Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 5 - August 26, 2016

Both men believe in a system by which the manipulation of symbols creates material change in the real world. Both explicitly use their creative work in multiple media as an attempt to cause such change. Their comics are magic spells hurled into the culture wars, trying in their own way to reshape reality.

For Ballard, at least, the goal of science fiction was to abandon outer space in favor of “inner space," which he defined in 1968, saying it’s “an imaginary realm in which on the one hand the outer world of reality, and on the other the inner world of the mind meet and merge. Now,” he continued, “in the landscapes of the surrealist painters, for example, one sees the regions of Inner Space; and increasingly I believe that we will encounter in film and literature scenes which are neither solely realistic nor fantastic. In a sense, it will be a movement in the interzone between both spheres.”

the cut-up technique, in which written works are physically shredded into strips and remixed to produce new phrases, a practice Burroughs believed to have actual magical import, to the extent that he joined the chaos magic organization the Illuminates of Thanateros late in life.

The visionary nature of William Blake defies the usual genre divisions and, perhaps more problematically, subject divisions. It is simply not accurate to treat him as a poet or as an artist, nor even as a comics creator, although comics scholars have produced some of the most compelling work on Blake of of recent years.

The annihilation of selfhood should be taken not merely as a mystical experience but as work

This reality makes the work of a visionary comics producer harder. The need to take on commissions and side work means that Talbot, instead of creating his works of pioneering vision like he has spent much of his career on Judge Dredd and Batman stories or illustrating cards for Wizards of the Coast’s Magic: The Gathering money factory.

Yes, Superman is an alien, but the situation is visibly just the reverse of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter, who has vast physical abilities when transported to Mars because his body is better adapted to the planet. Jerry Siegel even admits to the inspiration, and his powers were far less impressive in the early days than they are now.

Whatever the idea of the superhero is, it resists a straightforward definition that links it inextricably to Superman. It is, however, telling that superheroes are inexorably associated with one particular medium: comic books. This separates them from almost any other popular genre, and suggests a more useful way of isolating them from adjacent genres.

What Action Comics #1 indisputably was is the first massively successful attempt at the pulp hero to be defined by colorful visual representation. Technologically speaking, this was not popular until cheap four-colour printing was possible.

The cleverness of Superman was that he used color well. He was bright - even lurid, and Siegel and Shuster had what was, for the time, a shockingly kinetic style of visual storytelling. What was crucial was not the idea of a costumed hero with special powers, but the fact that this particular costumed hero was interesting because he looked good.

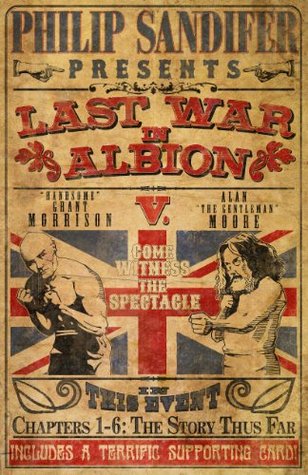

It is telling that the War begins over the subject of repetitive stories that blend genre tropes willy-nilly and are comprised of action set-pieces.

Their text was a sort of verbal spectacle, doing the same thing to language that Siegel and Shuster did for the comics page.

These genres are clearly natural fits for each other in practice, but what is it that enables them to work so well together? More broadly, why does genre-crossing work in the first place? First it is necessary to understand genre, a word with two distinct but related meanings. In a classical sense, at least, genre describes structure as much as content. This is true even to the extent that Aristotle, in The Poetics, discussing how epics are distinct from tragedies not just in their plot structure, but in the fact that epics are written in hexameter. That

In the early 20th century this sort of approach to genre was in vogue through a set of critics known as structuralists. Structuralists were interested in describing things in terms of larger, often deterministic structures.

Aristotelean plotting, summarized briefly, and incorporating several developments postdating Aristotle himself, works thusly: a plot should follow a single action, albeit a complex action in which a character goes through several moments of “recognition and reversal” in which they learn something and, accordingly, have their fate reversed. Events at the beginning of the story should make events at the end likely, while events at the end should justify the inclusion of events at the beginning, a rule succinctly restated by Anton Chekov, who orders writers to “remove everything that has no

...more

By watching an imitation of a tragic downfall, in Aristotle, we are able to engage with the emotions of pity and fear in a cathartic, cleansing way that produces a spiritually validating feeling that is poorly captured by Aristotle’s prose, which is, in practice, merely the adapted lecture notes taken by his students at the Lyceum.

This gets at the limitations of the epic/pulp format - they are by and large suitable for storytelling based around what Aristotle calls spectacle, but rather lacking in most other regards. They’re fantastic if what you want is space combat (or some other form of exciting action and spectacle), but visibly lacking in character depth or in complex plotting.

comics are a medium that is, in practice, naturally inclined towards pulp genres. In many ways the War is fought over that inclination, and, more to the point, over a desire to reverse and resist that inclination, writing stories that are on the one hand using genre iconography associated with the pulps, but that are structured like literary fiction, and, ideally, that are widely recognized as literary fiction.

But a byproduct of the War was a massive profusion in techniques to accomplish literary-structured fiction with pulp iconography within visual media, many of which led to enormously successful films mostly (though not entirely) featuring American superheroes. Inasmuch as the War can be explained simply as the product of developments in what might be broadly described as “aesthetic technology,”

Moore’s position, in other words, is not that there is anythingwrongwith hisSoundswork as such, but rather that he simply doesn’t see it as appropriate to profit off of it given that he was still learning how to do comics. (Moore made a similar stand much earlier in his career, in fact, when he donated his proceeds for Acme Press’sMaxwell the Magic Cat reprints to Greenpeace, joking that “the guilt at having been paid twice for this stuff would honestly be more than I could bear, and I would almost certainly burn in hell forever.”)

