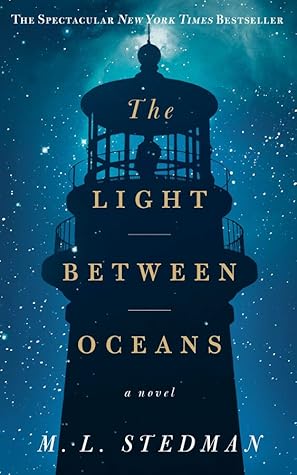

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Cathedral-high trees were felled with handsaws to create grazing pasture; scrawny roads were hewn inch by stubborn inch by pale-skinned fellows with teams of shire horses, as this land, which had never before been scarred by man, was excoriated and burned, mapped and measured and meted out to those willing to try their luck in a hemisphere which might bring them desperation, death, or fortune beyond their dreams.

Like the wheat fields where more grain is sown than can ripen, God seemed to sprinkle extra children about, and harvest them according to some indecipherable, divine calendar.

Gradually, lives wove together once again into a practical sort of fabric in which every thread crossed and recrossed the others through school and work and marriage, embroidering connections invisible to those not from the town.

And Janus Rock, linked only by the store boat four times a year, dangled off the edge of the cloth like a loose button that might easily plummet to Antarctica.

He slipped a book into his pocket and set out to explore the town.

It was the very heart of Janus, all light and clarity and silence.

something inside Tom was still for the first time in years.

You don’t think ahead in years or months: you think about this hour, and maybe the next. Anything else is speculation.

he was part of the unbroken chain of keepers bearing witness to the light.

All night, far above him the light stood guard, slicing the darkness like a sword.

Tom takes comfort from the orderliness of it. It is a luxury to do something that serves no practical purpose: the luxury of civilization.

“Your family’s never in your past. You carry it around with you everywhere.”

Splitting. Labeling. Seeking out otherness. Some things don’t change.

He weeps for the men snatched away to his left and right, when death had no appetite for him. He weeps for the men he killed.

Isabel is there in his thoughts, laughing in spite of it all, insatiably curious about the world around her, and game for anything.

It put things into perspective—the stars had been around since before there were people. They just kept shining, no matter what was going on. I think of the light here like that, like a splinter of a star that’s fallen to earth: it just shines, no matter what is happening. Summer, winter, storm, fine weather. People can rely on it.

Ralph spoke to the boat in the same way Whittnish referred to the light—living creatures, close to their hearts. The things a man could love, Tom thought. He fixed his eyes on the tower. Life would have changed utterly when he saw it again. He had a sudden pang: would Isabel love Janus as much as he did? Would she understand his world?

Even more, he was uneasy about parts bearing his name. Janus did not belong to him: he belonged to it, like he’d heard the natives thought of land. His job was just to take care of it.

Janus is where the word January comes from? It’s named after the same god as this island. He’s got two faces, back to back. Pretty ugly fellow.” “What’s he god of?” “Doorways. Always looking both ways, torn between two ways of seeing things. January looks forward to the new year and back to the old year. He sees past and future. And the island looks in the direction of two different oceans, down to the South Pole and up to the Equator.”

There are times when the ocean is not the ocean—not blue, not even water, but some violent explosion of energy and danger: ferocity on a scale only gods can summon. It hurls itself at the island, sending spray right over the top of the lighthouse, biting pieces off the cliff. And the sound is a roaring of a beast whose anger knows no limits. Those are the nights the light is needed most.

Like sparks flung off the furnace that is Australia, these beacons dot around it, flickering on and off, some of them only ever seen by a handful of living souls. But their isolation saves the whole continent from isolation—

The storms gradually follow winter to another corner of the earth, and summer comes, bearing a paler blue sky, a sharper gold sun.

how loss had leaked all over her mother’s life like a stain.

if a wife lost a husband, there was a whole new word to describe who she was: she was now a widow. A husband became a widower. But if a parent lost a child, there was no special label for their grief. They were still just a mother or a father, even if they no longer had a son or a daughter. That seemed odd. As to her own status, she wondered whether she was still technically a sister, now that her adored brothers had died.

