More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Mayra regarded Hialeah the way a gringa would: what a quaint little place, what potential. But I felt bad for people who lived anywhere else. Where else could you find a four-dollar medianoche the size of your head? Where else could you open a window and eavesdrop on three different conversations without even having to hold your ear to the screen? Where else, four beers deep, having come home after half-watching the Heat game at Flanigan’s happy hour, would you find a green anole perched on your showerhead, bobbing its head to the salsa blasting from a neighbor’s yard?

I knew she’d rather chug a pint of swamp water than ever come home, but I wanted to make her say it. “I’m actually driving. I’m in Gainesville these days.” “Gainesville? Since when? I thought you were up in Vermont or something.” That she’d never live near Miami again was a given, but even Gainesville, a five-hour drive north, seemed too close. I assumed the entire state of Florida, for her, had a repellent radius of at least five hundred miles.

I’m at UF now. Or I was,” she said. “So what do you think? I’ll get there tonight, and you can come anytime after that. Explore with me? Catch up?” “Maybe,” I said. There’d been a period of my life when I’d have done anything for that much alone time with Mayra. “Come on. When was our last sleepover? Think about it.” “I have work, though,” I said. “Where do you work these days? Can’t you take a day off?” I could.

“I work in real estate,” I said. “You’re an agent?” “Mhmm,” I answered. I was an assistant, but I didn’t want to demote myself in Mayra’s mind. “That means you, like, sell houses that’ll be underwater in twenty years?” So there was still no winning with her. “I guess, bro,” I said, “but it’s just a job. A lot of these assholes are so rich they buy these places and barely even live there, anyway.” “You have any tours scheduled tomorrow?” “No.”

Spend the weekend,” Mayra pressed. “I have a date tomorrow.” That was true. “A date! With who?” Her voice became low, conspiratorial. The tell me everything tone. Except there was nothing to tell. A middling man I’d matched with asked me on a first date, and I said yes, hoping he’d surprise me. “His name is Brian,” I said. “He’s amazing. I think it’s going really well. We’re still kind of in the honeymoon phase, so I’ve really been looking forward to tomorrow night.”

He enjoyed watching Westerns and going to the gym. Two beige flags. “And after the date?” she asked. “Can’t you come on Friday?” I said I’d think about it. “How about you let me give you directions now in case you do decide to come. I don’t know how good service will b...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

My phone would only get me so far, she said, and after that I’d have to follow the instructions I was jotting on a sticky note: left at a fork, five-mile stretch of swamp, left again at a marsh, and twenty-odd miles later a right onto a gravel road that was easy to miss. “See you soon, I hope,” she said.

For years, Mayra floated on the surface of my mind until, waterlogged, she finally sank to the bottom. Here she was again, risen from the deep, all smile and bite.

It’s a cruel trick of the universe that one can be exhausted after a day of mostly sitting still.

On days that will be documented, no one feels adequate in their own skin. Whoever we are, wherever we’re going, we figure our opposites would be better suited.

Think of prom night, when girls with straight hair get perms and those with curly hair iron it straight.

Who did she sound like? I couldn’t pin it down. Her new accent was unplaceable, I realized, because it wasn’t from any place in particular. A mixture of Miami and the Midwest, New York and California. A hodgepodge. A ransom note.

I-75 became Alligator Alley. All marshland, everywhere. In the span of one mile, I had entered another world. Sawgrass stretched all the way to the northern and southern horizons. Gators lounged on the roadside, indifferent to cars and the humans they carried. This wet chunk of Florida hummed with life. Beneath every still marsh, at the base of every tuft of sawgrass, there was a world of cranes and egrets, gators and turtles.

The sea of sawgrass gave way to cypress domes, which seemed as good a home as any. I could build a lean-to, subsist on fish and algae, and accidentally ingest some single-celled organism that would grant me perpetual youth.

A pack of black vultures studded the bare branches of a cypress, waiting, I supposed, for something to die. Gradually, the forest north and south of me thickened with palms and bright green cypress needles. The low sun leaked gold onto the landscape, and once it set, each car on that dark stretch glided in its own island of light.

A neon Hot Coffee sign blinked by the door. It was an oasis of sorts, the only sign of civilization for miles. In the empty aisles of the store, I yelled hello and was embarrassed by the quiet rasp of my voice. Treats wrapped in colorful plastic languished under buzzing lights. The packaging of a Cozmic Bar, a chocolate slab studded with multicolored candy bits, promised me I Wouldn’t Believe My Mouth.

