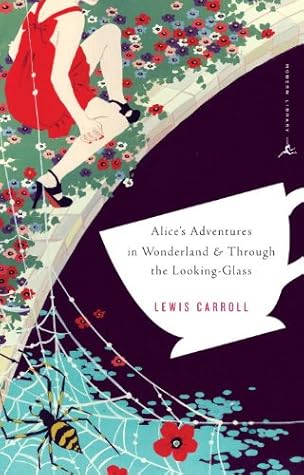

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Robert Graves’s poem praises the fictive Alice for her “uncommon sense,” being “of a speculative bent,” in accepting her adventures in her chance-discovered land as being

introduced the idea of the child as a new and growing mind in a strange world,

Franco Moretti claims that the English novel is childish because what is desired is not maturity and wisdom but a return to the safety and innocence of childhood—this is a half-truth, since there is never any illusion of happy innocence in the childhoods of Pip or Maggie or Jane.

What is most striking about the Alice books in this context is that they are not fairy tales. The wood is not the dark wood where the enchanter and the witch lurk. The creatures are not magical helpers or disguised princes. They are garrulous and argumentative philosophers and grammarians, and the world they inhabit is the world of nonsense, which exists only in contradistinction to the world of sense, common or uncommon, which Alice has in abundance.

It is her solidity that is magical. The wonders are not wild or strange but odd and curious.

one of the reasons for the successful creation of the Alice-world, I have come to think, is the almost complete absence of any object of love, attachment, or fear from Alice’s connections.

having problems with time and space and speed and distance, making, so to speak, local and provisional attempts to make sense of things. The

to realize how very different the world of Alice is. It is a world in which odd lessons are learned and odd rules are perceived, by trial and error, to exist—quite safely, because this is a world of nonsense.

The Field of Nonsense.

She generally gave herself very good advice (though she very seldom followed it), and sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. “But it’s no use now,” thought poor Alice, “to pretend to be two people! Why, there’s hardly enough of me left to make one respectable person!”

I wonder if I’ve been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is,

I’ll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn’t signify: let’s try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, that’s all wrong, I’m certain!

“Who are you?” said the Caterpillar. This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

Alice felt that this could not be denied, so she tried another question. “What sort of people live about here?” “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw round, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare.4 Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. “Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin,” thought Alice, “but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in all my life.”

“Your hair wants cutting,” said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech. “You should learn not to make personal remarks,” Alice said with some severity; “it’s very rude.”

“Why is a raven like a writing-desk?”

“Come, we shall have some fun now!” thought Alice. “I’m glad they’ve begun asking riddles,—I believe I can guess that,” she added aloud. “Do you mean that you think you can find out the answer to it?” said the March Hare. “Exactly so,” said Alice. “Then you should say what you mean,” the March Hare went on. “I do,” Alice hastily replied; “at least—at least I mean what I say—that’s the same thing, you know.” “Not the same thing a bit!” said the Hatter. “Why, you might just as well say that ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as ‘I eat what I see’!” “You might just as well say,” added the March

...more

Alice had been looking over his shoulder with some curiosity. “What a funny watch!” she remarked. “It tells the day of the month, and doesn’t tell what o’clock it is!” “Why should it?” muttered the Hatter. “Does your watch tell you what year it is?” “Of course not,” Alice replied very readily: “but that’s because it stays the same year for such a long time together.” “Which is just the case with mine,” said the Hatter. Alice felt dreadfully puzzled. The Hatter’s remark seemed to have no meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English. “I don’t quite understand,” she said as politely as she

...more

“Have you guessed the riddle yet?” the Hatter said, turning to Alice again. “No, I give it up,” Alice replied: “what’s the answer?” “I haven’t the slightest idea,” said the Hatter. “Nor I,” said the Hare. Alice sighed wearily. “I think you might do something better with the time,” she said, “than waste it asking riddles with no answers.” “If you knew Time as well as I do,” said the Hatter, “you wouldn’t talk about wasting it. It’s him.” “I don’t know what you mean,” said Alice. “Of course you don’t!” the Hatter said, tossing his head contemptuously. “I dare say you never even spoke to Time!”

...more