More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In Ireland, two years before, it had transpired that her husband, a contrarian, was born to drive on the wrong side of the road, while her mother, a worse contrarian—and whom she had defeated by marrying the former—planned to drag them all to hell that way.

“Wide load,” she heard her mother saying to the asses of the sheep, as if they were women.

The night flowed like just-struck oil outside the windows; she tried to fix the details of it in her mind.

Her pink lipstick, drawn far beyond the outline of her mouth, smiled without her.

Maybe the soul was just that dearness nestled in the center of the body, like a chosen pebble in the palm of a hand. When you held someone it was that dearness you felt, that chosenness.

He had done all this to rinse her sister’s mind of pain. Pain was one of the things he could not stand, along with muppets—“I can feel them getting dirty”—and receipts, which were endocrine disruptors.

She did what she always did in a car: looked out the window, trusted, and let herself be carried along.

Europeans, who knew which laws to disregard, were stripping off their clothes and swimming.

You could pose with a Red Bull next to the tallest waterfall and make it seem like you were peeing. A perfect place.

The balancing of the tallest cairns seemed to indicate that there were properties of physics we did not understand, or else they were overruled by the earth’s desire to be surprising.

It was strange to know that when something was really wrong with her, no one would be able to tell.

Their show had been canceled, she shouted, because of their embrace of the true faith! Her husband explained that they were Canadians, and Canadians didn’t have faith.

A year later, she would find herself obsessively revising 150 words she had written about this experience: the grave, the daffodils, the peeing in the glen—the church that was just a door in the air—but she could not make it mean anything, and she did not know why.

Some mornings she seemed true, and then she was I; some mornings she seemed false, and then she was she. And long after that, she could not even read the 150 words—it was like walking a path into a dark wood—or the feeling of madness would begin again: Who am I, what do I do? Could you resuscitate poetic logic, though it seemed to have died?

Isle Maree was famous for the Wish Tree, an oak that had been hammered so full of pennies that it had died of copper poisoning. Many things still stood that way, hammered full of wishes.

The first line of the mad notebook read “I wish, when I was a teenage Christian, that I had been more experimental with my evangelizing.

No one wants to read about any of this, and so she kept it hidden, and wrote everything down, and felt long scissoring strokes when she looked into it, and sometimes a high deafening dive.

And had fallen so far out of the world, out of the human population, that she could not even rejoin them to watch the butthole cut of Cats.

Sometimes she sat at the foot of the illness and asked it questions. Had it stolen her old mind and given her a new one? Had she been able to start over from scratch, a chance afforded to very few people? Had it optimized her?

Maybe that was fine. If she never formed another memory, then nothing could ever happen to her; if she never recognized another human face, she would never misplace another pair of blue eyes; if the weave of her had loosened to let time fall through at a more ecstatic velocity, maybe she would do nothing but rush and rush until the great gold boulder came and caught.

“I’m sorry not to respond to your email,” she wrote, “but I live completely in the present now.”

Before she learned of the existence of “alien hand syndrome,” she had tentatively diagnosed herself with a new illness called Who Foot Is That. The main symptom was gasping when you saw your own foot.

The CEO of Texas Roadhouse killed himself, no longer able to bear the continuous ringing in his ears. In his lengthy obituary, the newspaper printed the quote: “We’re a people company that just happens to serve steaks.”

“If you are not yourself,” the doctor in her mind asked, gently, “then what are you?” The world, she told him—it was obvious—undergoing an unprecedented bucatini shortage.

Proof that William Carlos Williams was a modern man was the fact that he named his son Kevin Carlos Williams. Kevin Carlos Williams!

The defining events of their time—9/11, for instance—had never properly entered into literature, because almost as soon as they happened they were transformed into propaganda. A writer of the age occasionally contrived to have a character die on 9/11 in a business suit, but there was nothing more embarrassing, though no one could quite say why.

Also, the people of her generation seemed unwilling to live in the small dusty corners of these dramatic happenings; they had to fly the whole plane into the buildings themselves. Perhaps the illness would be like that too. A writer would try to have the whole thing.

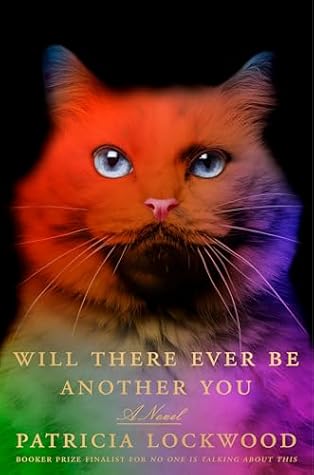

The same vendor offered another framed Time for sale. Yes, it was the one with the cloned sheep named Dolly, and the words Will there ever be another you?

Did she sound like herself? It was very important to sound like herself, she thought, and added another line that made it clear how much she now hated her father.

The time that was unbearable was when Tolstoy kept repeating: Everything was fine.”

“Any preexisting anxiety?” the doctor asked. “…No,” she said very quietly, though in fact she was the kind of child who was scared not only of the fireworks but of the half hour it took to find parking before the fireworks.

Write something sensual, she commanded herself, and after half an hour managed to produce the sentence: There were few compensations about the new life they were all leading, but daily headlines about coronavirus “lingering in the penis” were one.

“WHAT?” she yelled, the greatest word in the English language.

They passed a car with a bumper sticker that read Honk If You Miss Princess Diana. Her husband laid long and respectfully on the horn.

“It would be easy to be dead if I were French,” she thought, not for the first time.

He knelt in front of her with his head resting on her breastbone and she was surprised to feel his thighs shaking against her; despite his strength, he could hardly hold the pose either. So it was as difficult to persist in loving the replaced person as it was to be replaced.

she confessed to reading Craigslist Missed Connections at a time of great loneliness in her life. What if someone had seen her, across a crowded room? And thought, Her I must meet. That’s the one, as the photographers always said when they finally got the shot.

One quality of diarrhea is intense meteorism, she read. She did not have diarrhea. But she had the comet inside her that made her write that down.

The brain—trained to leap, only to discover its accustomed landing pads were gone.

And why be surprised? she wondered, surfacing from a long, lung-bursting dive that seemed to separate the old self from the new, with the light net of glitter on her skin that meant she was soon to catch something, some meaning.

if you were the only one who could see a plague, maybe it was directed at you.

When he took her author photo, he gave her directions like Look alive and Do something else with your face. Last time she had cried when he said Look alive, so then he changed it up and shouted, You’re a new grandma! and that was the shot they had used, the one people would see long after.

“That kind of ruled, though,” she said, which is how all these conversations ended. An age, whatever else you might say about it, really did kind of rule.

And what was the thing we had believed about Monet? “That he was a frog,” her husband had said; only a frog would know some of the things about lily pads that he knew.

He refused to make art himself, he said it was for crazy people.

Every morning for the next two weeks, he would say the same words, wide enough to include her: Those things are lasting forever.

grapefruit—he was a great believer in things wrong with the human body being exactly as large as fruits—but

and she thought, that is the lesson: You must live your life in such a way that your children do not laugh when you claim to have been attacked by an anti-papist Rottweiler.

“Wait, what happened to the puppies?” her husband asked. They had all been born with holes in their hearts. They were so unfit to live that she wondered if she weren’t one of them.

But what a relief, not to speak English. It was unzipping the body and stepping out. It was knocking the sharp corners off everything in the world. Certain rooms of drunkenness—whatever happened in them kept happening. Her crawling across the dirty floor of a diner, making friends with a dog.