More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

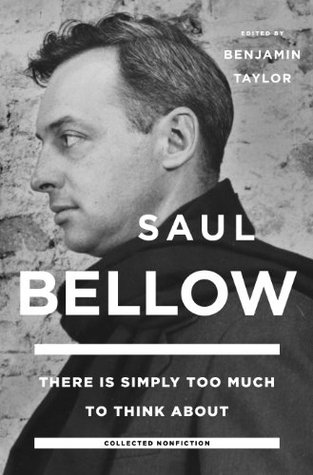

Saul Bellow

Read between

July 23 - August 17, 2021

I believe simply in feeling. In vividness. Where feeling is synthetic, ideals of greatness are merely dismal. Only feeling brings us to conceptions of superior reality. A point of view like mine is not conducive to popular success.

As a novel, Mottel the Cantor’s Son is not entirely successful; it is loosely constructed and undramatic, but it contains more remarkable characters than any five ordinary novels and it has its pages of incomparable comedy.

The stories of Mr. Roth show the great increase of the power of materialism over us.

Distraction is one of the subjects of Tolstoy’s masterpiece. Society is in Tolstoy’s view a system of distractions.

Art is the speech of artists. The rules are not the same as those in science and philosophy. No one knows what the power of the imagination comes from or how much distraction it can cope with.

even the so-called years of peace have been years of war. The buying and consumption of goods that keep the economy going, the writer sitting in his room may envision as acts of duty, of service, of war. By our luxury we fight too, eating and drinking and squandering to save our form of government, which survives because it produces and sells vast quantities of things. This sort of duty or service, he thinks, may well destroy our souls.

The greatest danger, Dostoyevsky warned in The Brothers Karamazov, was the universal anthill. D. H. Lawrence believed the common people of our industrial cities were like the great slave populations of the ancient empires.

To certain writers Christianity itself has appeared to be an invention of Jewish storytellers whose purpose has been to obtain victory for the weak and the few over the strong and the numerous.

one Jewish writer (Hyman Slate in The Noble Savage) has argued that laughter, the comic sense of life, may be offered as proof of the existence of God. Existence, he says, is too funny to be uncaused.

In literature we cannot accept a political standard. We can only have a literary one.

To see things as they really are, as we meet them daily, unthinkingly, is curiously startling.

among those seeking sainthood or martyrdom in traditional form he sees only illusion; not sacrifice but a perverse desire for pain; not love but self-will.

in both poetry and love, reality is what is created, not the raw material for the creation.”

“Give all to love,” they read in Emerson. But in City Hall there were other ideas on giving and we had to learn (if we could) how to reconcile high principles with low facts.

No less than Whitman, our Dirties, the Beats, offer themselves to their countrymen as exemplary types. They want their brethren, especially of the middle class, to express themselves more freely, more truthfully, to widen their horizons, to resist the drudgery of vacant duties and rebel against the servitude of banal marriage and unpleasurable sex.

If a novelist is going to affirm anything, he must be prepared to prove his case in close detail, reconcile it with hard facts, and he must even be prepared for the humiliation of discovering that he may have to affirm something different. The facts are stubborn and refractory and the art of the novel itself has a tendency to oppose the conscious or ideological purposes of the writer, occasionally ruining the most constructive intentions. But then, constructive intentions also ruin novels.

as long as novelists deal with ideas of good and evil, justice and injustice, social despair and hope, metaphysical pessimism and ideology, they are no better off than others who are involved cognitively with these dilemmas.

She quickly discerned the inordinate powers of Congressional committees, the dangers of bureaucracy, the complacency of the public toward graft, the power of business in government. She noted “the American contempt for the vested interest or ‘established expectations’ of the individual citizen.

Mrs. Webb’s high-mindedness here is redeemed only by her remark about polygamy: “Only one bull is required for twenty cows.”

Shunning extremes, he concentrates upon the average. This, however, he investigates in depth, and fixing his attention on matters entirely human he emerges with a new conception of the scope and meaning of a personal existence. Man lives on this earth, his life is fragile, his time is short; still, he enjoys many remarkable powers and he may acquire a profound skeptical wisdom.

The large claims made for the self in the early period of romanticism begin to sound foolish in the modern age of large populations. To men of acute intelligence, by the second half of the nineteenth century, romantic individualism began to appear fraudulent.

A few become activists and fly around the country demonstrating or remonstrating. They are able to do this in a free and prosperous America. I speculate sometimes about the economics of militancy. There must be a considerable number of people with small private incomes whose lifework is to march in protest, to picket, to be vocal partisans.

the rejection of thinking in favor of wishful egalitarian dreaming takes many other forms. There is simply too much to think about.

many of the material objectives of the Founders had been successfully realized.

The objectives of Lenin’s revolution never materialized in Russia, but they are all about us here in bourgeois America, says the philosopher Alexandre Kojève. In the process, everything worth living for has melted away.

Our American world is a prodigy. Here on the material level the perennial dreams of mankind have been realized. We have shown that the final conquest of scarcity may be at hand. Provision is made for human needs of every sort. In the United States—in the West—we live in a society that produces a fairy-tale superabundance of material things. Ancient fantasies have been made real.

My first proposal is that we should take away all U.S. passports and prevent Americans from tourin’ foreign countries. That’ll restore the good name of the U.S. abroad.

through the reading of novels we come to know others with an intimacy otherwise unfelt.

There was something about radical ideology that resembled orthodoxy in that it was enforced by people who insisted rigidly on the legitimacy of their political position.

Pollock stands to Picasso as Ginsberg stands to Whitman and Pound: provincials aspiring to a status which their intrinsic gifts deny them. But the exact quality of their gifts does not matter: the whole momentum of our culture shares in this unearned aspiration and rewards its exemplars with the trappings of authenticity.”

the arts are dependent on the help of the social body and sociological interests are, up to a point, legitimate. It is only when critics clearly prefer sociology and cultural analysis to the arts that I turn away from them.

We see now why the interests of art critics do not lie in the arts themselves but in the intellectual activities suggested by the arts. The next question, although rhetorical, cannot be shirked: Do the intellectuals represent the intellect? The answer to this is a heavy sigh. Intellect must not be surrendered to the intelligentsia. The beginner must achieve independence of thought.