Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 9 - December 22, 2020

ceramic complexes in the LMV do not belong to a single ceramic complex but rather represent a concentration of art forms which do not observe boundaries. The concentration of art forms in the LMV “appears to be a center of a distribution pattern that ranges far beyond the valley itself”

“Southwestern contacts in the Southeast happened several times over the course of several centuries, which argues for some long-term functioning of a trade network from the Southwest at least as far as the Mississippi Valley”

From AD 400 to 700, prior to the emergence of Mississippian culture, LMV potters made large grog-tempered or sand-tempered jars with round bases for domestic purposes.

Substantial social, political, and technological changes took place in the LMV around AD 800 to 850, with the emergence of Mississippian culture in northeast Arkansas and southeast Missouri

Rituals associated with corn agriculture and new social arrangements also may have been introduced, which required specific ceramic assemblages that emphasized a transformed cosmological order.

Shell-tempered pottery became widespread by AD 800, originating in the LMV. By AD 800–900 major changes in pottery technology took place in connection with other technological and social changes of the ninth and tenth centuries

Stronger and lighter vessels could be constructed with the new tempering agent and ceramic vessels could easily be modified into a ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The proximity of Cahokia may have been a significant and widespread influence on LMV populations.

“Mutual trade and knowledge between these two districts or regions manifest themselves in the ideas, artifacts, and raw material shared by both.”

“bow and arrow, house type, discoidal, hooded bottle shape, bone harpoon, microlithic industry, pottery disc, and elbow pipe form” in addition to the use of imported cherts (including hoes and other bifaces) and the exchange of conch ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

There are artifact similarities to Cahokia in the Central Valley, but to date only a few artifacts possibly manufactured at Cahokia have been recovered. Yet contact with, knowledge of, and trade with the Central Valley was certainly involved. In addition, there probably was a basic linguistic relationship.

By approximately AD 1000 small clusters of Mississippian settlements were spread throughout the Mississippi Valley from about modern-day Memphis to St. Louis. A great deal of ceramic innovation occurred in a relatively short time, based on changes in pottery assemblages.

flat bases, beakers, and beaker-shaped bowls with rim effigies. The new suite of ceramic fineware may represent a reorientation in ritual that emphasizes mortuary ceremonialism.

“Death is apparently this society’s major excuse for ceremonial gathering.”

In addition to ceramic vessels, painted conch shells, used as cups, have been reported.

Sherds representing vessels exchanged from distant areas have been found in twelfth-century contexts, underscoring the matrix of exchange networks.

“The presence of a SECC item in a discrete nonhabitation mortuary area is indicative of increasing complexity with the local community, and participation in the regional ideological system.”

The beaker appears to have functioned as a ceremonial drinking vessel

and the ceramic assemblage in general appears to have been used for mortuary libation ceremonies

Burial associations further indicate that beakers were special vessels used for rituals in which libation was critical.

The burials are normally sets of bundled, disarticulated bones rather than articulated skeletons, suggesting that they were curated until the proper time for burial had arrived. Such rites of intensification “are calendrically based, community-focused rites that play a critical role in the resolution of cosmological discontinuities in the annual ritual sequence”

Perhaps the libation was cooked in jars, poured into bottles, and in turn poured into the bowls or beakers from which it was consumed, a pattern of ritual medicine preparation and consumpt...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

bottles may have been used in the preparation of ritual medicines and served to transform the cooked “medicines” into a sacred drink; thus the motifs which embellished the bottle...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Many of these eleventh- and twelfth-century sites were burial mound clusters with little if any resident population. The vacant ritual center often included mounds in varying states of use, including a council house, a bun...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The settlement pattern was a set of dispersed farmsteads and small villages ritually connected to...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Ceremonial centers postdating AD 1150 reveal evidence of residential debris, suggesting that dispersed populations were beginning to move into the mound precincts and transforming them into central places which then had to be protected through fortification. These fortif...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Evidence from slightly later suggests that a major object in warfare was the appropriation or destruction of one’s enemies sacra and connections with the Other World

Morse and Morse (1990:158) have termed the AD 1200–1400 period the Matthews Horizon and note that it was a time of great change.