“I was just saying the python is invasive,” he repeated, slower and louder. “Like all those iguanas. Or feral hogs.” He lifted his chin at his skinny friend. “You might see a few of those if you come with me. Scary motherfuckers. Fearless.”

“Well, drive slow out there,” Skinny said before I could confirm. “It’s dark. Go too fast, and there’s all kinds of animals you won’t see until they paint your windshield.”

I could either keep following the road or get back on Alligator Alley, I hesitated. I could turn right back around and retrace my way home, strip off this ridiculous outfit, and crawl into bed. It would certainly save me a headache. But for once I thought: Do what Mayra would do. Do what scares you.

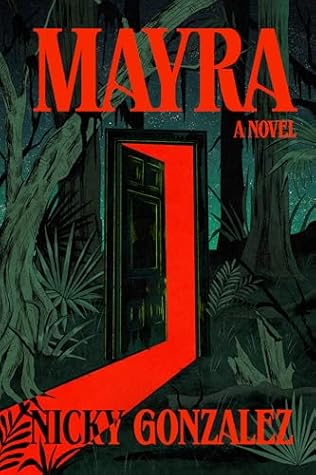

a gravel path for so long that I began to wonder whether it wasn’t a driveway at all, but another unmarked road, when at last I reached a small clearing. The headlights’ white halo fell onto brown shingles. Frogs leapt out of the beam. I cut the engine. A half-moon hovered over the massive shadow that was the house, a dark seashell shape against the sky, with a second floor slightly smaller than the first, topped by a pitched loft like a dollop of cream. Squares of soft light resolved into windows, the distance between which suggested a structure with impossible dimensions.

The front door opened, dropping light onto the wide wooden porch. There was Mayra, pajama-clad in the doorway, waving to me the way she used to—quick and close to the chest. She might judge me for drinking burnt gas station coffee, so I left it in the cupholder to stink up the car. I grabbed my bag and rushed to meet her. My arms lifted of their own accord, and I found myself wrapped around her. “Ingrid,” she said, hugging back. “You made it.” “I’m sorry,” I said, pulling away. “I guess I missed you.”

The McMansions I’d passed on the drive looked like a well-aimed leaf blower could send a whole row of them flying. The few I’d entered had been staged new constructions, Bath & Body Works Winterberry–scented purgatories with wide blank walls and unscuffed floors. The interiors, a blend of modern minimalism and Greek Revival, seemed to place them nowhere in time. They had no ghosts, no mold, no history.

There was a cavernous living room with plush red armchairs and a heavy carpet, the oldest kitchen I’d ever seen, with an iron stove and a water pump, another room with pale blue walls and green lounge chairs. Eventually, we found ourselves in another kitchen, much more modern, where the faint scent of onions lingered. Pots, skillets, funnels, and sieves hung above a butcher block island in the center of the room. The marble countertops looked so smooth and new I had to tamp down the urge to lick them corner to corner. “Two kitchens?” I asked. “Yeah. The other one is historic or something.

...more

It made sense that she felt at home in the woods, seeing as I’d always categorized her in my mind as a kind of wild animal.

The dresser mirror was splotched with silvery gray, and my reflection in it seemed to emerge from a storm cloud. All of my blemishes were blurred or erased, a beauty filter of sorts. In the green glass room, there are mirrors but no reflections. The phrase appeared in my mind unbidden. It had the musical cadence of a nursery rhyme and I tried to recall its origin. It took a moment to dredge up the memory of my classmate Laura, years ago, presenting me with a riddle: In the green glass room, there are feet but no hands. “In the green glass room, there are butts but no heads,” I replied.

“In the green glass room,” I said, “there are toes but no fingers.” She shook her head. “But there’s feet?” “Right,” she said. “And there are daffodils, but no daisies.”

The more clues she fed me, the more frustrated I became until, finally, I asked for a hint. Write them down, she said. Then the rule was obvious; only words with double letters were allowed in the green glass room. At lunch, I’d wasted no time testing Mayra. She went quiet after three clues, ripping her cafeteria cheese sticks into bite-sized pieces. A long moment later, she solved the riddle. No hints. No need to write anything down.

I only meant to lie down for a second, but, carried away by the swamp’s song, I slept all night.

Wind combed through the slash pines like breath into a lung. The trees leaned eagerly forward, waiting for the show to begin. Mayra caught me staring into the thicket. “Wanna go on a little hike?” she asked.

