More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

She stood old and bent at the top of the bank, silently watching me go, one gnarled red hand raised in farewell and blessing, not questioning why I went.

It was a bright Sunday morning in early June, the right time to be leaving home. My three sisters and a brother had already gone before me; two other brothers had yet to make up their minds.

It was 1934. I was nineteen years old, still soft at the edges, but with a confident belief in good fortune. I carried a small rolled-up tent, a violin in a blanket, a change of clothes, a tin of treacle biscuits, and some cheese. I was excited, vain-glorious, knowing I had far to go; but not, as yet, how far. As I left home that morning and walked away from the sleeping village, it never occurred to me that others had done this before me.

Naturally, I was going to London, which lay a hundred miles to the east; and it seemed equally obvious that I should go on foot. But first, as I’d never yet seen the sea, I thought I’d walk to the coast and find it. This would add another hundred miles to my journey, going by way of Southampton. But I had all the summer and all time to spend.

None came. I was free. I was affronted by freedom. The day’s silence said, Go where you will. It’s all yours. You asked for it. It’s up to you now. You’re on your own, and nobody’s going to stop you. As I walked, I was taunted by echoes of home, by the tinkling sounds of the kitchen, shafts of sun from the windows falling across the familiar furniture, across the bedroom and the bed I had left.

The biscuits tasted sweetly of the honeyed squalor of home – still only a dozen miles away. I might have turned back then if it hadn’t been for my brothers, but I couldn’t have borne the look on their faces.

When darkness came, full of moths and beetles, I was too weary to put up the tent. So I lay myself down in the middle of a field and stared up at the brilliant stars. I was oppressed by the velvety emptiness of the world and the swathes of soft grass I lay on. Then the fumes of the night finally put me to sleep – my first night without a roof or bed. I was woken soon after midnight by drizzling rain on my face, the sky black and the stars all gone. Two cows stood over me, windily sighing, and the wretchedness of that moment haunts me still.

Now I came down through Wiltshire, burning my roots behind me and slowly getting my second wind; taking it easy, idling through towns and villages, and knowing what it was like not to have to go to work. Four years as a junior in that gaslit office in Stroud had kept me pretty closely tied. Now I was tasting the extravagant quality of being free on a weekday, say at eleven o’clock in the morning, able to scuff down a side-road and watch a man herding sheep, or a stalking cat in the grass, or to beg a screw of tea from a housewife and carry it into a wood and spend an hour boiling a can of

...more

I was lucky, I know, to have been setting out at that time, in a landscape not yet bulldozed for speed. Many of the country roads still followed their original tracks, drawn by packhorse or lumbering cartwheel, hugging the curve of a valley or yielding to a promontory like the wandering line of a stream. It was not, after all, so very long ago, but no one could make that journey today. Most of the old roads have gone, and the motor car, since then, has begun to cut the landscape to pieces, through which the hunched-up traveller races at gutter height, seeing less than a dog in a ditch.

Just a spire in the grass; my first view of Salisbury, and the better for not being expected.

Southampton Town, on the other hand, came up to all expectations, proving to be salty and shifty in turns, like some ship-jumping sailor who’d turned his back on the sea in a desperate attempt to make good on land.

It was now or never. I must face it now, or pack up and go back home. I wandered about for an hour looking for a likely spot, feeling as though I were about to commit a crime. Then I stopped at last under a bridge near the station and decided to have a go. I felt tense and shaky. It was the first time, after all. I drew the violin from my coat like a gun. It was here, in Southampton, with trains rattling overhead, that I was about to declare myself.

All in all, my apprenticeship proved profitable and easy, and I soon lost my pavement nerves. It became a greedy pleasure to go out into the streets, to take up my stand by the station or market, and start sawing away at some moony melody and watch the pennies and halfpennies grow.

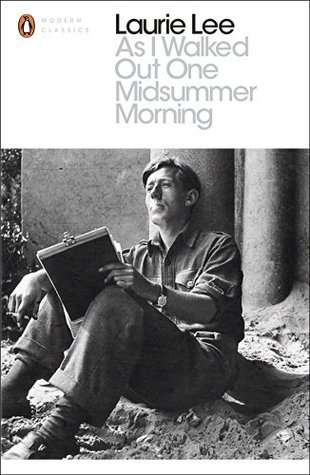

Already I felt like a veteran, and on my way out of town I went into a booth to have my photograph taken. The picture was developed in a bucket in less than a minute, and has lasted over thirty years. I still have a copy before me of that summer ghost – a pale, oleaginous shade, posed daintily before a landscape of tattered canvas, his old clothes powdered with dust. He wears a sloppy slouch hat, heavy boots, baggy trousers, tent and fiddle slung over his shoulders, and from the long empty face gaze a pair of egg-shell eyes, unhatched, and unrecognizable now.

I walked steadily, effortlessly, hour after hour, in a kind of swinging, weightless dream. I was at that age which feels neither strain nor friction, when the body burns magic fuels, so that it seems to glide in warm air, about a foot off the ground, smoothly obeying its intuitions. Even exhaustion, when it came, had a voluptuous quality, and sleep was caressive and deep, like oil. It was the peak of the curve of the body’s total extravagance, before the accounts start coming in.

I was living at that time on pressed dates and biscuits, rationing them daily, as though crossing a desert. Sussex, of course, offered other diets, but I preferred to stick to this affectation. I pretended I was T. E. Lawrence, engaged in some self-punishing odyssey, burning up my youth in some pitless Hadhramaut, eyes narrowing to the sandstorms blowing out of the wadis of Godalming in a mirage of solitary endurance.

One could pick out the professionals; they brewed tea by the roadside, took it easy, and studied their feet. But the others, the majority, went on their way like somnambulists, walking alone and seldom speaking to each other. There seemed to be more of them inland than on the coast – maybe the police had seen to that. They were like a broken army walking away from a war, cheeks sunken, eyes dead with fatigue.

Alf talked all day, but was garrulously secretive, and never revealed his origins.

I went round to the entrance, thinking I might get in, but was stared at by a couple of policemen. So I stared, in turn, at a beautiful woman by the gate, who for a moment paused dazzlingly near me – her face as silkily finished as a Persian miniature, her body sheathed in swathes like a tulip, and her sandalled feet wrapped in a kind of transparent rice-paper so that I could count every clean little separate toe.

No architectual glories, no towers or palaces, just a creeping insidious presence, its vast horizontal broken here and there by a gasholder or factory chimney. Even so, I could already feel its intense radiation – an electric charge in the sky – that rose from its million roofs in a quivering mirage, magnetically, almost visibly, dilating.