More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But I wasn't told what these other mothers and fathers were told, that their sons were dead at the hands of a murderer. Instead, I was told that my son was the one who had murdered their sons.

I found it difficult, as I have always found it difficult, to read the exact emotional state of another person, and during this time, I certainly found it difficult to read Joyce.

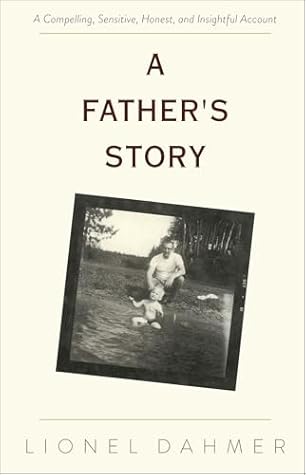

Joyce had said, "You have a son." And so I did. A son I would later name for myself. Jeffrey Lionel Dahmer.

I often think of him in that initial innocence. I imagine the shapes he must have seen, the blur of moving colors, and as I recall him in his infancy, I feel overwhelmed by a sense of helpless dread.

But when I tried to analyze her situation, I always reached a wall I couldn't climb.

What could I possibly do about her past? How could I make up for it? What could Joyce do about it, other than finally put it behind her? In my view, the point was to forget whatever fear or cruelty she'd experienced as a child, and to concentrate on the future. It seemed simple to me, clear and uncomplicated. You either overcame difficulties, or you were crushed by them.

particularly regarding my relationship with Joyce, things were more obscure and complicated. It was often hard for me to know exactly where I stood, or what I should do at any particular moment.

As it spread its wings and rose into the air, we, all of us— Joyce, Jeff, and myself—felt a wonderful delight. Jeff's eyes were wide and gleaming. It may have been the single, happiest moment of his life.

It was once nothing more than a rather sweet memory of my little boy, but now it has the foretaste of his doom, and comes to me, as it often does, on the thin edge of a chill.

Now, when I think of these discarded things, they take on a deep metaphorical significance for me. They are the small, ultimately ineffectual offerings I made in the hope of steering my son toward a normal life.

Jeff seemed completely disengaged. He never talked about the future, and I think now that he never believed that he actually had one.

Worse, I felt that I had used up a good portion of my life fighting to save a marriage which I should have recognized as doomed almost from the beginning.

We spoke, but we did not converse. I made suggestions. He accepted them. He gave excuses. I accepted them.

This dreadful silence we called peace.

By the fall of 1988, there were far, far more things that I did not know about my son than I did know about him. Certainly, I didn't know that he had already killed four human beings, two of them in the basement of my mother's house. But in addition to such horrible, nearly incomprehensible knowledge, I didn't know that he had been twice arrested for indecent exposure, first in 1982, then in 1986.

In my view, it was my son's dependence on alcohol that weakened his will to resist these other, even more dangerous and destructive impulses.

“Sorry," he repeated. Sorry? But for what? For the men he had killed? For the anguish of their relatives? For the torment of his grandmother? For the ruin of his own family? There was no way to tell exactly what Jeff was sorry for.

He lived in a world behind his eyes. I could never enter that world. We would always be separated by the barrier of his mental illness. In a sense, I saw nothing but his insanity.