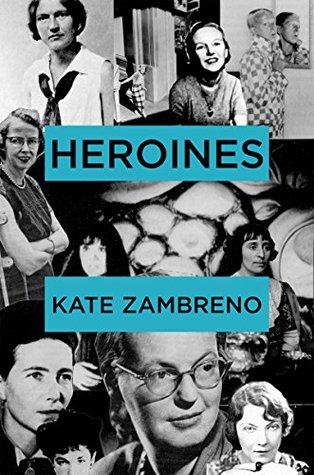

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I distrust the Feminine in literature,” T.S. Eliot once opined. A fear of the feminine in writing—of the hysterical, the emotional, the violent. Much as we fear women’s rage and tears. In Eliot’s essay on Hamlet in which he coins the phrase “objective correlative,” he writes, “Hamlet (the man) is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, because it is in excess of the facts as they appear.” His theories of depersonalization form the foundation of the theoretical school called New Criticism, still the fundamental ideology governing how we read and talk about writing. One cannot portray

...more

A definition, I think, of being oppressed, is being forbidden to externalize any anger. I am beginning to realize that the patriarch decides on the form of communication. Decides on the language. The patriarch is the one who rewrites.

I use the term “madness” here to describe these women’s alienation, because I see their breakdowns as a philosophical experience that is about the confinement, or even death, of the self.

Yet both the Surrealist aesthetic of automatic writing, as well as the theories of fiction that came out of modernism, seem to suggest that the woman’s radical spoken utterances are not art or writing in and of themselves, rather that an author is needed to edit and repeat, to shape and discipline.

The Great Men fetishized the hysteric, they channeled hysteria, both in style (automatic writing), as well as in their writing of these female characters,

yet in their material lives these men were not objects, but authors, subjects. I see this as a slumming. They fetishized the actress-hysteric, the spastic flapper-girl, the witty mystic, the lovely mental patient, they sucked her bone-dry.

These men, fetishizing and vampirizing the excessive (in their texts) while disciplining and punishing her in real life.

Schizophrenia, which both Zelda and Lucia were diagnosed with, was originally a catch-all category like hysteria. Later aspects of the diagnosis were channeled into other classifications with future permutations of the DSM. (A woman who would have been diagnosed as schizophrenia in the 20s-50s would in the 80s be much more likely to be diagnosed as bipolar or borderline personality disorder, because of new subclassifications in the DSM-III.)

The Fitzgerald flapper is tale-teller, not author. Like a medieval mystic needing a male confessor (his Princeton hero Amory reading St. Teresa of Avila in This Side of Paradise). The masculine modernist process of creation (author/muse), mirrors not only the mystic-confessor relationship but also the doctor-patient relationship in the Freudian talking cure (in all three binaries, she is the raw material, who needs to be shaped and coaxed into a narrative, she spurts forth, she needs to be contained).

Yet in Fitzgerald’s novel, as in real-life cases of these modern wives and mistresses, the woman’s “disordered language” is also used to convict her, to diagnose and name her—“Diagnostic: Schizophrenie.” The “case” is not an author, and so the letters, inspired by Zelda’s letters, are viewed not only as diagnostic examples but also the raw material for the book about the patient-wife that Dick is trying to write (the case

study of a psychoanalyst, standing in for a novelist, although still with the resulting writer’s block which mirrors the one in real life, Fitzgerald taking nine years to finish Tender while Zelda wrote her version of their marriage and their life on the French Rivera in months, it unfurling from her).

This is the narrative written about Zelda. It’s never disputed: this diagnostic label, schizophrenic. Or if it’s disputed, it’s seen as something else (she was bipolar, or BPD, not schizophrenic) with no awareness of these diagnostic labels as discursive categories.

The story of Zelda’s attempts to write Waltz can be read as a cautionary tale of the muse who takes herself, her breakdown, as her own material. For Waltz is not only about Alabama attempting to become a dancer, but also Zelda, through writing the work, trying to become a writer, to take back herself from being a character.

We live in a culture that punishes and tries to discipline the messy woman and her body and a literary culture that punishes and disciplines the overtly autobiographical (for being too feminine, too girly, too emotional).

The madwomen of modernism have been named—diagnosed—and this diagnosis, this demonology has been endlessly repeated through how they have been documented, written about, and read. The codes of identity in psychiatry have molded their identity in literature, as characters and authors, and this extends also to how we read women in general, and to how women read and write themselves.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman struggled with depression so the story must be her diary. When you reduce an author or character’s torment to a diagnostic category you are not allowing her the existential alienation of a novelist-hero, but the narcissism of a heroine.

I am beginning to realize that taking the self out of our essays is a form of repression. Taking the self out feels like obeying a gag order—pretending an objectivity where there is nothing objective about the experience of confronting and engaging with and swooning over literature. The comments on Frances Farmer Is My Sister and allied blogs that have built sometimes to this glorious other text, this communion, this conversation, this casual liquidness, the superlative nature, that is generative and affirming as opposed to dismissive, that uses our own language instead of theirs.