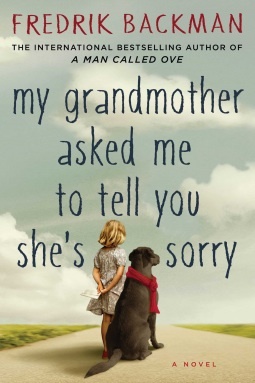

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 10 - April 14, 2025

“Changing memories is a good superpower, I suppose.” Granny shrugs. “If you can’t get rid of the bad, you have to top it up with more goody stuff.” “That’s not a word.” “I know.” “Thanks, Granny,” says Elsa and leans her head against her arm.

But Miamas is Granny and Elsa’s favorite kingdom, because there storytelling is considered the noblest profession of all. The currency there is imagination; instead of buying something with coins, you buy it with a good story.

Granny doesn’t like it when people say that things are made-up, and reminds Mum she prefers the less derogatory term “reality-challenged.”

Elsa’s mum is the boss. “Not just a job, but a lifestyle,” Granny often snorts. Mum is not someone you go with, she’s someone you follow. Whereas Elsa’s granny is more the type you’re dodging rather than following, and she never found a scarf in her life.

“Touché,” Granny mumbles and inhales deeply. (That’s one of those words Elsa understands without even having to know what it means.)

But Granny grabs her fingers and squeezes them in her hands like she always does, and it’s difficult to be afraid when someone does that.

Elsa is the sort of child who learned early in life that it’s easier to make your way if you get to choose your own soundtrack.

It’s very difficult not to love someone who can hear you say something as horrible as that and still be on your side.

Lennart sits next to her, waiting for the coffee. Meanwhile he sips from a thermos he has brought with him. It’s important to Lennart to have standby coffee available while he’s waiting for the new coffee.

Granny nods as a courtesy and tells the whole story anyway. Because no one ever taught Granny how not to tell a story. And Elsa listens, because no one ever taught her how not to.

Having a grandmother is like having an army. This is a grandchild’s ultimate privilege: knowing that someone is on your side, always, whatever the details. Even when you are wrong. Especially then, in fact.

Granny says people who think slowly always accuse quick thinkers of concentration problems. “Idiots can’t understand that non-idiots are done with a thought and already moving on to the next before they themselves have. That’s why idiots are always so scared and aggressive. Because nothing scares idiots more than a smart girl.”

Maud pats her on the cheek and looks so upset on Elsa’s behalf that Elsa gets upset on Maud’s behalf.

Because not all monsters were monsters in the beginning. Some are monsters born of sorrow.

Improbable catastrophes produce improbable things in people, improbable sorrow and improbable heroism.

Mum sighs deeply as only a parent who has just realized that she has strayed considerably further into a story than she was intending is capable of sighing.

Dad is spectacularly bad at dancing; he looks like a very large bear that has just got up and realizes its foot has gone to sleep.

You can’t kill a nightmare, but you can scare it. And there’s nothing so feared by nightmares as milk and cookies.

But she doesn’t want to disappoint him, so she stays quiet. Because you hardly ever disappoint anybody if you just stay quiet. All almost-eight-year-olds know that.

The mightiest power of death is not that it can make people die, but that it can make the people left behind want to stop living,

Fears are like cigarettes, said Granny: the hard thing isn’t stopping, it’s not starting.

the knights did the only thing you can do with fears: they laughed at them. Loud, defiant laughter. And then all the fears were turned to stone, one by one.

Maud has brought cookies and Lennart decides when he gets to the house’s entrance to bring the coffee percolator, because he’s worried they may not have one at the hospital. And even if they do, Lennart has the feeling it will probably be one of those modern coffeemakers with a lot of buttons. Lennart’s percolator only has one button. Lennart is very fond of that button.

Granny then said the real trick of life was that almost no one is entirely a shit and almost no one is entirely not a shit. The hard part of life is keeping as much on the not-a-shit side as one can.

“ ‘We want to be loved,’ ” quotes Britt-Marie. “ ‘Failing that, admired; failing that, feared; failing that, hated and despised. At all costs we want to stir up some sort of feeling in others. The soul abhors a vacuum. At all costs it longs for contact.’ ”

She is still crying. Wolfheart as well. But they do what they can. They construct words of forgiveness from the ruins of fighting words.

The problem is this whole issue of heroes at the ends of fairy tales, and how they are supposed to “live happily to the end of their days.” This gets tricky, from a narrative perspective, because the people who reach the end of their days must leave others who have to live out their days without them. It is very, very difficult to be the one who has to stay behind and live without them.

And they never talk much about it afterwards. Because certain kinds of friends can be friends without talking much.

“How am I like him, then?” “You have his laugh.” Elsa retracts her hands into her sweater. And slowly swings the empty sleeves in front of her. “Did he laugh a lot?” “Always. Always, always, always. That was why he loved your grandmother. Because she got him to laugh with every bit of his body. Every bit of his soul.”

Mum laughs so loudly and for so long about it that Elsa starts getting seriously worried about the hummingbird. “You’re the sharpest person I know, do you know that?” And she thinks, Well, that’s nice and all that, but Mum really needs to get out there and meet a few more people.

Marcel belly-laughs. You’d have to call it that. A belly-laugh. It’s far too noisy to be a laugh. Elsa likes it a great deal. It’s quite impossible not to.

Marcel puts his hands together. Nods with sadness, also happiness. Like when one has eaten a very large ice cream and realizes it is now gone.

They laugh until no one can forget that this is what we leave behind when we go: the laughs.

But he looks much calmer when Elsa tells him he can make the invitation cards. Because Dad immediately starts thinking about suitable fonts, and fonts have a very calming effect on Dad.

But in Miamas a newborn doesn’t get a godparent, newborns get a Laugher instead. After the child’s parents and granny and a few other people that Elsa’s granny, when she was telling Elsa the story, didn’t seem to think were terribly important, the Laugher is the most important person in a child’s life in Miamas. And the Laugher is not chosen by the parents, because Laughers are far too important to be chosen by parents. It’s the child who does the choosing. So when a child is born in Miamas, all the family’s friends come to the cot and tell stories and pull faces and dance and sing and make

...more