Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 9 - December 22, 2020

An extensive precedent exists for considering the Mississippian cultures of the Mississippi Valley (particularly near the junction with the Ohio) to be the ancestors of the Siouans—particularly the Dhegiha and Chiwere (including the Ho-Chunk) branches of the Siouan linguistic family

It is not difficult to connect the Dhegiha Sioux to the archaeology of the Prairie Peninsula and to the great townsite of Cahokia.

Dhegiha Sioux have long been recognized as standing apart from other tribal organizations in the roles that their cosmology plays: in rites relating to success in war (framed in terms of defense of tribe members from external threats) and in their emphasis on promoting life-supporting processes—above all in the preservation of the tribe

To these we can add the strong preference for personifying spiritual forces, whether animate or inanimate.

The three parts of the universe are graphically delineated. The empyrean Upper World was occupied by important stars, the sun, and the moon. The Pleiades, the Big Dipper, the Milky Way, and the Morning Star were among the stars. In the lowest register of this Upper World were war clubs flanking a rainbow.

four world levels that humankind descended to reach the earth. Beneath the lowest level was the red oak tree they landed upon when they fell into “This World.”

Centered beneath the tree trunk was a shaft that was left unexplained by the draftsperson. It undoubtedly represented the passage to the “Beneath World,” usu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the inhabited middle world was likened to an island surrounded b...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

is important to learn how the camp circle embodied Dhegiha cosmovision centering around the earth-sky moiety social division.

In this light the tribe looks more like a coalition of clans, whose mutual interdependence was structured by important rites parceled out among its participants. Each clan (and subclan) exercised exclusive control over its rites and bundles. The only rites not controlled by individual clans were under the control of sodalities (such as the Shell Society) and were part of the He’dewachi ceremony. Unity was created by interweaving complementary rights and interests. The order of the clan within the circle became a cosmologically ordained way of maintaining

collective cohesion in the face of countervailing fissiparous tendencies.

The recognition of Dhegiha Sioux myths and religious symbolism in specific images is already well advanced. Rock-art has provided images of the Dhegiha Birdman and Earthmother

Duane Esarey (1987, 1990) argued that engravings on shell gorgets of the Braden/Eddyville style or the McAdams type that bear spiders fit the beliefs and practices of the Osage far better than those of the distant Cherokee.

In a pathbreaking paper Guy Prentice (1986) contended that the Birger Figurine represented “Mother Corn” or “Our Grandmother.” Diaz-Granados (1993:341, 343–345, 354; Diaz-Granados and Duncan 2000:217, 219–220, 236–237) argued for the “Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies” as a Siouan deity. This particular divinity—called Earthmother here—can be identified among a broad range of tribes in the Northern Plains and Eastern Woodlands, including the Dhegiha Sioux.

Of particular significance for these identifications is the graphic concordance between the details incorporated into these figurines and the story lines in the oral traditions of the Eastern Plains.

We have to recognize that the red fireclay figurines associated with Cahokia depict numerous different deities.

The connections to Dhegihan cosmology are facilitated by the emphasis on representation of spirits through human form. The transformation to and from an animal or cultural object and a human form is recounted many times in Dhegiha and Chiwere mythology.

What appear to be set scenes representing episodes from a myth can be found in some sculpture, rock-art, and shell engraving (Brown 2007b). Reilly (2004) has identified at least three myth cycles among the many combinations in human costumery. Two of the three mythic cycles identified, the Morning Star Cycle and the Earth and Fertility Cycle, are depicted prominently in the Braden style; the third cycle, the Path of the Souls, is present, albeit weakly

The Morning Star Cycle is built around the predawn appearance of a bright asterism in advance of the rising sun.

Fertility in general is not what the Morning Star cycle is all about; rather it applies specifically to human life in its multiple aspects, including health, safety, and the protection of one’s family.

it places death as a preordained end that normally contains the germ for a new birth.

The hawk is the principal animal form of Morning Star. Other icons are the forked eye surround, the Long-Nosed God maskette, the chunkey stone, the chunkey pole, and the calumet staff. The images created in Classic Braden style clearly reference a hawk.

A related symbol of human fertility is the Long-Nosed God depicted as maskettes in the ears of Birdman/Morning Star

An important life symbol present is the bilobed arrow emblem.

The feature that signifies continuity is the “arrow” in name and imagery.

