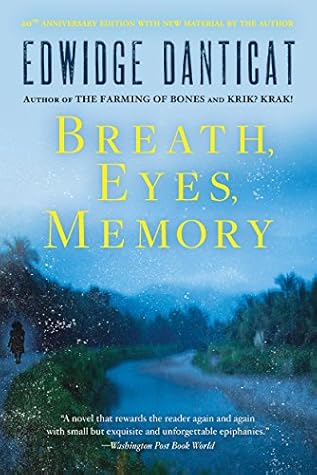

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Our men, they insist that their women are virgins and have...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Mothering. Boiling. Loving. Baking. Nursing. Frying. Healing. Washing. Ironing. Scrubbing. It wasn’t her fault, she said. Her ten fingers had been named for her even before she was born.

The air smelled like spices that I had not cooked with since I’d left my mother’s home two years before.

I usually ate random concoctions: frozen dinners, samples from global cookbooks, food that was easy to put together and brought me no pain. No memories of a past that at times was cherished and at others despised.

Tante Atie’s gentle voice blowing over a field of daffodils.

“It’s not love. It is duty.”

My mother paced the corridor most of the night. She walked into my room and tiptoed over to my bed. I crossed my legs tightly, already feeling my body shivering.

“Children are the rewards of life and you were my child.”

“You don’t seem to eat much,” she said. “After I got married, I found out that I had something called bulimia,” I said.

“You are blaming me for it,” I said. “That is part of the problem.”

Most of her messages were from Marc. His voice sounded softer than I remembered it. “T’es retourné?” Are you back? “Call me as soon as you get back.”

“It seems like ages. Does she still reach for people’s food?”

“I thought you would be hungry” she said, “on the road to recovery. How can you resist all this food?” “It’s not as simple as that.”

I’ll kill myself. Marc, he saves my life every night, but I am afraid he gave me this baby that’s going to take that life away.”

“The nightmares. I thought they would fade with age, but no, it’s like getting raped every night. I can’t keep this baby.”

“Because you don’t marry someone to escape something that’s inside your head. One night, I woke up and found myself choking Marc. This is before I knew I was pregnant. One day he’ll get tired of it and leave me.”

The sun shining through the window colored our wooden floors the hue of Haitian dirt.

“It’s nice to see you, but I want to kill you.” His free hand traveled up and down my blouse.

“You see I need you to put some order in my life,” he said. “You need a maid,” I said.

“You have never called it that since we’ve been together. Home has always been your mother’s house, that you could never go back to.”

“I do understand. You are usually reluctant to start, but after a while you give in. You seem to enjoy it.”

“If our skins touch,” he said, “I won’t be able to resist you.”

Joseph’s hands were creeping up my arm and going through the top of my nightgown.

I was lying there on that bed and my clothes were being peeled off my body, but really I was somewhere else. Finally,

“You were very good,” he said. “I kept my eyes closed so the tears wouldn’t slip out.”

I ate every scrap of the dinner leftovers, then went to the bathroom, locked the door, and purged all the food out of my body.

We thought it had floated into the clouds, even hoped that it had traveled to Africa, but there it was slowly dying in a tree right above my head.

“Non. She is rather in the morgue.”

“She stabbed her stomach with an old rusty knife. I counted, and they counted again in the hospital. Seventeen times.”

In her closet, everything was in some shade of red, her favorite color since she’d left Haiti.

It was too loud a color for a burial. I knew it. She would look like a Jezebel, hot-blooded Erzulie who feared no men, but rather made them her slaves, raped them, and killed them.

“She is going to Ginen,” I said, “or she is going to be a star. She’s going to be a butterfly or a lark in a tree. She’s going to be free.”

He looked frightened of the Macoutes, one of whom was sitting in Louise’s stand selling her

last colas.

I threw another handful for my daughter who was not there, but was part of this circle of women from whose gravestones our names had been chosen.

There is always a place where nightmares are passed on through generations like heirlooms. Where women like cardinal birds return to look at their own faces in stagnant bodies of water.

I come from a place where breath, eyes, and memory are one, a place from which you carry your past like the hair on your head.

My mother was like that woman who could never bleed and then could never stop bleeding, the one who gave in to her pain, to live as a butterfly. Yes, my mother was like me.

‘Ou libere?’ Are you free, my daughter?”