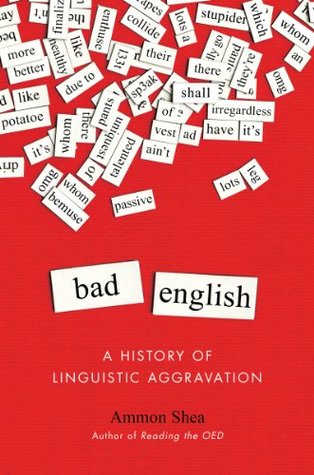

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Ammon Shea

Read between

July 27 - September 7, 2020

Anything that is worth fighting over is also worth celebrating. The aim of this book is to examine a number of the issues commonly thought of as mistakes in English usage and to see how these mistaken forms have been used over the past five hundred years in ways both eloquent and awkward.

According to those who sit up at night worrying about the state of our language, English has been headed to hell in a hand basket for a very long time.

there are but two things that have remained constant: The English language continues to change and a large number of people wish that it would not.

Our language is a glorious hodgepodge that is the result of invasion, exploration, linguistic inventiveness, and yes, simple error.

There has never been anything close to agreement about what exactly constitutes correct English usage.

I hope that this book will give you answers and allow you to make a decision about whether you want to continue to annoy language purists in the future.

grammar refers to the manner in which the language functions, the ways that the blocks of speech and writing are put together. Usage refers to using specific words in a manner that will be thought of as either acceptable or unacceptable.

The third-person neuter singular (they or their when used to refer to a single person of either sex) was in common and accepted use until the beginning of the nineteenth century,1 and is showing signs of making a resurgence.

Almost all words change their meanings. This is one of the aspects of language that is firmly established.

One of the things that is most curious about people who hold themselves up as language purists is that they seem to spend considerably more time complaining about language than they do celebrating it,

In April 2012, the Associated Press announced, “We now support the modern usage of hopefully,”1 which, in certain circles, was tantamount to saying “We now support beating baby seals to death with a copy of Webster’s Third New International Dictionary.”

Among people who might be described as having at least a passing regard for the English language, there are few instances of usage that evoke a desire to mutilate more than the perceived misuse of literally.

the Etymological Fallacy, a tendency to believe that a word’s current meaning should be dictated by its roots.

Judging by the fact that the broadened sense of the word has now been continually condemned for over a hundred years, it would appear that the people the language guides are directed at have not been paying attention.

The abuse of language and the abuse of people who do so are both part of the human condition.

We are looking for two things when we accept new meaning in an existing word: It must stand for a concrete action or thing, and its use must represent a dramatic shift in meaning.

In short, we are open to semantic inventiveness and resistant to semantic drift. The former represents a healthy form of ingenuity; an old word repackaged and applied to some new invention. The latter reminds us of something that is inexorably and gradually slipping away; our lost youth and vigor, as represented by the immutable mutability of language.

Most dictionaries today tend to view their role as that of recorder of language, rather than watchdog. If enough people use a word in a certain fashion, whether rightly or wrongly, then lexicographers will dutifully note this usage. Cocoa is universally accepted in dictionaries as referring to “a powdered form of the ground cacao bean used to make chocolate,” yet it is nothing more than a poor spelling of cacao that somewhere along the line managed to be misspelled by enough people to gain legitimacy.

Fruition likewise had a single meaning in English for several hundred years; it meant “enjoyment; the act of enjoying something” from the beginning of the fifteenth century until the twentieth. At the end of the nineteenth century, however, some language philistines confusedly assumed that it must have something to do with the ripening of fruit and began to use it in the sense of “to come to a desired result.” Use of fruition in this secondary sense now far outstrips its use in the former sense.

It is notable that writers and editors have not always been content to grant Shakespeare leniency in these matters. Alexander Pope, in editing the Bard’s works, was prone to removing double superlatives (as well as other instances of questionable syntax). In Julius Caesar, Pope changed the immortal line “this was the most unkindest cut of all” to the somewhat blander “This, this, was the unkindest cut of all,” rendering Antony grammatically correct but removing some of the essence of the line.

scientific terminology (which is obviously a domain populated by sadists with no regard for language).

