More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Being seven years old, I was inclined to take notice of swear words—so I committed the word to my memory. I spent the next three years calling people atheists, having no clue what it meant, thinking I was a cutting trash-talker.

My teacher gave me an F on a spelling test, and I muttered, “What a freaking atheist.”

My mom made me go to bed early, and I screeched from the top of the stairs that I was living in a family of cold-blooded atheists.

don’t know what’s wrong with me. I’ve been exhausted. I don’t have the motivation to wake up in the morning, let alone the drive to go to a bookstore and interact with people.

I have to make money to pay my rent, and buy food to sustain my existence, because that is the purpose of my life.

I wonder what it’s like to be him. To vocalize the stupid thoughts he has without considering how others will interpret them. He just fumbles happily through his day, saying whatever he is compelled to—while I am over here laboring to produce appeasing facial expressions.

Just as I had removed my pants and begun inspecting the rest of the pants folded in my dresser drawers, assessing whether they too were weird, I heard Eli shout: “Are you fucking kidding me, Max? Look at your fucking pants! You wish my sister weren’t gay!”

“When did you come out?” Eleanor asked me. We were on our second date. I never know how to answer that question because I don’t feel like I am out. I feel like I am in a constant state of coming out, and like I always will be. I have to come out every time I meet someone.

Eleanor keeps texting me. I don’t feel comfortable responding at work because I’m worried Jeff and the Catholics will be able to sense I am doing something gay. Hello?

“I love your coat,” I compliment the stranger standing next to me. I had been mustering the courage to say it for the last ten minutes.

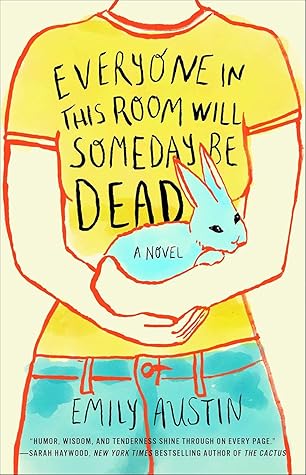

“Everyone in this room will someday be dead.”

Every dish I own is now on the floor of my bedroom. I find the prospect of collecting these dishes, let alone washing them, exceptionally daunting. Envisioning myself picking up even one cup knocks the wind out of me. I’d reached for a cup earlier, and it felt as if I’d run a marathon. I almost immediately fell asleep.

Whoever wrote this book prioritized men so much, he forgot about the other half of humanity. It seems like I can curse my parents with no repercussions at all.

Eleanor doesn’t struggle to fall asleep. Her head had hardly hit the pillow before her engine started revving up.

I find it so bizarre that I occupy space, and that I am seen by other people.

I can’t believe that I’m alive. Black. I can’t believe that I can believe anything.

I came to the realization that every moment exists in perpetuity regardless of whether it’s remembered. What has happened has happened; it occupies that moment in time forever. I was an eleven-year-old girl lying in the grass one summer. I knew in that moment that was true and recognized that I would blaze through moments for the rest of my life, forgetting things, and becoming ages older, until I forgot everything—so I consoled myself by committing to remember that one moment.

Everything matters so much and so little; it is disgusting.