Long-competing symbols of vegetative fertility are the puma and the serpent. The human counterpart of these two animals, and perhaps their controlling deity, is Corn Mother or Earthmother

Their opposite was Morning Star, as represented by the Sacred Hawk

11). The vulvar motif has been shown to be a recurrent symbolic representation of this female deity

Another associated object is the lidded chest that probably depicts a deep fl...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“Old-Woman-Who-Ne...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Corn Mother or Ear...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

One can posit two aspects to Old Woman: as the bearer of a backpack containing agricultural seeds and as the guardian of a major sacred bundle represented by a large lidded box she protects either by sitting next to it or by laying her hands on it.

While the Morning Star spirit constitutes a certain vision of battle tied to human regeneration, Turtleman embodies outright prowess

Turtle is a warrior figure embodied in red stone statuary

The figures sculpted in stone depict the defeat of a captive (Fig. 3.4c). They bear their turtle identity in the warrior’s distinct carapacelike body armor ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Yet to be placed into a particular cycle is the power that I have called “Grizzlyman”

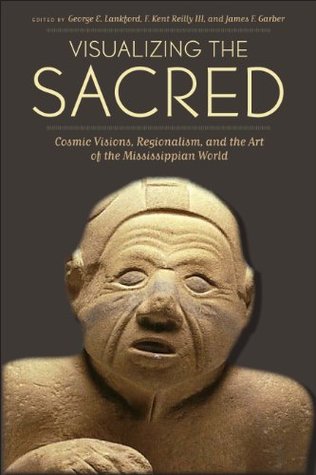

The sole exemplar of this deity is a figurine of red claystone from Spiro converted into a pipe

This figurine combines features of dwarfism (the hunched back and enlarged head with prominent bossing on the sides of the forehead) with an open, gap-toothed, snarling mouth and a pair of hair-knots that Richard Zurel (2002) has shown to be signature markers of the grizzly bear in frontal view.

the deer head is clasped in its left hand. This kenning for “deer head” or tapa’ is

the name for the constellati...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The combination of body features and deer head suggests some sort of arch-shaman. Reilly (2004:133, Fig. 18), however, has identified this “Grizzly Man” with the leader of the Giants. How Grizzlyman and the Giants are related remains to be studied.

The spider and its web are an icon for life as a primordial principle. Both are sometimes associated with Earthmother

Osage believe the spiderweb is a snare, ho e ka (Fig. 3.7). According to La Flesche (1932:63), it is “a term for an enclosure in which all life takes on bodily form, never to depart therefrom except by death. It stands for the earth which the mythical elk made to be habitable by separating it from the water.” In other words, it “refers to the ancient conception of life as proceeding from the combined influences of the cosmic forces.”

The serpent and the puma stand as different forms of the life-taking spirit/deity (Brown 1997). Lankford (2007d) has argued that universally the “Great Serpent” is made to represent the Beneath World. When it is displayed as winged, he contends, the reference is not to the serpent’s appearance but to the snake flying in the night sky

Lankford (2007a) has elaborated on the winged serpent and Piasa as such a night sky deity. The winged serpent is emblematic of Lankford’s (2007a, 2007b) cult of the Path of the Souls.

As a life-taking monster this spirit was widely feared. This cycle is presumably connected with the motifs of skulls and long bones. It is contemporary with the appearance of the winged Piasa, the terrace rainbow motif, and the circular scalp lock (Brown 2007a).

On the cultural side there is the fact that spirits/deities have what could be considered overlapping domains. For instance, life, birth, and fertility are shared in certain ways among the spider, Birdman, Earthmother, and even the serpent.

On the symbol side complexity is manifest in the blurred distinctions in images that appear to have very different histories or origins. An outstanding case is the seemingly vague distinction between the Sacred Hawk and the Thunderbird. Whereas the Sacred Hawk is derivative of the twelfth-century falcon, the Thunderbird of postcontact times is associated with the powers of thunder and lightning.

Cosmovision is such a strong manifestation of cultural ideology that arguably it is highly resistant to changes induced by European colonization. Consequently, associated imagery is presumed to be likely to carry across that event and well into the present

The regional framework adopted here follows the now-recognized patterning of Mississippian-period art styles. By assuming that these styles are material manifestations of specific languages, meanings can be inferred for particular iconographic contexts and, by projection, the devices of specific languages.