issues stem from ignorance of the terms and claims of Roman imperial theology and of how Paul proclaimed Jesus’s vision of God’s Kingdom both as a challenge to his fellow Jews and as a confrontation between Christ and Caesar. For that two-front struggle, his language was deliberately designed to be appropriate to the provincial capitals of the Roman Empire.

beneath that seismic conflict of Christian Judaism and Roman imperialism was the grinding collision of history’s two great tectonic plates: the normalcy of civilization’s program of peace through victory against the radicality of God’s program of peace through justice.

In other words, Paul was saying that just as Christ was executed and was thereby dead by Rome, so Christians were baptized and thereby dead to Rome. They were dead, specifically, to Rome’s four supreme values of patriarchy, slavery, hierarchy, and victory—especially violent victory on which those other three values depended.

Paul calls Onesimus by his name and never refers to him as “your slave.”

It is clear, then, that the baptismal commitment of “no longer slave or free” is neither hyperbole nor hypocrisy but program and platform. It means that Christians cannot own Christians.

What Jesus forbids is violent resistance against evil.

“I Permit No Woman to Teach or to Have Authority over a Man” AS FOR SLAVERY, SO for patriarchy: real-Paul is flatly contradicted by post-Paul.

First, the entire section is found at different locations among the earliest extant manuscripts of the letter. Some have it here, and others have it after 14:40—that is, at the end of the chapter. The best explanation for this discrepancy is that it was not originally part of the letter; that a copyist wrote it in the margin as his own version of 1 Timothy 14:33b–36, and later copyists inserted it from the margin into the text at two different places.

PAUL WAS NEVER TERRIBLY hard to understand on the theoretical and theological levels. Instead, he was terribly hard to follow on the social and practical levels. The same goes for Jesus before him: easy to understand, difficult to follow.

When you actually read the entire text from start to finish, you notice that those just-seen bipolar characteristics of God are more successive than simultaneous, and more alternating than parallel.

reject absolutely any response claiming that the Old Testament depicts a God of justice as vengeance and the New Testament one of love as mercy. As you know by now, that works well as long as you do not make the mistake of actually reading the Christian Bible all the way to its climactic violence in the book of Revelation.