The Eveready company, makers of flashlights, tried to extend their manufacturing range to language in 1917, when they offered the astonishing prize of $3,000 to whoever could come up with a better word for flashlight.

it is exceedingly unlikely that you, or anyone you know, will ever be able to create a word and see it have widespread use; that just isn’t how language works.

Although we do frequently see words introduced into the language (such as blog, staycation, and innumerable political scandals ending with the suffix -gate), such words usually do not survive for long and are generally not the result of an individual spontaneously deciding to create a word.

One of the reasons I have such a healthy skepticism for so many of the rules for and suggestions on the proper use of English is that when you look at many of the rules from a generation or two back, they often appear laughable.

And in- can also function as an intensifier, as in cases such as inflammable, which can mean “not capable of being set on fire” and also “very much capable of being set on fire.”

The most common complaint one hears about this word (and one hears it frequently) is that it “is not a word.” This is a curious statement to make since irregardless does in fact have what most of us would consider to be necessary components of a word—it is a series of letters arranged in a specific order, frequently used in either speech or writing, and indicating a commonly understood meaning.

some people have a suspicion that the verbing of nouns is peculiar to American speech or writing and, as such, somehow represents the continuing decline of English. It is a common practice in Great Britain to bemoan the pernicious influence that we Americans have had upon our mutual language.

If you attempted to keep your speech clear of any verbs that formerly were nouns you would be rendered unintelligible.

However, one small point is oft-overlooked in this continuing fight against the use of impact as a verb: it has existed as a verb for much longer than it has as a noun.

Friend has been used as a verb for about eight hundred years now, although befriend has always been more common. But be- prefixed words are on a decline in English (although words such as bewhiskered and bespattered still have some currency), and there is little likelihood of reversing this trend.

The suffix -ize is one of the most widely disliked in our language, as a result of having shown itself to be remarkably talented at attaching itself to old and respected words and creating new and disrespected ones.

There are a good number of people (although fewer now than fifty years ago) who still view using contact as a verb of any sort as problematic.

Contact continued to appear as a verb in the nineteenth century, generally in a technical sense, referring to such things as gunpowder or electricity coming into contact with something else. No one paid the word much mind. But then we Americans got our hands on the word and began to use it in an entirely inappropriate manner, referring to the practice of initiating communication with a person. After this all hell broke loose. Well, not quite, but a number of people became upset.

Unfortunately, we have not yet been able to nail down exactly what good grammar is.

our language persists in changing, and the people who use it persist in ignoring the grammar rules that they find unwieldy or awkward; in many cases this will cause the rules to change over time to accommodate this usage.

Many of the rules that we all think we should follow came from earlier grammarians, who were frequently armed with nothing more than a decent classical education and an abiding desire to correct the language of others.

According to some who thought long and hard about such matters, a grammatical error was a contradiction in terms (grammatical to them meant “having correct grammar” and so if it is an error it cannot be grammatical), and the preferred term should be an error in grammar.

As English spreads across the globe its variants become increasingly distinct from each other, yet for many there is a persistent belief that one true variant is grammatically correct.

You might be familiar with the voice-over from the beginning of the television show Star Trek (the original series), which contains the portentous phrase “To boldly go where no man has gone before.” It is sometimes held up as an example of misuse by those who track the split infinitive and would like to kill it. It is also proudly held up as an example of how an infinitive can be happily split.

An infinitive verb is widely considered to be the construction to + (verb), as in to criticize or to correct. Star Trek, in the eyes and ears of some, spat upon the English language in contempt when the writers inserted that boldly between the to and the go. Most linguists, however, refuse to accept this definition of the split infinitive, as they feel, rightly, that the word to is not actually part of the infinitive.