“Okay. Sure. Why not?” I was already way out in casa del carajo. I might as well get the lay of the land.

I often wonder what’s wrong with me. Before I was aware of the way anxiety could grip the body and wring it dry of joy, I named my ailment “the balloon.” The balloon is the extra organ inside of my chest that inflates of its own accord, plugs up my ears, and suffocates me from within. On bad days, my vision blurs. Nights when it feels like the balloon is swelling and crowding the blood and muscle, I roll onto the floor and do push-ups until it deflates. When that doesn’t work, I sleep with the TV set to anything at all. It doesn’t matter what, so long as it keeps my thoughts from veering

...more

I joked about no longer being the youngest patrons, but when I looked at Mayra, she was staring down at the pool table, frowning. I prodded her stomach with the end of a cue, and it was there, under a low-hanging Yuengling lamp, that Mayra finally confessed. “I applied to Cornell,” she said. “Remind me what that is?” I said, massaging a chalk cube onto my pool cue. “A college. In New York.” “I thought we were going to Dade?” That’s what we had decided, with both our butts squished into one computer lab chair, surfing the community college’s website.

“Can I ask you something?” “You probably have a lot of questions,” Mayra said. “Where did you go?” The silence that followed was not uncomfortable. I didn’t want to rush her. I focused on the rhythmic crunch of twigs beneath our shoes. The trees seemed to have dropped their leaves just for us, so our feet could land on soft carpet. In the green glass room, there are trees but no leaves. “I disappeared, didn’t I? I didn’t really know what to do with myself after undergrad.

I moved to a little town in Massachusetts as an assistant in an art museum.” “That sounds fun,” I said. “It was a job. But there are definitely less fun jobs.” I lifted my arm to show the wet stain there, dark gray against light gray. “You know what that is?” “Huh?” “A Rothko.” Mayra rolled her eyes.

Leaves and twigs and dead things crunched under our heels. In some places, the ground went squishy. I heard, but couldn’t see, critters rustling away. “Well, you weren’t wrong,” I said. “I also wasn’t employed. And for all I know I was wrong. Just because she was the director’s niece doesn’t mean she was inexperienced.” “Really, bro?” “Okay, fine. I might have been right about that.”

“But sometimes it’s hard to realize you’re having a hard time. In the moment you convince yourself you’re fine, and then you look back and realize you were barely staying afloat.”

Some people, while wonderful separately, were like fire and tinder when placed in the same room.

For the first time, I didn’t know what I was going to say before I said it, and I didn’t know until I said it that it was true.

Language had jumped ahead of me and peeled away the rind to reveal the soft, sour thought beneath it.

The more words you have for something, the closer you can get to the heart of it.”

She dragged her fingers up to my elbow, saying, almost to herself, “So soft.” My skin became the glass globe of a plasma ball as light from her fingertips flickered inside me. If there was any weed in my system, I was sure my racing heart would metabolize it in minutes. Desires, the existence of which I hadn’t admitted even to myself, coalesced into shapes that terrified me. I froze. If I’d giggled and feigned ticklishness, if I’d touched her the way she was touching me, I could have steered that night in a different direction.

I somehow noticed that before I heard the crash, although the latter must have caused the former. My awe transformed into a bone-deep terror. A man’s voice filled the air, carrying a rage so potent that I grabbed the window grate with both hands to steady myself. Everything he said echoed, and my chest tightened with every word he spoke.

In the green glass room, there are rabbits but no people.

Was I happy? Sometimes. I understood, at least, that my malaise would never be cured by a change of setting.

In the green glass room, you can fall but never land.

In the green glass room, there are beers and there are bottles.

For the period of time that I knew Mayra well, most of our conversations were electric, tinged with the ferocity of youth; our opinions were more than opinions, they were parts of our souls that we guarded like dogs, with raised hackles and widened eyes. But our conversation now was quiet, deliberate, adult. “Who am I, Ingrid?” she repeated in that infuriating indoor voice. I was used to the cadence and volume of speech in Hialeah, where, to an outsider, even friendly conversation seemed to edge near argument.

In the green glass room, it’s always summer, never winter.

It never occurred to me, in my childhood or my dreams, that the instinct to bolt when something huge and unfamiliar approached was a kind of wisdom.

Funny how quickly the body forgets pain, though when you’re in its grip, nothing exists but the present.