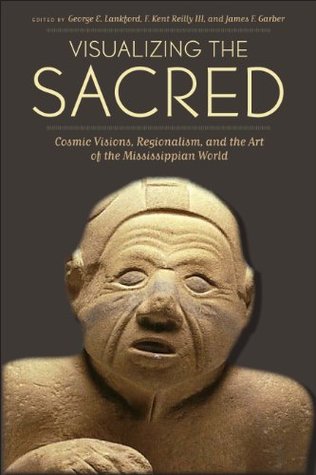

Centering and alternating of motifs represents an ancient principle in the Southeast, especially in the Coles Creek Culture to the south and southwest of the LMV. Thirteenth- and fourteenth-century motifs include interlocking scrolls, ogees, sunbursts, cross-in-circles, nested triangles and circles, and alternating terraces that are often painted, incised, or engraved. Figural art emphasizes the Great Serpent (Fig. 5.3), while modeled vessels generally depict females seated in highly stylized positions. The female effigies appear to represent residents of

the Beneath World, such as Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies (Fig. 5.4).

Although effigies have been an important component of the ritual ceramic repertoire, many more forms are added to the inventory beginning in the fourteenth century. They embrace a wide variety of forms, including alligator, anhinga, animal, basket, bat, bear, beaver, bird, buffalo horn, canoe, cat monster, corn, corn god, crawfish, deer, dog, duck, fish, frog, goose, gourd or squash, hawk, human, mace, opossum, otter, owl, rabbit, serpent, shell, shell univalve, turkey, turtle, underwater monster, unidentified animal, unknown, whelk shell, and zoomorph

In the mid-sixteenth century

Large jars at this time occasionally serve as burial urns, a widespread characteristic of late sixteenth-century cultures, especially in south-central Alabama.

By the mid-seventeenth century a decline takes place in the types of ritual vessels

engraving represents the last element of the rich ritual ceramic sets in the LMV.

Between approximately 1560 and 1580 a major drought took place (Stahle, Cleveland, and Hehr 1985; Stahle et al. 2000), which “essentially destroyed the existing regional ecosystem”

When French explorers visited the LMV in the late seventeenth century, the valley was virtually depopulated.

Polities in circumscribed river valleys, such as the Etowah and Black Warrior River Valleys, enabled consolidation of neighboring groups and the appropriation of social labor and surplus food as tribute.

In the lower portion of the Northern Mississippi Valley, on the other hand, incorporation of adjoining local groups would have been more difficult, as neighbors had a greater number of allies with which to ally themselves in order to fend off aggressive polities. With the resulting lack of political complexity, highly skilled crafting in workshops would have been limited.

The resulting implication is that utilitarian ritual ware would become the foundation for endless ritual

feasting among political groups engaged in endless internecine rivalries and factional competition.

In the Late Mississippian period (AD 1400–1541) certain specialized pottery vessels produced in the Lower Mississippi Valley (LMV) were either sculpted or incised with an interesting array of zoomorphic figures. Such zoomorphic imagery is entirely lacking in the abstract designs on Ramey Incised pottery produced at Cahokia during an earlier period. Prominent among these zoomorphic images is a series of winged serpents, although the serpent imagery is not limited to winged creatures.

related in some way to the winged serpent imagery found on the somewhat earlier (AD 1300–1450) Moundville Engraved, var. Hemphill pottery

certainly, even an initial examination offers evidence that these engraved vessels from Moundville are at least stylistically related...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the winged serpents from both Moundville and the LMV represent the same Great Serpent that seems ubiquitous in the Native American ideological systems of eastern North America

while the Moundville winged serpents inhabit the sky realm exclusively—the LMV winged serpents can be identified by their respective specific secondary symbols as inhabiting the watery Beneath World just as often as they travel in the celestial realm of the Above World.

Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands viewed themselves as inhabiting a multileveled cosmos.

the most common view was that the cosmos consisted of at least three levels: the Above World, the Beneath World, and the Earthly Plane

the location of the Great Serpent within the night sky corresponds to the constellation Scorpio

Functioning within this nocturnal celestial location, the Great Serpent serves as guardian of the “Path of Souls” or Milky Way