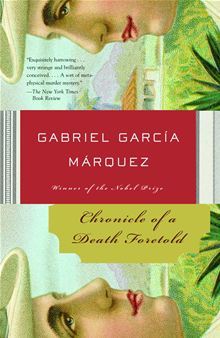

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 18 - September 18, 2023

Many people coincided in recalling that it was a radiant morning with a sea breeze coming in through the banana groves, as was to be expected in a fine February of that period. But most agreed that the weather was funereal, with a cloudy, low sky and the thick smell of still waters, and that at the moment of the misfortune a thin drizzle was falling like the one Santiago Nasar had seen in his dream grove.

The death of his father had forced him to abandon his studies at the end of secondary school in order to take charge of the family ranch. By his nature, Santiago Nasar was merry and peaceful, and openhearted.

“My son never went out the back door when he was dressed up.” It seemed to be such an easy truth that the investigator wrote it down as a marginal note, but he didn’t include it in the report.

“I didn’t warn him because I thought it was drunkards’ talk,”

Divina Flor confessed to me on a later visit, after her mother had died, that the latter hadn’t said anything to Santiago Nasar because in the depths of her heart she wanted them to kill him. She, on the other hand, didn’t warn him because she was nothing but a frightened child at the time, incapable of a decision of her own, and she’d been all the more frightened when he grabbed her by the wrist with a hand that felt frozen and stony, like the hand of a dead man.

Someone who was never identified had shoved an envelope under the door with a piece of paper warning Santiago Nasar that they were waiting for him to kill him, and, in addition, the note revealed the place, the motive, and other quite precise details of the plot.

They were twins: Pedro and Pablo Vicario.

“It was a strange insistence,” Cristo Bedoya told me. “So much so that sometimes I’ve thought that Margot already knew that they were going to kill him and wanted to hide him in your house.”

Many of those who were on the docks knew that they were going to kill Santiago Nasar.

No one even wondered whether Santiago Nasar had been warned, because it seemed impossible to all that he hadn’t.

Angela Vicario, the beautiful girl who’d gotten married the day before, had been returned to the house of her parents, because her husband had discovered that she wasn’t a virgin. “I felt that I was the one who was going to die,” my sister said. “But no matter how much they tossed the story back and forth, no one could explain to me how poor Santiago Nasar ended up being involved in such a mix-up.” The only thing they knew for sure was that Angela Vicario’s brothers were waiting for him to kill him.

“To warn my dear friend Plácida,” she answered. “It isn’t right that everybody should know that they’re going to kill her son and she the only one who doesn’t.”

“So much the better,” he said. “That makes it easier and cheaper besides.” She confessed to me that he’d managed to impress her, but for reasons opposite those of love. “I detested conceited men, and I’d never seen one so stuck-up,” she told me, recalling that day.

The brothers were brought up to be men. The girls had been reared to get married. They knew how to do screen embroidery, sew by machine, weave bone lace, wash and iron, make artificial flowers and fancy candy, and write engagement announcements.

“Any man will be happy with them because they’ve been raised to suffer.”

Angela Vicario only dared hint at the inconvenience of a lack of love, but her mother demolished it with a single phrase: “Love can be learned too.”

“Santiago Nasar,” she said.

“We killed him openly,” Pedro Vicario said, “but we’re innocent.” “Perhaps before God,” said Father Amador. “Before God and before men,” Pablo Vicario said. “It was a matter of honor.”

“We’re going to kill Santiago Nasar,” he said. Their reputation as good people was so well-founded that no one paid any attention to them. “We thought it was drunkards’ baloney,” several butchers declared, just as Victoria Guzmán and so many others did who saw them later.

“They looked like two children,” she told me. And that thought frightened her, because she’d always felt that only children are capable of everything.

“I knew what they were up to,” she told me, “and I didn’t only agree, I never would have married him if he hadn’t done what a man should do.” Before leaving the kitchen, Pablo Vicario took two sections of newspaper from her and gave them to his brother to wrap the knives in. Prudencia Cotes stood waiting in the kitchen until she saw them leave by the courtyard door, and she went on waiting for three years without a moment of discouragement until Pablo Vicario got out of jail and became her husband for life.

She taught us much more than we should have learned, but she taught us above all that there’s no place in life sadder than an empty bed.

“We’re going to kill Santiago Nasar,” he told him. My brother doesn’t remember it. “But even if I did remember, I wouldn’t have believed it,” he told me many times. “Who the fuck would ever think that the twins would kill anyone, much less with a pig knife!” Then they asked him where Santiago Nasar was, because they’d seen the two of them together, and my brother didn’t remember his own answer either.

In addition, the dogs, aroused by the smell of death, increased the uneasiness. They hadn’t stopped howling since I went into the house, when Santiago Nasar was still in his death throes in the kitchen and I found Divina Flor weeping in great howls and holding them off with a stick. “Help me,” she shouted to me. “What they want is to eat his guts.”

“That is to say,” he told me, “he had only a few years of life left to him in any case.”

Colonel Lázaro Aponte, who had seen and caused so many repressive massacres, became a vegetarian as well as a spiritualist.

Disproportionate eating was always the only way she could ever mourn and I’d never seen her do it with such grief.

They’d gone three nights without sleep, but they couldn’t rest because as soon as they began to fall asleep they would commit the crime all over again. Now, almost an old man, trying to explain to me his condition on that endless day, Pablo Vicario told me without any effort: “It was like being awake twice over.” That phrase made me think that what must have been most unbearable for them in jail was their lucidity.

For the immense majority of people there was only one victim: Bayardo San Román.

Most of all, he never thought it legitimate that life should make use of so many coincidences forbidden literature, so that there should be the untrammeled fulfillment of a death so clearly foretold.

“The strange thing is that the knife kept coming out clean,” Pedro Vicario declared to the investigator. “I’d given it to him at least three times and there wasn’t a drop of blood.”