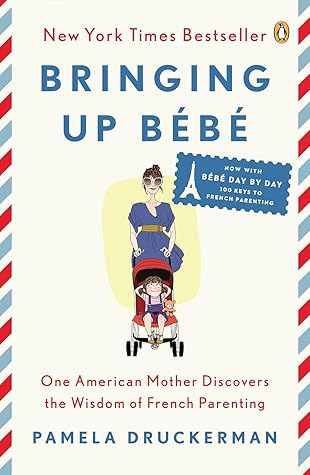

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 15 - November 15, 2023

When I ask French parents how they discipline their children, it takes them a few beats just to understand what I mean. “Ah, you mean how do we educate them?” they ask. “Discipline,” I soon realize, is a narrow, seldom-used category that deals with punishment. Whereas “educating” (which has nothing to do with school) is something they imagine themselves to be doing all the time.

France trumps the United States on nearly every measure of maternal and infant health. The infant mortality rate is 57 percent lower in France than it is in America. According to UNICEF, about 6.6 percent of French babies have a low birth weight, compared with about 8 percent of American babies. An American woman’s risk of dying during pregnancy or delivery is 1 in 4,800; in France it’s 1 in 6,900.1

Frenchwomen don’t see pregnancy as a free pass to overeat, in part because they haven’t been denying themselves the foods they love—or secretly binging on those foods—for most of their adult lives. “Too often, American women eat on the sly, and the result is much more guilt than pleasure,” Mireille Guiliano explains in her intelligent book French Women Don’t Get Fat. “Pretending such pleasures don’t exist, or trying to eliminate them from your diet for an extended time, will probably lead to weight gain.”

“My first intervention is to say, when your baby is born, just don’t jump on your kid at night,” Cohen says. “Give your baby a chance to self-soothe, don’t automatically respond, even from birth.”

Another reason for pausing is that babies wake up between their sleep cycles, which last about two hours. It’s normal for them to cry a bit when they’re first learning to connect these cycles. If a parent automatically interprets this cry as a demand for food or a sign of distress and rushes in to soothe the baby, the baby will have a hard time learning to connect the cycles on his own. That is, he’ll need an adult to come in and soothe him back to sleep at the end of each cycle.

She sometimes waited five or ten minutes before picking them up. She wanted to see whether they needed to fall back to sleep between sleep cycles or whether something else was bothering them: hunger, a dirty diaper, or just anxiety.

One rule on the handout was that parents should not hold, rock, or nurse a baby to sleep in the evenings, in order to help him learn the difference between day and night. Another instruction for week-old babies was that if they cried between midnight and five A.M., parents should reswaddle, pat, rediaper, or walk the baby around, but that the mother should offer the breast only if the baby continued crying after that.

“Enjoy” is an important word here. For the most part, French parents don’t expect their kids to be mute, joyless, and compliant. Parents just don’t see how their kids can enjoy themselves if they can’t control themselves.

“The mothers who really foul it up are the ones who are coming in when the child is busy and doesn’t want or need them, and are not there when the child is eager to have them. So becoming alert to that is absolutely critical.”

making kids face up to limitations and deal with frustration turns them into happier, more resilient people. And one of the main ways to gently induce frustration, on a daily basis, is to make children wait a bit. As with The Pause as a sleep strategy, French parents have homed in on this one thing. They treat waiting not just as one important skill among many but as a cornerstone of raising kids.

The first is that, after the first few months, a baby should eat at roughly the same times each day. The second is that babies should have a few big feeds rather than a lot of small ones. And the third is that the baby should fit into the rhythm of the family.

Dolto’s core message isn’t a “parenting philosophy.” It doesn’t come with a lot of specific instructions. But if you accept that children are rational as a first principle—as French society does—then many things begin to shift. If babies understand what you’re saying to them, then you can teach them quite a lot, even while they’re very young. That includes, for example, how to eat in a restaurant.

Rather, Dolto insisted that the content of what you say to a baby matters tremendously. She said it was crucial that parents tell their babies the truth in order to gently affirm what the babies already know.

Part of keeping the mood light is keeping the meal brief. Fanny says that once Lucie has tasted everything, she’s allowed to leave the table. The book Votre Enfant says a meal with young kids shouldn’t last more than thirty minutes. French kids learn to linger over longer meals as they get older. And as they start going to bed later, they eat more weeknight dinners with their parents.

American parents like me often view imposing authority in terms of discipline and punishment. French parents don’t talk much about these things. Instead, they talk about the éducation of kids.

At bedtime you can really see the French balance between being very strict about a few things and very relaxed about most others. A few parents tell me that at bedtime, their kids must stay in their rooms. But within their rooms, they can do what they want.