The baby had healed so many lives: not only hers and Tom’s, but now the lives of these two people who had been so resigned to loss.

History is that which is agreed upon by mutual consent. That’s how life goes on—protected by the silence that anesthetizes shame.

He will come to terms with things, in the end. But a sliver of uncrossable distance has slipped between them: an invisible, wisp-thin no-man’s-land.

Words had a way of getting into all sorts of places they weren’t meant to. Best keep things to yourself in life, he’d learned.

Right and wrong can be like bloody snakes: so tangled up that you can’t tell which is which until you’ve shot ’em both, and then it’s too late.”

He thought, too, how his reflection in the mirror now offered glimpses of his own father’s face at his age. Likeness lies in wait.

The more she had access to words, the greater her ability to excavate the world around her, carving out the story of who she was.

A lighthouse is for others; powerless to illuminate the space closest to it.

plenty more fellows like me, trying to make the ships safe, keeping the light for whoever might need it, even though we’ll mostly never see them or know who they are.

Tom watches Isabel, waits for her to return his glance, longs for her to give him one of the old smiles that used to remind him of Janus Light—a fixed, reliable point in the world, which meant he was never lost. But the flame has gone out—her face seems uninhabited now. He measures the journey to shore in turns of the light.

A lighthouse warns of danger—tells people to keep their distance. She had mistaken it for a place of safety.

Dull aches of loss reawakened, as raw longing was soothed by that balm so long exhausted—hope.

There was nothing he was going through that the stars had not seen before, somewhere, some time on this earth. Given enough time, their memory would close over his life like healing a wound. All would be forgotten, all suffering erased.

We live with the decisions we make, Bill. That’s what bravery is. Standing by the consequences of your mistakes.”

“There’s nothing you can do,” her father had said. “Once a horse bolts, you can only say your prayers and hang on for all you’re worth. Can’t stop an animal that’s caught in a blind terror.”

Once a child gets into your heart, there’s no right or wrong about it. She’d known women give birth to children fathered by husbands they detested, or worse, men who’d forced themselves on them. And the woman had loved the child fiercely, all the while hating the brute who’d sired it. There’s no defending yourself from love for a baby, Violet knew too well.

He sighed, and looked up at a spiderweb in the corner of his cell, where a few flies hung like forlorn Christmas decorations.

“He gived me the forest,” said Grace, with the trace of a smile, and Hannah’s heart skipped.

When it comes to their kids, parents are all just instinct and hope. And fear. Rules and laws fly straight out the window.

The little girl responded by drawing pictures. Always the same pictures. Mamma and Dadda and Lulu at the lighthouse, its beam shining right to the edge of the page, driving away the darkness all around.

darkness seeps into the sky second by second, until the shadows no longer fall but rise from the ground and fill the air completely.

Humans withdraw to their homes, and surrender the night to the creatures that own it: the crickets, the owls, the snakes. A world that hasn’t changed for hundreds of thousands of years wakes up, and carries on as if the daylight and the humans and the changes to the landscape have been an illusion.

It occurs to him that there are different versions of himself to farewell—the abandoned eight-year-old; the delusional soldier who hovered somewhere in hell; the lightkeeper who dared to leave his heart undefended. Like Russian dolls, these lives sit within him.

“What have I done?” The question wasn’t rhetorical. She was searching for a mirror, something to show her what she could not see. “Can’t say that concerns me as much as what you’re going to do now.”

The rain transforms the living and the dead without preference.

How can you just get over these things, darling?” she had asked him. “You’ve had so much strife but you’re always happy. How do you do it?” “I choose to,” he said. “I can leave myself to rot in the past, spend my time hating people for what happened, like my father did, or I can forgive and forget.” “But it’s not that easy.” He smiled that Frank smile. “Oh, but my treasure, it is so much less exhausting. You only have to forgive once. To resent, you have to do it all day, every day. You have to keep remembering all the bad things.”