On the one hand, Crumb is an immaculately talented artist who combines expressive naturalism with a fluid, cartoonish elasticity that lets him move seamlessly from the intensely human to the perversely grotesque.

Art Spiegelman, whose collection of the first few installments ofMausis typically grouped with Frank Miller’sThe Dark Knight Returnsand Moore and Dave Gibbons’sWatchmenin arguing for the idea that 1986 was the annus mirabilis of comics.

As he put it, “LSD was an incredible experience… it hammered home to me that reality was not a fixed thing. That the reality that we saw about us every day was one reality, and a valid one - but that there were other, different perspectives where different things have meanings that were just as valid.”

The tone of his praise in “Too Avant Garde for the Mafia” is telling - when he praises artists, it’s for things like being “creatively self-conscious in his use of the medium,” and the moments he chooses to single out are things like the final images of a biography of Stalin: “The narrative caption boxes relate how, during his final years, Stalin would travel by car along highways built for his solitary personal use across Russia. Wherever he stopped along the way there would be a room waiting for him specially constructed so as to be an exact duplicate of his room in the Kremlin, right down

...more

Arts Lab scene that was cropping up throughout the UK at the time.

Among the songs Moore contributed toAnother Suburban Romancewas a recycled version of a song he’d written in 1973, “Old Gangsters Never Die.” This, then, is the first piece of Moore’s work to become at all famous or well-known - a rendition of it served as the B-side to the 1983 release of “March of the Sinister Ducks,” which was also accompanied by an eight-page comic adaptation by Lloyd Thatcher. The rendition was used in turn for the 1987 episode of Central’sEngland Their England. The song had a second comics adaptation overseen by Antony Johnston and drawn by Juan Jose Ryp by Avatar Press

...more

Gilles de Rais was a 15th century French nobleman and ally of Joan of Arc, who, over the last eight years of his life killed upwards of eighty children

(It is worth clarifying for the sake of some readers that theDennis the Menacestrip inThe Beanois a completely separate phenomenon from the Hank Ketcham-created American comic strip of the same name. Both feature the same basic premise - a young boy named Dennis and his troublemaking exploits - although the American Dennis is a well-meaning child who inadvertently causes trouble, whereas the British one, created by artist Davey Law andBeano editor Ian Chisholm, is more of an unreconstructed sociopath. The two characters are wholly unrelated, with Law/Chisholm and Ketcham hitting on the name

...more

This approach is typical ofMaxwell the Magic Cat - even during the sections where Moore reworks it into being a political satire, the basic joke is typically the level of remove between what’s depicted in the strip and the cultural subject matter being joked about - for instance, a strip mocking the upcoming wedding of Prince Andrew is done in the form of Maxwell talking on the phone to (presumably) the Queen about his idea for “Andy and Fergy Airsickness Bags.”

Similarly, his discussion of process is telling. “For six pages,” he explains, “I’m usually thinking about thirty-three to thirty-five frames. I then get an ordinary spiral-bound note book and write out the number one to thirty-three, giving each number a separate line, and start to break the story down into pictures.”

As Steve Moore puts it, “if Dez asks for six pages, you give him six… the same as some editors will ask you for a set number of frames… and if they say forty frames, they don’t mean thirty-nine or forty-one. If you turn up saying ‘Sorry, boss, I couldn’t fit it in so I’ve used four extra frames’ then that, quite simply, is bad writing.”

Extra-dimensional beings playing games with the fundamental forces of the universe aren’t in and of themselves innovative, but throwing them into the universe of Star Wars is not only innovative is a witty commentary on the limitations of that universe.

tight little five-pager with a clear setup and punchline; on page one Leia encounters a Stormtrooper helmet and a pile of bones that, impossibly, look like they’ve been around for millennia. At the end the Stormtroopers pursuing her are accidentally sent millennia into the past by Splendid Ap, who is, as the narration notes, confused by time and space. The closing two panels feature Leia recovering and making her way back towards her ship, the Stormtrooper bones lying in the dust, neatly tying off the story’s premise and setup. Structurally it’s as straightforward an execution of the

...more

chronological history of Moore’s work in this period is difficult, requiring as it does several passes over the same few years. Further complicating it is the Warrior material - even though Moore broke with Warrior not long before its demise in early 1985, all of the comics he had been writing for Warrior survived, with two of them jumping with Moore to America. And, of course, as of 1983 his career included a sizable US component that rapidly came to provide a majority of his income and take up an increasing share of his time, making it impossible to differentiate cleanly between UK and US

...more

The Ballad of Halo Jones, which marks a significant dividing line in both Moore’s career and the War. Its abandonment in April of 1986 marks the point at which Moore’s work in the mainstream British comics industry ceases, and thus marks a clear transition. Furthermore, a month after the third book of The Ballad of Halo Jones wrapped in April of 1986 the first major battle of the War broke out with the publication of Watchmen #1 by DC Comics.

The first issue, or prog (short for “programme,” as the covers refer to themselves) of 2000 AD was cover-dated February 26th, 1977, but the history of the magazine begins slightly earlier, in 1974.

debuted Warlord. Warlord was a shot in the arm for an essentially moribund British boys comics industry in which there had been few major innovations since Eagle in 1950.

The strip, in other words, is an aggressive satire of what would become known as the broken windows theory of policing, in which focusing on small crimes against the social order - vandalism being the textbook example - was believed to reduce crime in general. In practice, of course, broken window policing became an excuse for police forces to focus on petty crime committed by poorer people, and was little more than an excuse for neoliberal crypto-fascists like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher to arrest more racial minorities. Dredd predates both Thatcher’s Britain, which came into power in

...more